That day, some pregnant women had been among the saved. How many mothers had lost their children during their journey? How many hadn’t made it? We know nothing of them and of the crosses that they bear, and we don’t know whether the fault is ours: it is and it isn’t.

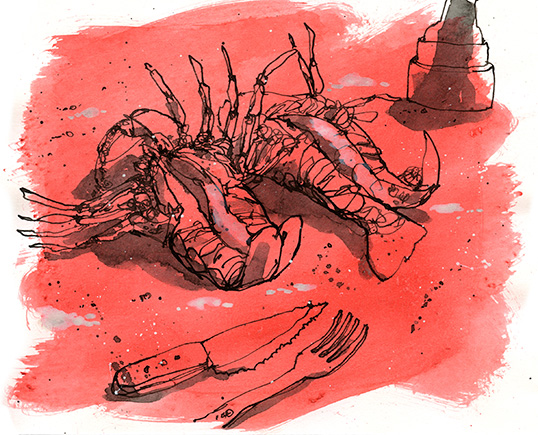

The karavida has an ancient shell, with symmetrical spikes. If you split it in two it looks like two little boats or two halves of a nut, two keels whose tiny zigzag borders can be perfectly reunited. We extract the meat with surgical precision. We enter between the edges and the flesh, which we try to break off while ensuring that at least the main piece keeps its shape. We snap off its claws and suck them dry. The eyes of a karavida after it has been boiled are dark green, unlike its eyes when it is alive in the sea, and they are as hard as little pebbles. A live karavida differs from a lobster in that it is grayish. The antennae of a cooked lobster are often broken off, and they are much longer than a karavida’s; sometimes the karavida is served with one antenna still intact, in accordance with some archaic aesthetic code. During both our karavida dinners and our lobster dinners we discuss the events of the day in an imprecise and scattered manner: the small, the minute, the private, the bourgeois, the precarious, the public, the political, the economic, the worldwide, the universal, the twentieth-century. We read about them in La Repubblica, in Corriere della Sera, in Le Scienze, in Internazionale, online (X posted about . . . ), in the New Yorker, on WhatsApp.

That evening with the karavida, someone was talking about economic refugees and political refugees; someone connected to the WiFi and read various inhumane comments and tweets aloud, who said what to Salvini and Saviano; and then we talked about NGOs and Operation Triton, about how we can’t go on like this. We were often silent, uttering those series of words that function as linking phrases: it’s all just so unmanageable, it can’t be legislated, there’s too much true and untrue information to process, too much daily exhaustion, yearly exhaustion, so pass me the fries, the tzatziki, pass me the oil, lemon, salt. In the end, we know how to talk about tzatziki and garlic. We don’t know how to talk about anything else. We don’t want to know.

The karavida, also known as the cicada of the sea, has an incredibly hard shell that is, nevertheless, very thin. Here’s how it happened: the year before we had been by ourselves. The others were in the village and we watched them from afar, from above, between the shrunken white houses. We walked among the olive trees and pointed out the boat docking at the harbor.

We stopped at the Orthodox church; we entered and lit a candle and incense. We went outside; it was windy, and we sat down for a while. Then we decided to go up to the lighthouse. We walked past the vegetable gardens and followed a path through the dry grass, without speaking. We continued along a winding, uphill course, and we were both aware and unaware of what we wanted to do. We reached the plateau, which looked like a dry yellow desert, and stood there in silence with flies and grasshoppers gathering around our feet. Staring out at the overhang, we asked ourselves: What would it feel like to jump?, and we drew nearer to the edge. We returned to surer footing and slid down a steep, nearly unbeaten trail on our asses, repeating to ourselves: What if we jumped?—and imagining the dead weight of our bodies in flight, the haphazard, violent slap against the water. Then we reached the pebble beach, and the sun had already almost set. Maybe we weren’t at the beach yet; maybe it happened later, when we got home, as the wind whipped against the shutters and we asked ourselves what if we . . . Maybe it really happened: we drew nearer to one another, we let our hands slide over each other’s bodies as we repeated the same gesture over and over—as we began to do those things of which we’re all aware.

We were, in fact, surrounded. We knew about our friend Anna, and Francesca’s pregnancy, and how Federica was trying. We were aware, thanks to all the flyers, that we could freeze our eggs for when our time came. We were aware of our friends’ advice: you have to go for it, now or never. The government had explained this to us through the #fertilityday campaign: beauty is ageless, fertility isn’t. We were aware of HCG levels and early pregnancy tests. But we were also aware of Gianna Nannini giving birth at the age of fifty-five. We were aware of short-term contracts, temp jobs, the precariat, and we were aware of the postwar baby boom. We were aware that, no matter what happens, you’re still a woman, remember that. We were also aware that sometimes children served as consolation prizes. In the same token, they explained to us how those little automatic cribs rock newborns, and now we know for certain that Clio is pregnant, and soon we’ll be able to follow Chiara’s pregnancy on Instagram.

As a child you aren’t aware of how it works: first, the glandular epithelium, the mucous membrane, starts to shed (have you sinned greatly? how have you sinned? what have you touched?). Then a few drops descend, maybe at night in the dark, horizontally; they overflow like grief. The inside is cleaning itself: everything is being made anew, although, on the outside, everything is soiled. You get up, you crouch down, you rinse yourself off (Forgive, O Lord, for Thy dear Son, the ill that I this day have done), you gather water with the concavity of your cupped hand and you bring it to your concavity, and the water turns pink or red. You rinse some more and it seems to have tapered off, but not for long. The first few times it’s a mystery (I firmly intend, with Your help, to do penance, to sin no more, and to avoid whatever leads me to sin). Then you learn how it’s done: you adjust yourself to avoid stains, you create a technique that you’ll use for years, a ritual. You learn the length of those days, your cycle (live life, stay free—because comfort counts).

If you’re twelve years old, about five hundred to seven hundred cycles await you. That dusk on the pebble beach, when the sun has already almost set, is the exception (ten Hail Marys and an Our Father): at that point, four hundred million undulant entities climb inside you, their tails oscillating and pushing through the fluids; at that point, one rises, enters, creates (because of course we know we need a seed to make a tree). First of all, these entities contain DNA (thud of a carpenter’s hammer). They move through the canal to the beat of Delibes’ Flower Duet; at 00:54 the strongest specimens rise to the cervix, slowing down as they wedge themselves into its crevices; at 01:15 they’re in the fallopian tubes; the ones that remain spread out, stop, disintegrate; at 01:36 one finds the ovum (follicles, estradiol, corpus luteum, progesterone), latches on, and fuses to it. Then the ovum descends into the uterus; it rests there, implants itself.

This all happens inside, while outside there’s no sign of it. Can we call all this the Lord’s work? In the meantime, we praise the fruit of the egg’s labor, the mechanics of uterine movements, the precision of cellular reproduction, the power of the double helix, and praise be to molecular biology (“it is like a mustard seed. It is the smallest of all seeds, which, when it falls on cultivated soil, produces a large branch and becomes a shelter for the birds in the sky”).

We were saying that the karavida, also known as Scyllarides latus, has a very strong shell. It reproduces in the spring, protecting its eggs beneath its abdomen. They told us to wait three months, but that still-invisible thing felt alive. We then discovered that we knew nothing; and while we were celebrating on the outside, a primordial battle was taking place on the inside.

Artwork by Emmanuela Carbé

We discovered that our grief is simply called a “hiccup.” We are now aware that it happens often. Google then hands you over to the forums of the non-mothers who are trying to become mothers: some have been unsuccessful many times, others have only made a few attempts.

Before reaching this place, we tried the more scientific routes of Google Scholar and Google Books, then Google Images, and finally here. We had already been aware, for years, of groups named things like “Young Moms Forum” and “Teen Moms & Baby Bumps,” because many of our friends would screenshot their comments and offer them up for the general amusement of the public, and we were also aware of the pictures of tiny babies in the temporary custody of Facebook Inc. This was yet another planet, as indecipherable as the others, and we began to track its movements. In these dark, heart-filled places, the avatars know they can confess. They can count the days together and communicate in the tribe’s ciphered code, comprehensible only to the initiated: CD, BFP, OPK, DPO, fertile window, TOM, phantom symptoms, stims, TTC, crossing my fingers that I won’t get my period on January 20th!, who else is trying to get pregnant by September?, wishful thinking, but does this look positive? They take apart the tests, they analyze them and photograph them; they ask: Is there any hope? The discussion threads are long, but almost all of them cut off abruptly. When the thread is abandoned it means that something went wrong. Each thread carries its own cross and we can’t judge, because we don’t know anything about them.

We are unaware of everything on every scale. What do we know about mothers who have been raped, or those who live in neonatal intensive care units? What do we know about those who lost their children in terrorist attacks, the mothers of September 11, the mothers of the jumpers (the women too—the tumbling woman; do we know how to remember the women?)?

We don’t know about Bozaina Mohamed Mustafa Sheraqi, mother of Atta (US conspiracy; my son is alive in Guantanamo) and the mother of Youssef Zaghba (pass me the tzatziki, pass me the salt). We don’t know about the mothers of the two thieves on the cross, Titus and Dismas or Dysmas Dimachus Dumachus, Demas and Gestas (also known as Zoatham), and Camma or Chammata, or Joathas and Maggratas. We should know everything about the Virgin Mary, Mother of God, but we know even less; we don’t know about her missing menses, her happiness or terror, her being chosen, the pain, the way her blood sped up; we are aware of her hand, curved in protection, and we are aware of it thanks to Piero della Francesca’s Annunciation (c. 1455–1465). Here, Mary does not hold a book. She leans back, one hand holding her side; she’s tired, her vestment is partly undone, and her face is tense and serious. Maybe she feels Him kick (or perhaps He didn’t kick?). Maybe she suffered during labor. Praise be to the mother who mourns her son, the mother of the terrorist and the mother of the kamikaze, the mother who was unable to become a mother, the mother who didn’t want to become a mother. Praise be to all of them, because we don’t know anything about them.

And praise be to our Maria, a widow, who lost a son seven years ago when he died on a nearby island where they kept their goats and vineyards. Alone out there, without cell service, he had cut his wrist with a chainsaw; he had then tried to return home and a fishing boat had found him at sea with a T-shirt wrapped tightly around his wrist, a keel full of blood and a stopped motor. At the dock, the women tore their hair out, wailing. Maria is now ageless and absent. She smiles, she bakes bread, she sits outside by the front door. On Sundays she goes to church. She hides her two gray braids under her black headscarf. Maria rents her rooms out for the summer; she doesn’t know English. I stepped into her kitchen to give her the month’s rent. She speaks to me in Greek; I nod and answer in Italian, and we try to understand each other through gestures. She offered me some grapes. I told her, fish tonight: Kostas’s son caught some kalamares, and she said ai, kalamares. We talked about the events of the week, or at least I think we did: about the wedding that took place in town, the earthquake no one felt, the migrants who reached the nearby island, and that bread that I liked so much. I showed her where Egypt was on Google Maps and she was shocked; I think she said ai, is Syria really so close? This year she asked me again whether I have children, and I shook my head no, and she said ai diskola, ai diskola, and I smiled, stretching out my hands. I told her yes, Maria, and I held her hands in mine, truly alone.

The karavida, the cicada of the seas, has an ancient shell. I observe its symmetrical perfection and it amazes me. I’ve given myself the task of extracting as much of the meat as I can and bearing it across from one plate to another. In the meantime, pass the fries, tzatziki, oil, lemon, salt. At the end of the dinner I take the two parts of the shell and try to scrape off the last bits still attached to it. I jab the knife into it. I want it completely emptied, clean. I try to put it back together in one piece; I hold it vertically and touch the protective fragments that surround its two front fangs. I play with the joints of its claws; I raise and lower them like a warmup stretch. I crack one claw open to observe the inside of the joints, which are little spheres, and I hurt myself. I slowly press down with my fingers. I touch its eyes; I take one out of its socket and try to crush it, but it’s too hard, so I roll it around with my index finger instead. I’ve been to Ellis Island too, I tell the others, hiding the eye under my napkin. We order some raki. I go to the bathroom to wash my hands and I am ashamed of myself.

The night ANEK Lines ferry, with its little lights, is approaching the port. Every time it passes, we get up from our tables to take a closer look. The Greeks comment on its maneuvers: this year there’s a new captain, and last week he couldn’t reach the dock in the high winds. The ANEK Lines ferry is full of grace, despite the tons of weight it carries. It moves and turns on itself, challenging the waves without faltering. It berths, using two cables to tie itself to the limited space on the jetty. When the ship is securely fastened to the shore and the walkway has finished its creaking descent, small shadows of men and cars exit in single file. Of course it happens: slipping your hand in his, repeating an affectionate, unchanging gesture, without knowing why. Drawing near to his face, forgetting once again that we know nothing of that primordial battle.