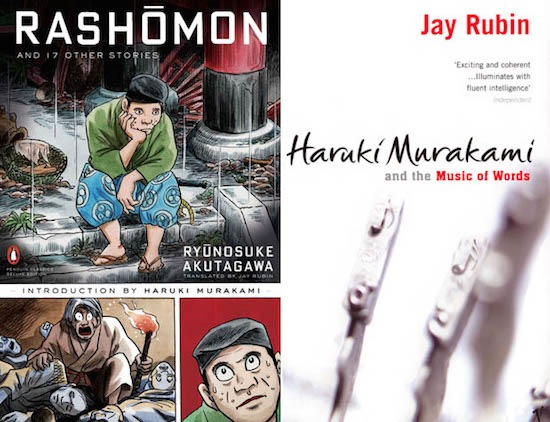

Jay Rubin’s translations include Haruki Murakami’s novels Norwegian Woods translations include Haruki Murakami’s novels Norwegian Wood, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, After Dark, 1Q84 (with Philip Gabriel), and a number of short story collections. Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, Rubin’s part-biography, part-analysis of Murakami’s work, was published in 2002 and updated in 2012. Rubin is also a translator of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (Rashomon and Seventeen Other Stories) and Natsume Sōseki (The Miner; Sanshiro). He holds a Ph.D. in Japanese literature from the University of Chicago. While teaching at Harvard in 2005, he helped bring Haruki Murakami to the university as an artist-in-residence.

***

Ryan Mihaly: I want to start by considering the role of the translator in today’s global society.

In Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words, you recount an incident where a re-translation of Murakami’s work into German (they translated English into German rather than the original Japanese to German) caused quite an uproar. One critic you cite accuses Murakami of supporting the “globalization” and “Hollywoodization” of his own work, effectively considering the Japanese versions as “mere regional editions.”

I think of a few other essays I’ve come across in my research—Eliot Weinberger pointing out that the translator is considered a “problematic necessity,” or John Ciardi, translator of Dante’s Divine Comedy, declaring translation “the art of failure.”

Can you think of a time when translation and translators have been looked upon favorably? What does it take to cast translation in a positive light?

Jay Rubin: Ha, interesting question. I’d like to know the answer to that myself. The German translations of Shakespeare are highly regarded as literature in their own right, I gather. And translators get a lot more respect in Japan than in the English sphere; there, readers choose authors by who has translated them. In general, I suspect translation is seen in a more positive light in less-than-dominant cultures that have to translate to keep up with the mainstream. American complacency keeps the incoming volume of translations low. Your question can only be answered by a wide-ranging multi-cultural survey. Good luck.

RM: Very interesting. I suppose this need to keep up with the mainstream is reflected in Murakami’s desire to be translated quickly.

What does it take, then, for a translator to gain respect in Japan? I wonder if they must be seen as good writers, first. Who are some of these respected translators?

JR: Murakami of course knows that he needs to be translated in order to be read widely. He is very conscious of the power of translation, being himself one of Japan’s most important translators of American literature. He has long collaborated with Motoyuki Shibata, a well-known professor of English literature at the University of Tokyo, who has his own flourishing career as a translator. Of course, both men are admired as great stylists in Japanese, and that attracts readers to the authors they choose to translate.

Murakami does his translation work in the afternoons, for relaxation, after doing his own writing in the morning. By now, he must have over 50 volumes of translated literature (see a sample in the bibliography of my Haruki Murakami and the Music of Words). Shibata recently retired his professorship to give himself more time to translate (Paul Auster, Stuart Dybek, Barry Yourgrau, Steven Millhauser, Thomas Pynchon [Mason and Dixon in 2 fat volumes!]).

In a development unthinkable in America, Shibata was the subject of a 150-page feature in a glossy magazine, complete with moody photos of the translator in evocative settings. Earlier, he and Murakami were subjected to a more academic book-length study demonstrating how their translating had influenced literary style in general in Japan.

RM: Amazing—Shibata sounds almost like a celebrity. And to think of translation as a form of relaxation… for a writer as disciplined and prolific as Murakami, this makes sense, almost like a literary cool-down lap. But I still feel the idea of translation as relaxation, and as a subject of a 150-page spread in a magazine, are both views contrary to popular ideas of translation in America.

I want to shift to your work translating Murakami. His novels in English have only appeared in commercial editions, where you do not see footnotes describing words that are difficult to translate or certain cultural items from Japan that deserve an explanation. Though the publishers probably demand an absence of such notes, do you ever feel his work would benefit from them? Have restrictions such as these imposed by the publisher made translating him more difficult?

Also, now I must ask—is translation relaxing for you?

JR: Part of the fun of translating in a commercial edition is sneaking in explanations and clarifications without resorting to footnotes or other overt devices. I’ve never had a situation translating Murakami in which I wanted to use a footnote. I want the reader of the translation to have the same literary experience as the reader of the original, not to be distanced from it by running commentary. So, no, I don’t think Murakami’s work—or that of any contemporary writer—would benefit from notes. My translations of modern classics by Sōseki or Akutagawa, though, are full of notes.

I enjoy the challenge of trying to recreate in my native language what I have experienced in reading the original. That takes a lot of concentration, and my brain usually turns to mush after three or four hours in the morning. Unlike Murakami, I don’t get a second wind in the afternoon, and it’s downright cruel of him to suggest that what I do as work he does for fun. I relax by getting out of the house and walking.

RM: Though it may be hard to imagine now, do you think the future translators of Murakami, say, at the end of this century, will be required to fill their translations with notes?

Or, to consider this question from another angle—at what rate are new Japanese words and phrases making their way into English, if at all? As cultures in America and Japan continue to grow and change, what is managing to reach across national boundaries; what is managing to shape English-language readers’ idea of Japan? And how does translation contribute to this cultural exchange?

JR: One of the things that attracted me most to Japanese language, literature, and culture was the fact that nobody else was doing it. Over the years, I have watched with increasing dismay as sushi made it first to the cover of The New Yorker and then to every town in the country. Now you can buy panko at any supermarket, and foodies talk about umami without further explanation. What’s the point of working on Japan anymore?

RM: The contemporary Japanese writer Takashi Hiraide’s novel The Guest Cat just made it to the New York Times bestseller list—the first ever to make that list from New Directions. Not to mention the rise in popularity of other Japanese authors like Yōko Ogawa. In other words, people are still translating new Japanese writers and people are reading them.

RM: Yes, Murakami has really opened the way for other Japanese writers. It’s pretty amazing. I had very little sense of how famous Murakami was in Japan when I first started translating him. I just felt he was writing for me. Over the years, the most consistent note in the feedback I’ve gotten from readers has been exactly that: he is writing for me. Probably all great writers accomplish that, though I’m not sure how.

RM: In an essay describing his process of translating The Great Gatsby into English, Murakami said people would often ask him how he would translate Gatsby’s endearing term “old sport.” He ended up keeping it exactly as it is. What are some Japanese terms or idioms, whether in Murakami, Sōseki, Akutagawa, or others, you have found challenging to translate?

JR: Probably the most challenging terms are the most common ones. Most Americans know about the suffix -san that follows Japanese names, but fewer know about the related suffixes that show graded levels of respect, -sama being highly respectful, -kun being far more familiar, and nothing following a name being so lacking in respect that the absence of a suffix can be taken as an insult.

Much of the humor in Murakami’s wonderful [short story] “Super-Frog Saves Tokyo” hinges on these suffixes as the protagonist, overawed by the six-foot frog he finds waiting for him in his apartment, tries respectfully to call him “Frog-san” while the frog himself insists on being called “Frog-kun.” I racked my brain trying to think of a way to convey the comedy without resorting to footnotes, and finally came up with a simple solution that gave me a lot of satisfaction. The frog tells the human protagonist, “Call me ‘Frog,’” with a capital F as if it were a name (vaguely reminiscent of “Call me ‘Ishmael”), and whenever the protagonist tries to be respectful in English, he calls him “Mr. Frog.” I wasn’t sure it worked until I attended the stage adaptation of the story and heard the audience laugh whenever the frog said, correcting him with one finger raised, “Call me ‘Frog.’”

RM: Who from Japan—contemporary or from previous eras—do you hope to see translated into English?

JR: I’ve been working on an anthology of modern Japanese short stories for Penguin, which will have new works by such icons as Jun’ichirō Tanizaki and Kafū Nagai and some stories by upcoming writers Yuten Nishizawa, Yuya Sato and Tomoyuki Hoshino (who had a wonderful story in the recent Japan issue of Granta).

RM: Finally, you’ve spoken elsewhere of the differences in yours, Phillip Gabriel’s, and Alfred Birnbaum’s translations of Murakami. Do you think having several translators of a contemporary writer enhances or complicates our understanding of them?

JR: Of course it complicates our understanding of the writer, but it also helps to make the reader more aware of the provisional nature of translation.

***

Ryan Mihaly is the project coordinator for Words in Transit: The Cultures of Translation, a year-long festival of translation at Amherst College. He has written for Biblioklept and Flying Object. See his website here.

Read more: