“And the tongue is a fire, a world of iniquity . . . [that] setteth on fire the course of nature.”

(New Testament, James 3:5-6)

In the symbolic realm, the tongue holds a particular significance. This mobile, muscular organ is the only internal one we have that protrudes outside the body, and it can therefore be associated, quite viscerally, with the expression of what is within. It is a means by which we give voice to thoughts, feelings, truths and lies—an ultrasensitive interface with the outer world. The line from the New Testament, “the tongue is a fire”, captures the essentially double-edged nature of this organ of speech. Language, like fire, can comfort, warm, kindle, ignite the passions. It can also curse, kill, catch and raze nations to the ground. The tongue is a fire, in the most symbolic sense, as it is both creator and destroyer. It has the power to make and unmake worlds.

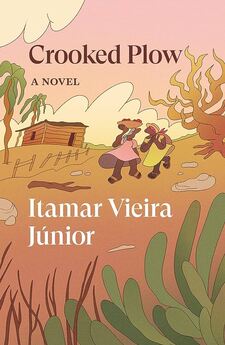

In the opening pages of the novel Crooked Plow by the Brazilian author Itamar Vieira Junior, translated into English by Johnny Lorenz, we meet two young sisters as they stare at a mysterious knife with an ivory handle, hidden under their grandmother’s bed. Bewitched by the gleam of the polished silver metal, the desire to taste the blade overwhelms them. A tussle ensues, leading to tragedy: “along with the lingering taste of metal came the flavour of the hot blood that began to run from a corner of my half-opened lips.” One of the girls leaves the encounter holding her severed tongue in her hand.

This fairytale-like act of violence kickstarts a novel that is ambitious in its intensity and historical impact. It is set around the floodplains of the fictional Água Negra, a narrow strip of plantation land in the northeastern region of Bahia (the author’s birthplace) occupied by subsistence farmers and owned by the shadowy, faceless Peixoto family, who have never worked the land themselves but reap the profits from their tenants’ unpaid labour. The two sisters, Bibiana and Belonísia, belong to this farming community descended from Afro-Brazilian slaves. Brazil was the last country in the world to abolish transatlantic slave trading, in 1888. After the abolition, the exploitation of former slaves continued under another name: they became “tenants” working on these vast plantations. As the novel indicates, the country has largely failed to reckon with this aspect of its colonial past, whose spectre continues to haunt every corner of Brazilian society. In Vieira Junior’s Água Negra the authorities routinely turn a blind eye to the exploitation of these communities by landowners, and the crimes perpetrated against those who speak out are buried both physically, in the earth itself, and figuratively, under tortuous bureaucracy.

As Belonísia, now mute, and Bibiana, who acts as a voice for both sisters, grow into young women, they remain fatally bound together by the ivory-handled knife. Deep in the Bahian hinterland, theirs is a world of famine and exploitation, power and terrible violence, where they learn to till and nurture the land, collecting buriti fruit with its thick orange pulp to sell at market, and navigating competing forces of duty and desire. A cast of characters emerges around them. Grandma Donana and her suitcase full of secrets. Their eloquent cousin Severo, who plants the seed of an idea to escape the plantation. The identical twins who live nearby, Crispina and Crispiniana, whose jealousy over a man drives them both to madness. Their father, the healer Zeca Chapéu Grande, who presides over the rituals of Jarê, the local Afro-Brazilian religion, and holds the fabric of the community together.

“Suffering was the secret blood running through the veins of Água Negra”. The inhabitants are effectively chained to the land, without rights, prohibited from building homes out of any material but mud, at the mercy of terrible droughts, floods and poor harvests. “The way the system operated, it was the workers who were indebted to the owners of the land, for having been granted the opportunity to work; except for that debt, they had nothing to bequeath to their children and grandchildren”. This “debt” is passed down the generations—one of many transgenerational traumas—along with a deep communion with the soil they work. “Whenever he encountered some problem in the fields, my father would lie on the ground, his ear attuned to what was deep in the earth [ . . .] like a doctor listening to a heartbeat”. It is a globally familiar injustice that the tenant farmers of the Fazenda Água Negra have a relationship with the land that is infinitely more intimate and entwined than the people who own the land and profit from it.

In the international popular imagination, Brazil is synonymous with its famous megacities. But it is these swaths of rural land, and the disputes that rage over land ownership, which have shaped much of the nation’s history. The political voicelessness of these communities, descended from fugitive slaves living in settlements known as quilombos, finds an overt resonance in Belonísia’s muteness. She writes: “my voice was a crooked plow, deformed, penetrating the soil only to leave it infertile, ravaged, destroyed”. This link between having land and having a voice is given a gendered inflection here, too. It is Belonísia whose short-lived marriage to the drunk, verbally abusive Tobias is characteristic of the lives of many women in these rural areas of Brazil, where they are vulnerable to being preyed upon and abused by angry, desperate men “hitting them till their blood, or their very lives, poured out, leaving a trail of hatred on their bodies [ . . .] introducing us to the hell that so often is a woman’s life”. Belonísia, mute herself, embodies the suffering of so many other voiceless women.

Translation, of course, is also all about the voice. The migration from one foreign tongue to another is where all kinds of worlds collide. In Lorenz’s crystalline English translation, Crooked Plow commits to the sparse, folkloric tone of the original Portuguese, coupled with a keen attention to the nuances of narrative voice, which is disrupted by Vieira Junior. The narrative of the novel is fragmented and multi-angular, first told through the voice of Bibiana, then Belonísia, and lastly by one of the Jarê spirits, who takes possession of the bodies of various characters, acting as an apparently omnipotent narrator. As the injustices on the plantation mount, the bodies pile up and tensions simmer between the activist Severo and the landowner Salomão; there is the weight of violence and bloodshed in the air. In the novel’s final act, a retribution of sorts is carried out, orchestrated by all three female narrators, involving the fateful knife with the ivory handle and a deep pit dug out of the earth. As the Jarê spirit says, ominously, “the land itself can be a trap”.

There are many figures of women without a tongue throughout literary history. Perhaps the most famous in the West can be found in the Greek myth of Philomela, told in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Philomela is raped by Tereus, who cuts out her tongue to prevent her from revealing his crime. But she thwarts his attempt to silence her by weaving a visual account of the story into an intricate tapestry, effectively denouncing him through the medium of art. This early commentary on censorship, on the silencing of women, and on the role art can play in revealing important or inconvenient truths about those in power, all find echoes in Crooked Plow—which is itself a work of art that has already made a seismic impact on the Brazilian literary landscape since its publication in 2018. In Itamar Vieira Junior’s novel, the same blade that takes Belonísia’s voice becomes a weapon of vengeance to redress various evils in the exploitation of Afro-Brazilian people, its double-edged nature revealed at last.

Ultimately, it is the tongue that serves as both the “crooked plow” of Vieira Junior’s title and the organ that determines the trajectory of both sisters’ lives. Bibiana, having used her voice to make up for her sister’s, later becomes a teacher turned activist, and by the end of the novel she comes to act as a voice for the whole community of Água Negra. In an encounter with the authorities, “she declared she was a quilombola. They responded by telling her there were no quilombos in that region”. But her tongue becomes a fire that catches: “Other voices, voices of people who’d always kept mum [ . . .] started joining in”. The community is voiceless no longer. Belonísia, on the other hand, embodies “the fury that had travelled through time”, the silent rage and suffering of a people “who had been wrested from their land, who’d crossed an ocean, who’d left their dreams behind and forged in exile a life that was new and luminous”. Crooked Plow is a novel that shows us, through magic and murder, how the tongue can also be a fire in the greatest sense—one that can alter lives, spark movements and claim freedoms.