This month, our editors dive into two powerful works that look into the dominating subjects of human life: sex and war. An erotically subversive collection of stories by award-winning author Mónica Lavín moves to the darkest and most questioning arenas of desire, and a memoir by Algerian Freedom fighter Mokhtar Mokhtefi stands as a cogent and compelling text of witness of his nation’s struggle against French colonialism.

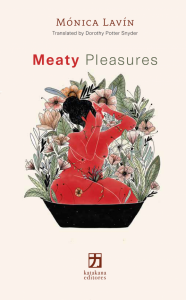

Meaty Pleasures by Mónica Lavín, translated from the Spanish by Dorothy Potter Snyder, Katakana Editores, 2021

Review by Lindsay Semel, Assistant Managing Editor

There is catharsis in transgression, and pleasure—especially the centering of one’s own pleasure—is all too often transgressive. The twelve short stories in Mónica Lavín’s collection, Meaty Pleasures, thoughtfully curated and translated by Dorothy Potter Snyder, capitalizes on this subversive desire, exploding the tranquil veneer of domestic life by compelling our complicity in the deeply uncomfortable and socially taboo.

It all begins and ends with the flesh. “Postprandial,” the decadent opening story, foregoes grounding details about setting and character in order to focalize an aphrodisiac tasting menu, offered from a hotel restaurant manager to a passerby, and the explicit sex that follows. It readies the reader for Lavín’s challenging approach to realism, intimacy, and power imbalance which pervades the rest of the collection. The final story, “Meaty Pleasures,” also emphasizes the sensual relationship between food and sex—but in a completely different way. Told from the perspective of an adult daughter who has watched her parents’ Saturday afternoon artisanal butchering hobby grow into an obsession that echoes over the course of their lives, the sex is left entirely to the implicit, straining in constant tension with the parental web of familial obligations. The daughter and her sister reflect: “Sometimes we’d ask each other, have you tried calling Papá and Mamá on Saturday afternoons? Because on that day of week, they never answered the phone to either one of us.”

In between, we meet many a troubled family. As is common in stories of nonconformity, various characters rebel against the numbing effect of matrimony, but their resistance does not lead them to any predictable conclusion—or perhaps any predictability is heightened to a manic extreme. In “What’s there to come back to,” a husband leaves his repentant wife on their doorstep for a whole winter’s night before he, begrudgingly, allows her back into their home. Snyder’s translation captures a certain languor and resentment in his stream of consciousness that induces anxiety when set against the excruciating awareness of her waiting, building a rawness that painfully and coldly leads to his reflection upon waking up in the morning: “Fried eggs again for breakfast, the TV news. I think she’s gone. Maybe she froze to death. Maybe we both froze to death.” In “You Never Know,” a son tires of the demons left to him by his mother’s abandonment. “Then, you kiss and hug them in the shadows of a movie theater, and you masturbate thinking about them, and when you start to want something more than their bodies, like their companionship and tenderness, you leave without saying goodbye.” Innocent—righteous, even—though his anger seems, his journey darkens with an incestual turn. “Roberto’s Mouth” finds a disgruntled housewife disappointed yet again when her own plans to leave her family are thwarted by her naughty-mouthed chat-room lover’s lazy approach to cuckholding. In such narratives that continually unpack and distort the concepts of familial intimacy, images of transgressively penetrated flesh dominate the collection, inviting the reader to reflect on the discomfort they inspire. READ MORE…