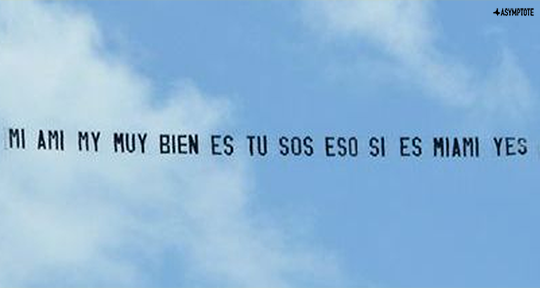

The O, Miami Poetry Festival is a month-long celebration of verse in Florida’s capital, with the mission of establishing a series of events, performances, and public exhibitions, so that “every single person in Miami-Dade County [can] encounter a poem.” The festival’s programming included a translation workshop held by Layla Benitez-James and Jorge Vessel, consisting of two intensive sessions dedicated to studying, discussing, and building upon the complex art of poetry translation. In the following dispatch, Benitez-James gives us a behind-the-scenes look at the going-ons of the workshop, and presents the fruits of the translators’ labour: a poem by Colombian poet María Gómez Lara.

At the end of April, across two continents and various time zones, a group of translators met virtually to discuss, translate, and workshop the poem “palabras piel” by Colombian poet María Gómez Lara. Organized by O, Miami in partnership with the Unamuno Author Series (UAS), the creative task was set as part of a translation workshop lead by two members of the UAS team: award-winning Venezuelan writer, translator, and engineer, Jorge Vessel (pseudonym for Jorge Garcia) and myself, a writer and recent winner of an NEA in translation. Over two sessions in consecutive weekends, we discussed translation theory, inspiration, and collaborated on a wonderfully challenging poem.

The translation workshop was hosted by O, Miami Poetry Festival Founder and Executive & Artistic Director P. Scott Cunningham, who took part in the inaugural Unamuno Poetry Festival in Madrid—the city’s very first anglophone literary festival (Scott’s poem “Miami” from his collection Ya Te Veo was translated into Spanish by Jorge for The Unamuno Author Series Festival Anthology). While the aim of the O, Miami festival is to help each and every person in Miami encounter a poem throughout the month of April, our personal goal in 2019 was to introduce over eighty poets and academics to Madrid’s literary community; as such, translation between Spanish and English has become an important part of both organizations.

Our objective for the workshop was to inspire and embolden participants to take up a translation project of their own, as well as to broaden their ideas of what those projects might entail. While we would open up a discussion about basic elements of translation, we also wanted to expand upon how these writers and translators thought about the overlaps and symbiosis of their creative processes—how the act of translation itself can be the spark or jumping-off point for inspiration. READ MORE…