I’m curious about your research process. Some of your works feature realistic depictions of actual spaces, altered in ways that range from subtle to drastic, and other times your work depicts spaces which are themselves assemblages you’ve created by combining multiple locations, imaginary spaces, and other artworks. In terms of painting in response to other paintings, to churches or subway stations: Do you actively seek out these references, or capture them as they strike you? Also, your work sometimes seems to collapse time, referencing colonial Brazil while also speaking to contemporary issues. Could you describe your process, how you might find inspiration for a piece and develop the pictorial and conceptual layers from idea to finished work?

The main subject of my artistic practice is religion and how it has been used as a tool of control throughout history. The field of research is vast, allowing me to combine images of Byzantine frescoes with pastors from contemporary Charismatic churches in Brazil within the same painting.

My search for such references is often predetermined, such as my research in 2018 at the Santa Casa de Misericordia Hospital in Rio de Janeiro, an institution founded in the sixteenth century and one of the places where information on the history of Brazil is preserved, or my more recent research on the beginnings of Christianity in Rome and the works of great masters like Giotto, Fra Angelico, and Piero della Francesca.

A painting begins from the power of a particular reference—an architectural space, a decorative element, or a historical painting—and the narratives are constructed through the layering of images that can also result in imaginary or modified spaces. The purpose of this combination of images is to compare and confront social structures, the changes or stagnations that religion has driven through time.

The Providers’ Room, 2018, oil and acrylic on canvas, (194x290 cm).

I was struck by a resonance with your painting Farm Management Instructions 2 when I read the following from Brazilian novelist Itamar Vieira Júnior’s Crooked Plow (trans. Johnny Lorenz), in the descriptions of a house in mid-twentieth-century Bahia:It was like a decomposing body, allowing everyone to see its bones, to see a house’s intimate spaces, for the holes and cracks were now gaping. To look into the interior of a house was to see all we possessed, secrets that should never be revealed, secrets fundamental to who we were.

Would you mind talking a bit about your Farm Management Instructions pieces and how buildings, houses, and their decay factor into this work, which reckons with Brazil’s history of slavery?

What is described in Itamar Vieira Júnior's book is the exact point where Brazil’s history and memory collapse. Many of these plantations, where people were enslaved, tortured, and killed, are now “paradise” tourist destinations that even host bizarre theatrical representations of the relationship between plantation owners and their enslaved people. It is where a lack of awareness is cruelly evident, a result of historical erasure stemming from a school education grounded in the white European perspective.

The series Farm Management Instructions (or “Instructions for the Administration of Plantations”) is my most extensive series and began with a letter of that title displayed in the Afro-Brazilian Museum, whose content is an inventory of social relations in Brazil.

Farm Management Instructions 2, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, (177x223 cm).

In several of your paintings, particularly from that series, sometimes in a tile pattern, there’s a motif of workers holding a tree above a large hole or void, as if they might plant it there, or else drop it in. I wonder whether you could talk a bit about this image, its provenance or resonance for you?When I began my artistic practice in 2009, I photographed two trees from different places. One had been completely pruned, and the other was being uprooted and had only a piece of its trunk left. When I created a montage of these two photos, I had no idea I would become a painter, but this reference has followed me and appeared only in my paintings. For me, it is a symbol of a plantation landscape, of extraction, representing what Brazil was like as a colony. It never appears alone; the enslaved people are there to highlight the conditions under which Brazilian society emerged and how this is still present today.

Tree. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Your exhibitions (including your current one), though painting-focused, often include installations or elements of installation. Why are some works represented in a more sculptural or three-dimensional format (even including sound, in one case), while others are realized on canvas?It’s a particularity of the medium; often, painting is not able to fully convey an idea, even when it is also used to compose these installation works. Such is the case with the installation The Materialization of the Song of the Mother of the Moon, which I recently exhibited at the Eva Klabin Museum.

The title of the work uses the popular name of the potoo, a nocturnal bird typical of South America. The bird has a characteristic melancholic song that is associated with various folk tales, most commonly understood as a bad omen. The installation comprises the sound of the potoo’s song, two portraits, and a selection of objects. Each element fits into the category of masculinity or femininity, pointing to the intrinsic violence of the former versus the oppression of the latter, representing the traditional patriarchal structure and its implications for society and national politics.

I’m curious about your training and experience as an architect, and how you bring that into your painting. Your interiors, which sometimes show wiring exposed through the wall, or intricate tile patterns, reveal the eye of someone with an awareness of what underlies the spaces and the ways spaces act upon their inhabitants. How does that training come into play in your painting process and in your installation work?

Architecture was a stepping stone for me to become an artist. My first artistic experience occurred while I was studying the retrofit of vacant buildings in Rio de Janeiro. The emptiness of those ruined spaces made me think beyond the architect’s role of designing, constructing, and occupying. This led me to almost nullify architecture at the beginning of my artistic journey. It’s curious to make this analysis and realize that architecture reappeared in my works as I delved deeper into the practice of painting.

I’m intrigued by your series called Empty Annunciation, which “translates” several annunciation paintings by Fra Angelico (and others?) into pieces in which the figures have been set at a remove from the settings or buildings in which they were originally portrayed, and the architectural elements are shown as empty. To me, these paintings seem to arise from the tension between the peopled and unpeopled works in your œuvre. Could you say a bit about how these came to be and about your own engagement with portraiture. I’m very moved, in particular, by a very different series, the haunting Distant Eyes Camouflage Themselves in the Scenery.

It’s interesting how this question aligns with my previous response, because the emptiness and silence of the mentioned ruins are what I seek in my paintings. The series Empty Annunciation refines this idea of emptiness, where the characters are organized like a legend, a memory of what we understand about that narrative, using architecture as a vehicle.

Empty Annunciation 1, 2019, oil on canvas mounted on wood and oil on plywood, (73.7x38.5 cm).

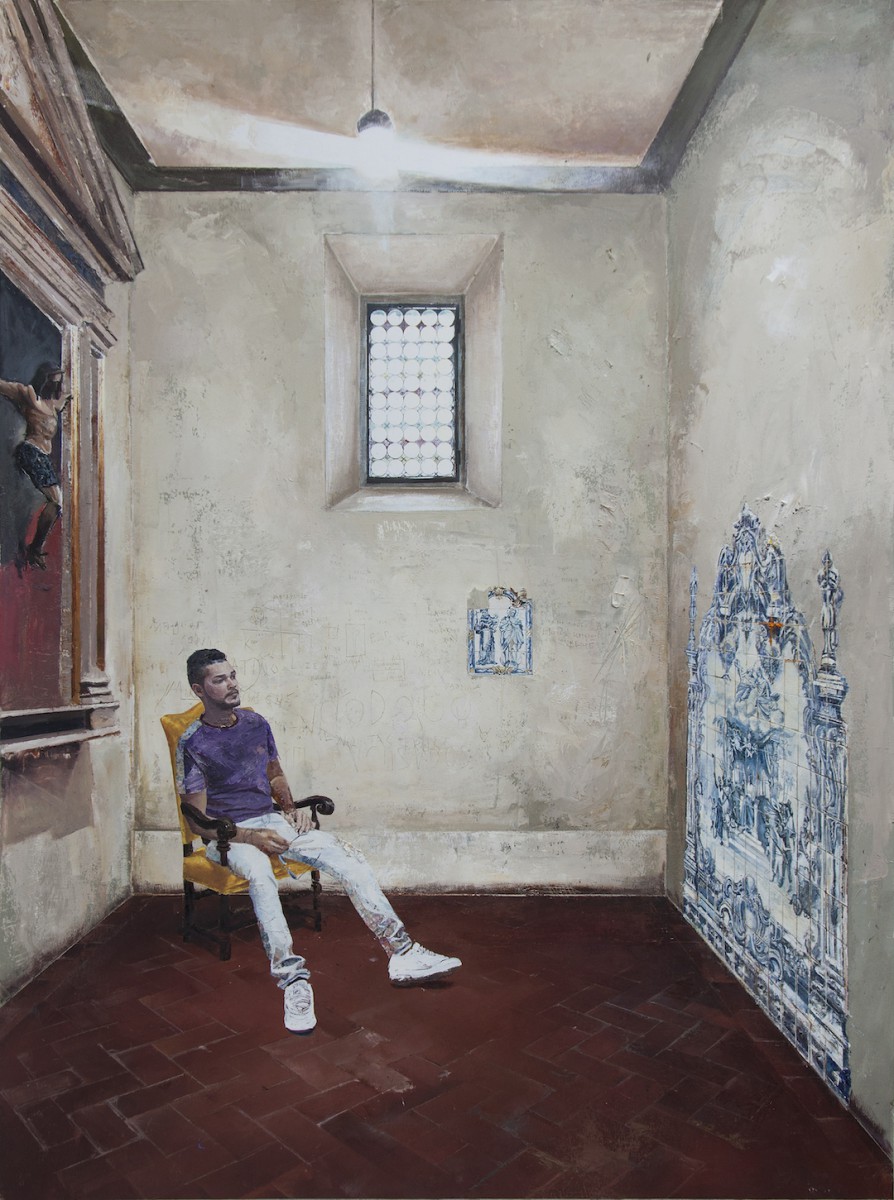

In contrast to what I had done up to that point, in Distant Eyes Camouflage Themselves in the Scenery, there is a human figure as the main reference. Indeed, this marked the beginning of my interest in portraiture, where the body is the subject. The man, mixed-race, sits in front of a tile panel depicting a nineteenth-century drawing by Jean-Baptiste Debret, commissioned to commemorate the establishment of the republic in Brazil. The main concept was to praise the creation of a mixed-race and egalitarian country. The idea was to confront this romantic republican historical document with this central figure, an allegorical representation of this mixed-race country, two hundred years later.

Distant Eyes Camouflage Themselves in the Scenery, 2021, oil and acrylic on canvas, (177x133 cm).

I’ve noticed several interconnected strains of political and social critique in your work, one of which is a critique of religion as a mode of social control. In works that respond to paintings by Giotto and Fra Angelico and to Brazilian churches and altars, to name a few examples, you use religious iconography itself to ironize or make visible the ways that iconography acts on its viewers. However, your painting is so rich, detailed, and at times almost immaculate, it seems to go right to the edge of glorifying the imagery, and then it turns, sometimes into something quite violent. Could you talk a bit about your relationship to the artists you reference, and to the idea of beauty in your work?My relationship with the artists I research is one of deep admiration, even when the themes they address are subjects of critique. There is a current example of this Artist vs. Subject issue worth mentioning. I am dedicating a series to the Basilica di San Francesco in Arezzo, where the altar was painted by Piero della Francesca. Being there was one of my greatest artistic experiences, but it is strange to imagine that this work is based on a narrative that even the church no longer defends—that Constantine’s conversion to Christianity happened after dreaming of a cross with the words “In this sign, you will conquer,” the night before a crucial battle. The historical fact is that General Constantine legalized Christian worship as a political maneuver, needing popular support to become emperor of Rome.

This paradox between the narrative created by the church and the historical fact interests me greatly and is the type of conjunction that generates many works. I can say that this is when a certain cynicism begins on my part, using the same aesthetic artifices that underpinned the ideas of beauty, the sublime, and the divine to expose and confront values constructed by the church.

The critique of religion extends beyond a critique of Catholic imagery into the consolidation of power of new evangelical forces in Brazil with politics and local militias, which include police and control access to water, gas, and other basic goods on the outskirts of your home city of Rio de Janeiro. Can you talk a bit about the development of your series of work depicting “the seller of figurines”? How did you come to make these figurines, and portray their sellers, and what forms have these figures taken so far?

In 2019, my work was heavily focused on historical themes. However, Brazil was going through a problematic period that began with the parliamentary media coup that ousted President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, followed by the rise and election of President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. A lot was happening, and I needed to address those issues in my works.

To Whom Should I Pay My Indulgence?, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, (177x223 cm).

The series The Seller of Miniature Characters was preceded by two works, To Whom Should I Pay My Indulgence and There Is Dirt Underneath the Dirt, which critique Bolsonaro’s policies, his closeness with charismatic evangelical churches, and the support from the military for this figure. Not coincidentally, this political-religious-military combination forms the basis of the militias in Rio de Janeiro, a type of parallel organization that controls low-income areas through armed imposition.

There Is Dirt Underneath the Dirt, 2019, oil, oil pastel, color pencil and graphite on canvas, (177x223 cm).

The series The Seller of Miniature Characters emerges in this context. It features a fictional character who occupies train and metro stations to sell his figurines, representing the different power systems that operate in the city of Rio de Janeiro: pastors, police officers, politicians, drug traffickers, and militiamen.

The Seller of Miniature Characters, 2020, oil pastel, color pencil and graphite on canvas, (177x223 cm).

There are two key ways I notice text coming to life in this work: one is in the evocative titles, like voarei com as asas que os urubus me deram, (the title of one of your shows, which can translate to “I fly with the wings the vultures gave me,” and makes its way into The Progress of Retrogression as graffiti on a window) and in the writing that appears in the paintings, as signage in a subway station, Latin around the border of a religious painting, or an ominous messages taped to a wall, as in Distant Eyes Camouflage Themselves in the Scenery 2, where the note says (as I’d translate it) “use your weapon on yourself, you s.o.b.” First, I’m curious about whether your titles predate your paintings or usually come later. And secondly, do you often invent the graffiti or street signs, or are they usually there, serendipitous? I’m thinking of a subway sign near a figurine vendor that says “no exit” or “wrong way,” for example.I prefer to start a painting with the title already defined, but there have been times when I named a work months after it was finished. In addition to titles, writing appears in other forms, ranging from tiny almost imperceptible texts to graffiti, posters, papers on the ground, signs, televisions, and so on. I have a series called The Progress of Retrogression in which I reproduce newspapers in a way that makes it possible to read the entire content of an article.

The phrase you mentioned, “use sua arma em si, seu FDP,” is a critique of Bolsonaro’s policy to liberalize civilian gun ownership in Brazil. During the 2018 election campaign, an armed rhetoric emerged among his followers, who symbolized their support by making a gun gesture with their hands. I used Bruce Nauman's 1985 work Sex and Death by Murder and Suicide as a reference to subvert the use of this symbolism.

Congratulations on your recent monograph! This marvelous art book features the poetry of Brazilian poet and translator André Capilé (in both Portuguese and English), written in response to your work. Because Asymptote is primarily a literary journal, I wonder whether you could say a little about how this collaboration came to be?

Thank you, it has been a great pleasure to present this book to you. My intention, in including André Capilé's poetry in the book, was to enhance the artistic character of the publication, differentiating it from the rigid format of a catalog.

I met Capilé when we were teenagers in Barra Mansa, a town in the interior of the state of Rio de Janeiro. We took different paths but reconnected through our mutual admiration for each other’s work. The importance of his poetry was such that some paintings in progress at that time were influenced by his poems. For example, the last painting presented in the book, Where Drunk Angels Are Arrested for Flying with Their Demons, was in process, and I titled it with a part of one of his poems.

Where Drunk Angels Are Arrested for Flying with Their Demons, 2023, oil and acrylic on canvas, (177x252cm).

*

Excerpt from André Griffo by André Capilé (translated by Georgia Fleury Reynolds)

to summon, each object conjured,

what is coming—impermanent,

in what happens in your studio

—what the audience silences: the shaft

of illuminated night that dissects

the dry trunk—the inviable structure.

there are saints who pose the question

— no rocket will show its feet.

the bird in the hand, the cage ajar

in or out, what else protects us?

the hand that cradles, saws the branch. Bewilders.

through its cloistered spaces

the calculation of remembrance

through the kidneys of history

diffusion tiles the soot

at the walled station

investigate dead-end corners

where motives are stationed

without rest — pupils refine the wreckage

*

renounce renouncement, in their announcement

of eternity in alleys and sidewalks

drenched in blood, where drunk angels

are arrested for flying with their demons.