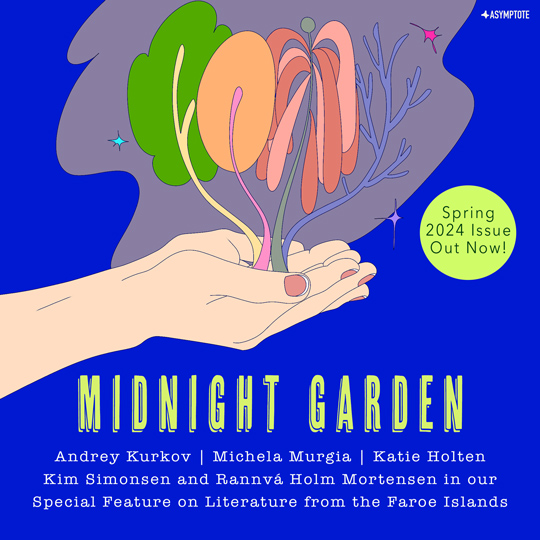

When we fall asleep, where do we go? Why, of course, to a #midnightgarden‚ filled with exciting discoveries from 32 countries, including interviews with Andrey Kurkov and Diamela Eltit, fiction by Michela Murgia and Khrystia Vengryniuk, apocalyptic drama from Honduras, new translations of Alfred Döblin and Ludovico Ariosto—specifically, of his Orlando Furioso, the bestselling book of the sixteenth century—as well as a Special Feature on Literature from the Faroe Islands, sponsored by FarLit and headlined by Kim Simonsen and Rannvá Holm Mortensen. Ahead of the 60th Venice Biennale opening this weekend, we are proud to unveil our own international showcase—illustrated with elan by Korean guest artist Joon Yoon—still the most ambitious of any literary periodical.

Among the highlights in this edition is visual artist Katie Holten—herself a veteran of the Venice Biennale—who returns to our pages to discuss her rustling, arresting Language of Trees, a response to ecological catastrophe. Michelle Chan Schmidt reviews a similar attempt to capture new language, crisis language, when extremes brought about by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine called for A Dictionary of Emotions in a Time of War. Interviewing young Somali refugees for a dictionary entry, “Partire” or leave, Somali-Italian writer Ubah Cristina Ali Farah discovers how disasters—in this case, civil war and genocide—“reveal the limit of language.” In Fiction, a “great flood” forms the backdrop of Khrystia Vengryniuk’s mordantly funny but ultimately heartbreaking story about two star-crossed lovers. By contrast, LGBTQ+ rights activist Michela Murgia’s relatively uneventful piece centers a soon-to-be empty nester and the solution to her ennui that she tucks away in her wardrobe: a life-sized cutout of BTS boyband member Park Jimin.

Just this past week, the Financial Times reported that “rising nationalism and falling funding is reshaping the Venice Biennale;” at Asymptote, we find ourselves running up against the same constraints that keep the art world from fully realizing its potential (as a matter of fact, just carrying on remains a challenge because we are incorporated outside of the US and Europe, where most of literary arts funding lies). If you have benefitted from our work these past thirteen years, consider helping us grow this #midnightgarden as a sustaining or masthead member. Together, we can keep it alive.