Photo credit: Emily Poe-Crawford.

Award-winning artist, editor, writer, and activist Katie Holten’s anthology The Language of Trees, published by Tin House in its American edition with the subtitle A Rewilding of Language and Landscape, collects essential essays, manifestos, aphorisms, fiction, poems, and other writings that celebrate our ever-branching comprehension of trees and our relation to them. Each piece appears in two radically different forms: The first legibly in English, the second a forested translation in an invented typeface called Trees. The result is, in Holten’s words, “a book about trees written in trees.”Holten first devised the Tree Alphabet for an earlier iteration of the anthology produced as a 2015 limited-edition artist’s book, titled About Trees, the inaugural volume in Broken Dimanche Press’s series Parapoetics: A Literature Beyond the Human. In a 2015 interview for the Asymptote Blog titled “Translating Borges into Trees,” Katrine Øgaard Jensen and Holten discuss that publication, the graphic roots of Holten's Trees font, and the value of indecipherable language.

During the summer and fall of 2023, Holten and I picked up the conversation where she and Jensen left off. We discussed the editorial vision of this new anthology, with its many new contributions, now available as a commercial volume in English-language bookstores around the world, the concept of “rewilding” itself in her arts practice and activism, the relation between those practices, and how this anthology relates to other drawing series in her work.

In 2015, Broken Dimanche Press published the first version of this anthology as a limited edition artist’s book. The new, much larger anthology, The Language of Trees: A Rewilding of Language and Landscape, which was released in clothbound hardback by Tin House in 2023, has become a national bestseller, and comes out as a trade paperback this month (April 2024). What has changed for you as an artist, writer, thinker, reader, and editor over those intervening eight years? Are those changes expressed in the new book, and how is the new book itself different?

So much has changed! About Trees was published in September 2015 on my fortieth birthday. I wanted the book to celebrate, through trees, a short lifetime of thinking and being on this beautiful planet. Then everything turned upside down! Brexit and the 2016 US election were traumatic events. Much of what I had taken for granted was suddenly shattered. I was horrified. I spent most days protesting in the streets, fighting to protect rights that were being stripped away from so many. Greta Thunberg started her climate strikes in August 2018. Extinction Rebellion formed in October 2018. In 2019 I cofounded Friends of Ardee Bog and we took the Irish government to court to stop them from building a road through the peatland. Then the SARS-CoV-2 virus jumped from a nonhuman being into a human being. We’re still living through that history, which has changed all of us. I have long COVID, so my body has changed in ways that I’m still trying to understand.

For me, About Trees was a way to create an archive of knowledge filtered through branches of thought, tracing a shift in consciousness from capitalist anthropocentric thinking to an understanding that our way of life has created a new geological epoch that some call the Anthropocene, or Capitalocene, or Plasticene. I hoped the book might act like a time capsule—a gathering together of things that show what it is to be a human on this beautiful planet Earth at this moment. So, when Masie Cochran, editor at Tin House, invited me to publish a “beautiful book about trees” eight years later—About Trees in a new form—it was important to me that I include new material because the world had changed so much in those years, as has my thinking.

Those of us who are facing up to the Climate Emergency are trying to learn how to live with the knowledge of what our species has done. We are frightened for the future of life on Earth. How can we stop things from getting worse? Most importantly, how can we let everyone know—there is still time to make a difference?

What is it to be a human being? What is it to be part of a community? How can we communicate with each other? What is the language we need to live right now? How can we learn to be better lovers of this Earth, and of each other?

We’ve been so busy rushing towards “the future,” searching for quick fixes, that we’ve forgotten who we actually are.

I have spent decades making artworks that felt important and urgent at the time, but they never seemed to create any real change in the world. I want to help. The sense of urgency is overwhelming.

It became more and more important to share my work directly with people. Books are not perfect, but they are egalitarian spaces, more so than art spaces. (What’s happening in the US now with book bans and library closures is really disturbing and shatters this notion, but I’m clinging onto it!)

The main difference between the original book, About Trees, and The Language of Trees, is the size of the print run and the means of distribution. I’ve always made zines and books and was happy that they found a home within art world distribution sites. About Trees changed that. I could see there was a hunger for the book. May Castleberry, editor of MoMA’s Library Council publications, describes me as being “on a mission.” I guess I am on a mission! I feel it’s important this book and these stories get out into the world and as many people as possible hear the message, so then you need distribution. About Trees was a limited-edition artist book available directly from the indie publisher, Broken Dimanche Press, whereas Tin House can produce large editions and distribute to indie bookstores across the country. The scale is completely different!

Another obvious difference is the physical aspect of the books. About Trees was printed on beautiful Munken paper, harvested sustainably from trees within their own forest in Munkedal in Sweden. Practical and financial reasons make it impossible to use something this sumptuous for our large US edition, so we had to find another paper. Richard Powers helped us! When Richard was working on his novel The Overstory he asked Norton, his publisher, to find a good paper that doesn’t harm trees. Beth Steidle was the production manager on The Overstory. She found a nice, recycled paper. Incredibly, Tin House hired Beth to work on The Language of Trees, and we were able to use the same paper. When I met Richard years ago at his New York launch for The Overstory, he told me he was inspired by my Tree Alphabet. So I was thrilled that he graciously shared his words with me for The Language of Trees, and I love that he’s part of The Language of Trees at a cellular level, in the paper.

In the new iteration of the book, it was very important to me that I include more voices, including work from different cultures as well as indigenous writers, poets, and activists. Masie, my editor, was happy to let me use the precious production time available to find and confirm rights for new contributions. I am honored that Winona LaDuke’s words open the first chapter. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work has been so influential, so it felt vital to include her essays on the grammar of animacy and “Speaking of Nature.” There is also new material from Ada Limón, Amitav Ghosh, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Nemo Guiquita, Sumana Roy, Maya Lin, Carl Phillips, Suzanne Simard, and others. What joy that Ross Gay offered to write the introduction! The book feels like a community, an extended family sharing stories.

We are living through a traumatic and terrifying time. We need a change in worldview, away from human exceptionalism, to embrace our place as creatures embedded in the web of life. We are one species among millions. We could not survive without the other beings we share this planet with. I made the book as a love letter. We exist thanks to trees and plants and their leaves photosynthesizing. We are family. Where is our ecological compassion? I feel this so strongly and I believe others do too. Let’s embrace it. Together we have the potential to create the most beautiful community in harmony with this precious planet.

Yes, and that kind of harmony, it seems, will require many changes. This brings to mind the first term of the new volume’s subtitle, “rewilding.” Might “rewilding” serve as a key into how your thinking about this project has progressed?

Yes! When my editor asked me for a subtitle, I wanted it to include “Rights of Nature.” The book is part of my campaign to support the global Rights of Nature movement. But I couldn’t find a way to get the term to slip off the tongue! Rewilding is a more accessible concept. I love that rewilding can refer to anything. Rewild your garden. Rewild your imagination. Rewild your heart. Rewild your life.

Including the word “rewilding” in the subtitle felt like a nice way to introduce people to the concept, which still seems to be pretty new here in the US, while also sharing on the cover what the book celebrates and hopes to inspire—a rewilding of hearts, minds, and land.

About Trees was published in 2015. Since then, it feels like there has been a shift in our understanding and appreciation of the urgency of the Climate Emergency. People are searching for ways to do something. Ireland declared a Climate and Biodiversity Emergency in May 2019. Rewilding has become a common term that everyone there has heard of by now. There is a movement to create space for biodiversity by rewilding our urban and rural landscapes.

An incredible thing has happened. In just the last few years, we have discovered—remembered—that Ireland is a rainforest ecosystem. Through recent rewilding efforts by people like Eoghan Daltun, Ray Ó Foghlú and others, we are finding remnants of the lost and forgotten Irish Atlantic Rainforest. How on earth can we have forgotten that this was our history? It’s mind-blowing!

So much of this work is about simply slowing down to see what’s become invisible to us. Capitalism speeds everything up to a frenetic pace that we literally can’t keep up with.

Rewilding—and the Tree Alphabet and The Language of Trees—are invitations to slow down. We all need to slow down. In her contribution to the book, Mary Reynolds offers ways to slow down and create our own local rewilding projects. Mary calls them ARKs, or Acts of Restorative Kindness. An ARK is a restored, native ecosystem, and we are all invited to create our own.

Does “rewilding” in your mind relate in any way to how you see artmaking in general, in all or any of the art disciplines in which you work? Or is art more a taming? An unwilding?

I love this! I hadn’t thought of it this way. Yes! I could see what I do as a rewilding.

Your question invites me to reread the definition of rewilding and think of it in terms of my own work. Rewilding is a form of ecological restoration aimed at increasing biodiversity and restoring natural processes. It differs from ecological restoration in that, while human intervention may be involved, rewilding aspires to reduce human influence on ecosystems. A key feature of rewilding is its focus on replacing human interventions with natural processes. The aim is to create resilient, self-regulating, and self-sustaining ecosystems.

Making art, for me, has always been a way to look at and learn about the world. It’s how I’ve come to understand my place in the world. Some of my earliest works played with self-regulating systems. I studied complexity at the Santa Fe Institute. I’ve always hoped that my work—whatever form it takes—invites viewers into dialogue with the natural processes taking place in the specific sites where my work is placed.

Though I’ve always enjoyed working between disciplines—art can be a useful way to break down barriers between different fields of study—most of my work is drawing-based. Drawing is a tool of knowledge, a way to draw out how we’re all connected and in relationship with each other—human and the more-than-human—and the world around us.

It starts with simple questions. The process of finding answers leads the way, via research, walking, and conversation. Then the process itself creates the work. I just listen and follow.

I’ve also always worked with what’s at hand. I’ve never had money and don’t have my own home or studio, so I’ve always had to make do with what’s around—no fancy art supplies and no art storage. So, recycling has always been a very natural way for me to work. Now that I know about the term rewilding, I can see that this is how I’ve tried to work as an artist—letting life (the work) find a way. My input on things should always be minimal.

Your question makes me wonder if this is at the heart of my disconnect from the “art world.” The art market insists on what we could call a taming, an unwilding, as everything has to become a product that can fit within the system in order to be bought and sold. I have never felt comfortable in that system. I used to naively think the art world would find ways to crack the system that’s breaking the planet, but even COVID wasn’t able to slow down the art fairs and art cycle—it’s only speeding up, faster and faster. The horror! But we need art. It’s part of what makes us human. So I continue to wrestle with this conflict.

This question touches on why it was so important for me to include other visual artists in the book. Andrea Bowers, Amy Franceschini, Luchita Hurtado, Natalie Jeremijenko, Charles Gaines, Fritz Haeg, Maya Lin, Pedro Reyes, and Andrea Zittel have all created bodies of work that explore the possibilities for rewilding the art world.

As an artist, in addition to drawing, you have often returned to the form of the book. One immediately notices the editorial art of this book, the abutment and placement of things. How did you go about compiling these texts, songs, and quotations, and ordering them?

I love books! I have always loved books. Books are magic, like gems, time capsules, memory banks, containers of knowledge, repositories of everything that ever was, or ever could be.

The word book itself is beautiful. Two round o’s, like pools you can dive into.

As Ross Gay writes in his introduction, the word beech is the proto-Germanic antecedent for the English word book. The words for book in some other languages too derive from or overlap with words for trees. Books—always and forever related to trees!

When I was little, I loved reading encyclopedias, dictionaries, atlases. We lived in the middle of Ireland, in the middle of nowhere, but I could travel anywhere with my finger, following marks on a page.

About Trees, which is at the heart of The Language of Trees, was compiled alphabetically by author. It was made so quickly—in an act of urgency, it was published in six months—that there wasn’t time to move things around. I compiled everything alphabetically to keep track of it all. I worked directly with the designers to translate it all into trees, working from A–Z.

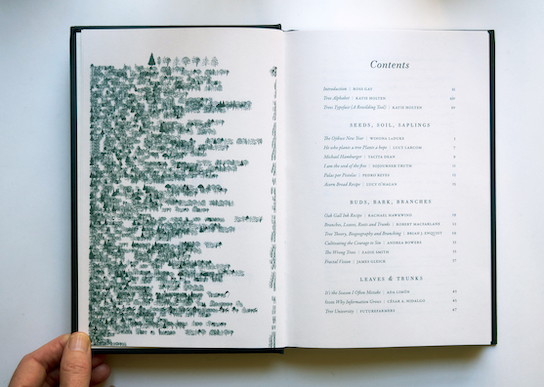

My editor at Tin House was excited to see how the content could be rearranged in The Language of Trees. I knew that the trees would show me what to do, so I let the trees guide me. The contents of the book slipped into different sections or chapters based on different parts of a tree, from seeds, saplings, buds, and flowers to leaves, trunk, branches, forests, roots, etc. The trees themselves showed how the book should bloom and take form.

The Language of Trees, table of contents

Making the book was a way for me to share the importance of caring and creating connections between different times and places, peoples, plants, and histories. The book form is such a wonderful way to share myriad points of view. First person plural is an organic way of storytelling. We are community. Our histories are not linear and not as simple as we’ve been told. I’ve always loved compendiums. It feels like an organic way to share our collective story—weaving texts together, creating a narrative thread that unravels and is left up to the reader to weave back together into their own pattern. The book can be picked up and read in an infinite number of ways. Everything is contingent. You can get lost. That’s okay.I love how the different parts of the tree become an organizing principle for you as an editor. That approach to the editorial art of this volume is coupled with your own drawings, and typographical art or design, in which the texts are turned into forests of various shapes on the page, forest-paragraphs composed of your tree font. Some are wilded, presented as prose, filling the page from margin to margin, filling the landscape of the page, the field of the page, if you will, but others are tended, cultivated, as with the two circular presentations of the text in your tree font for Tacita Dean’s essay as two circular forests. How did you come up with the various “forest” manifestations for these texts, as they are so different from one another?

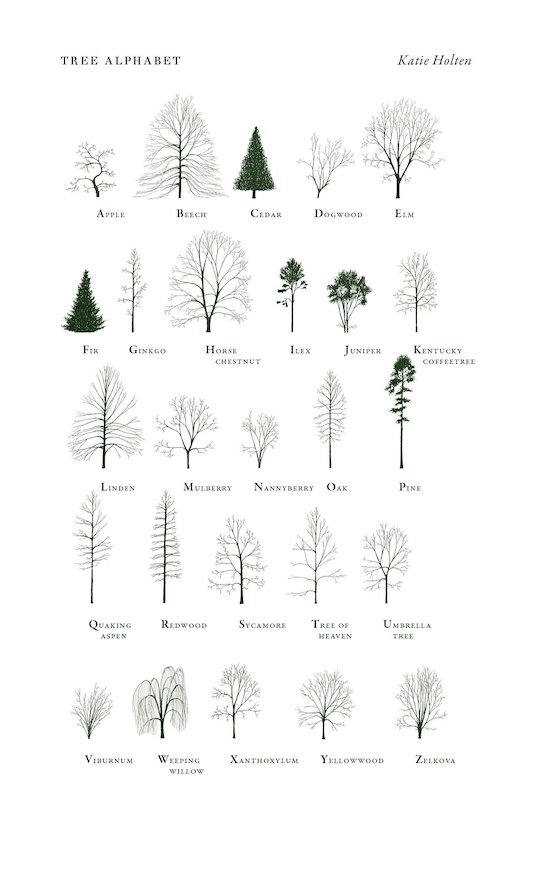

It’s very simple! I used my Tree Alphabet to make a font called Trees. By simply changing the font I can “translate” anything into Trees.

Letter by letter, tree by tree, each text blooms into its own forest. The texts themselves let us know how they should be translated. For example, if they’re short, then there’s enough space on a single page of the book to share each letter and tree side by side, so the reader can translate and “read” the trees.

I love that the longer texts make that act of translation impossible. Longer essays become impenetrable, like a dense forest. We can’t always read what’s on the page or see the trees for the forest.

This natural contrast between very short texts—a single word or a sentence—and longer essays with thousands of words creates a nice rhythm to the book with spaces between creating breathing room where the reader can pause. Breathing space is important!

This book has no beginning, middle, or end. You can pick it up anywhere and wander the pages, like walking through trees. And although Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder’s essay on migration is a beautiful ending, with trees migrating across the pages, the book does not conclude. I wrote an epilogue, “After Trees,” that invites everyone to download the Trees font and write your own forest. I include a (very long) bibliography that invites readers to continue their arboreal journey.

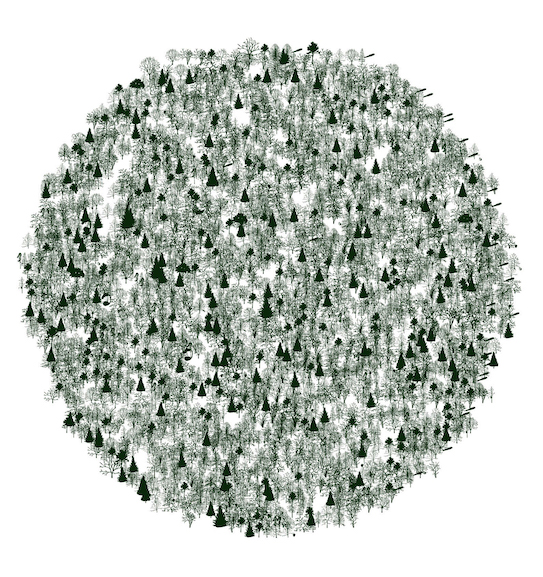

Originally, all of the forests were rectangular “fields” filling the book page. I found it repetitive, so I played around with the formatting. Amy Harmon’s essay is about oranges, so I asked the designer if she could turn that forest into a circle. Circles, like trees, are iconic. A circle can represent the Sun, Earth, tree rings, the cosmos, or circular tree time.

Amy Harmon, “Millenniums of Intervention” (translated into Trees), The Language of Trees, p. 80

Tacita Dean’s art practice uses the motif of the circle a lot—the circle of an eye, a camera lens, the sun. So it seemed right that her essay would be repeating circles.Fractals are important. I included James Gleick’s little story about Benoit Mandelbrot as a nod to the history of our understanding of the concept. So I was curious to see what Jim’s forest would look like as a fractal. The UK designer created a beautiful fractal forest and the forthcoming US paperback edition will include a fractal forest.

It was always important to me that these books be beautiful objects. The subject matter couldn’t be more simple (or more serious)—trees and human nature and the future of life on Earth. The exciting challenge was to create a book that is both beautiful and deadly serious, while also being humorous, playful, thoughtful, and profound—all at the same time.

The Language of Trees is about trees, of course. Trees are our guide. But the book is fundamentally about us, humans. The Tree Alphabet is a (wo)man-made language. What can trees teach us, what have we learnt from trees, what can we do with this knowledge to make the world better?

Many of the texts that I’ve compiled look at ways we’re embedded in—and have affected—the landscapes around us. Elizabeth Kolbert writes about “Islands on Dry Land” and how our species has hacked into, and through, every wild place on the planet. Creating unnatural lines in the landscape—slashing through rainforests, installing pipelines—we are literally changing the shape of the world. The forest translation of Kolbert’s essay has a white space/slash through part of the text. This is just the paragraph break! It’s uncanny how it visualizes the slashing through the actual rainforests that she describes in her essay. I love that!

Things in the world have a way to communicate that performs beyond our human notion of language. There’s a reason why things are the way they are. There’s a reason why trees are structured the way they are. Brian Enquist talks about that in his essay “Tree Theory, Biogeography and Branching.” You could say that this natural language is a code that’s been developed over millions of years. We are only a recent animal, a baby, not very old at all in planetary terms. Humans are not developed enough, or sensitive enough, to “get” these other forms of communication. To us it’s all just indecipherable, messy, “nature.” We have so much to learn. If only we could be quiet and humble enough to listen.

You’ve spoken about how trees connect to language. Could you describe the relation in your mind between trees—as beings in the world, as beings that have, in part, with other plant life, formed our world, made its soil, made its oxygen-rich atmosphere—and art, both visual and literary?

I think trees have always held a special place in our consciousness. Humans revere trees. Most cultures have sacred trees. Trees appear in ancient texts. In Ireland, we had the Brehon Laws: the first laws of the land, dating back to the seventh or eighth century. The worst thing you could do was kill a tree and there were steep penalties for those who did. So, the Rights of Nature existed back then! (Another example of how much we’ve forgotten about our relationship with land and home.)

I believe there has always been a deep kinship between humans and trees. It’s as though we were forced to forget that (along with our native languages and culture). In Ireland, our medieval Ogham script was no doubt carved onto trees. The very form of how the characters were written—a branching stem growing from the ground up—mimics how plants grow. Our language back then, it seems to me, was inspired by and in communion with plants and the basic tree form. In his contribution to the book, Aengus Woods writes beautifully about Ogham and our evolving relationship with communicating via mark-making.

How we speak of ourselves as individuals, as families, and as communities is reflected in how we see trees. We are rooted, grounded, branching—our roots go deep. One section of the book is called FAMILY TREES. It opens with “Being,” a poem by Tanaya Winder, which reads:

Never forget you were put on this Earth for a reason—

honor your ancestors.

Be a good relative.

Our family trees reach backward and forward through time. Why is it taking us so long to embrace tree time? It seems to me that our old notion of time is outdated, just as we eventually came to realize that ”flat-earth thinking” is wrong. I grew up believing that time is linear, running from the past (behind us) to the present (today) on into the future (in front of us). A straight line. But isn’t time circular, cyclical, like tree rings? Winona LaDuke writes that the Ojibwe know the New Year has arrived when the sap rises in the Maple trees: “Land determines time . . . In the Anishinaabe world, and the calendar of our people, there’s nothing about Roman emperors like Julius or Augustus . . . In an Indigenous calendar time belongs to Mother Earth, not to humans.”

As Luchita Hurtado told Andrea Bowers, “Trees breathe out. We breathe in.”

Breathing is life. Living is breathing. Plants with their leaves created our atmosphere. We are plant people. We wouldn’t be here without the trees.

Ironically, I made The Language of Trees while experiencing breathing difficulties. As the book went to print, I was diagnosed with dysautonomia. Dysautonomia is a form of long COVID that affects your autonomic nervous system: heart rate, blood flow, etc. My body forgot how to breathe!

Living with dysautonomia has deepened my sense of being a living creature on the planet, in this atmosphere. Now my body acts in strange ways. When I stand up, all the blood flows down. I’m breathless and dizzy. My heart works overtime. Even sitting upright in a chair can be work. My body thinks it’s running a marathon. I have to take a lot of water and electrolytes. I don’t have enough oxygen. Everything slows down. At times, it feels like I’m walking on another planet, in another atmosphere. All of this makes me very aware of being a living, breathing creature on a rock hurtling through outer space. But when I walk, very slowly, down the street I get a sense that many people rushing past are not aware that they are on a planet. I mean, the sense of disconnection feels so deep as to be unfathomable. It feels to me as though our species is suffering from a form of dysautonomia.

How do you see some of your drawing series, like “Cities,” “Love Letters,” and “Stone Alphabet,” for example, as similar or different from the tree projects? Your drawings of cities and of migration patterns both show the shapes of patterns that might not otherwise be visible, and the way they include human activity as something to be traced in the same way you might trace other activity we would call “wild” or “natural.” Both of those projects might lead one to think of Adrienne Marie Brown’s Emergent Strategy (AK Press, 2017), and also about time—a sensitivity to timescales different to the ones we humans usually perceive—like the “tree time” you mention in the book, as crucial to “seeing.”

Kaite Holten, City Drawings, “Dublin, remembered,” 2007, ink on paper, 30 x 22 inches.

I love that my drawings bring to mind Adrienne Marie Brown’s Emergent Strategy. Drawing is the simplest way for me to communicate. I like drawing things out, drawing connections. It feels like the right thing to do, organic and true.I tend to work iteratively. This is a way to let nature do its thing. The process takes over and results emerge.

I suppose it’s also a meditative exercise. Sit with something quietly. Let the act of studying something lead you. You don’t know where you’re going to end up. Make a mark, see where it leads.

Drawing out the invisible feels important to me. In the same way that you can’t tackle a difficult question without first breaking it down into the components, once you look at something closely you see how it contains the whole universe.

I am slightly obsessed with trying to visualize invisible things and the hidden connections between things. I see what we humans do as being just another part of the interconnected system of this planet. Our movements, at every scale, are related to those of every other living being and community of beings. When we look inside our own bodies, at a cellular level, we see what looks like galaxies in outer space. The universe is inside us! We are all made of stardust. Indeed, it is now well documented that we’re each made up of more bacteria than human cells. We contain multitudes. This complicates our whole notion of what the individual is. What is the “I” at the center of our universe? (In the Irish Tree Alphabet, the letter i is Iúr, a Yew tree, sounds like “you”. I is you!)

Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Jennifer Croft, believes that “the sin for which we were exiled from paradise was not sex, nor disobedience, nor even finding out God’s secrets, but rather considering ourselves to be separate from the rest of the world, to be individual and monolithic. We simply refused to be in relationships.” I read this and realize that’s what my work is about—trying to engage and be in relationship with the world. I love looking at these self-similar patterns all around us and drawing them out. Who doesn’t love fractals? Studying complex systems was an opportunity to learn the extraordinary way that life repeats and mirrors itself at different scales like an invitation for us to fall in love with the world. Everything contains everything else.

Over the years I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about growth: plants growing, cities growing, etc. So it’s fascinating to explore the concept of degrowth. (Trees know when to stop growing. Humans don’t—we keep digging and building and devouring the planet. How can we learn from trees?)

My City Drawings were simple exercises: could I draw maps of places I’d lived in? I had a geography teacher who drew the map of the world on the blackboard. He drew it freestyle, from memory. It was pretty cool, and years later I tried to do it myself. Cities are alive, they grow. When I draw out a city I am remembering streets where I’ve lived, where special things happened, routes I’ve walked. The memories draw out streets, which grow from other streets.

Have you ever tried to draw the map of the world? We all know it! The map of the world is reproduced everywhere. But what happens when you sit down to draw it?

It's similar to what happens during “blind drawing” exercises. Get a piece of paper and a pencil or pen. Look at something and draw what you see, without looking at the paper. Fun! It doesn’t matter what the end result is, or what the marks on the paper end up looking like: the exercise—the fun—is in the deep looking. You can get really lost in noticing, in looking closely. You might even feel your brain and eyes and hand talking to each other. Magic!

The act of drawing is powerful. A simple “blind drawing” exercise helps you see the difference between what your mind sees and what your eyes and brain see. You don’t need fancy art supplies or special tools to investigate the world.

The Stone Alphabet was a way to dive deeper into the alphabet itself. The Tree Alphabets that I’ve made all respect the concept of the alphabet, replacing each letter A–Z with a tree. My Stone Alphabet proposes an infinite alphabet—each character is different. There is no constant monolithic A or B or C. Each time you use “A,” the symbol representing A looks different. In that sense the alphabet is alive, changing. I drew the glyphs directly from life, from the stones. For Emergence Magazine, I created a Field Guide to Reading and Writing the Stones of New York City. That was a fun exercise in looking at the infrastructure of the city through the stones that make it up, at all different scales from bathroom sinks to sidewalks, buildings, walls inside museums, fossils embedded in the façade of Rockefeller Center, and the bedrock poking out in Central Park, etc. The stones have a story to tell, an alternative history, if we can only slow down to notice.

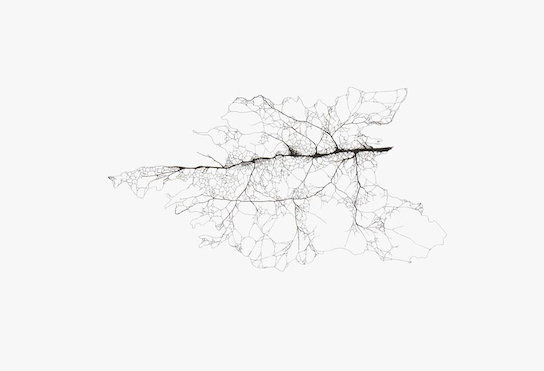

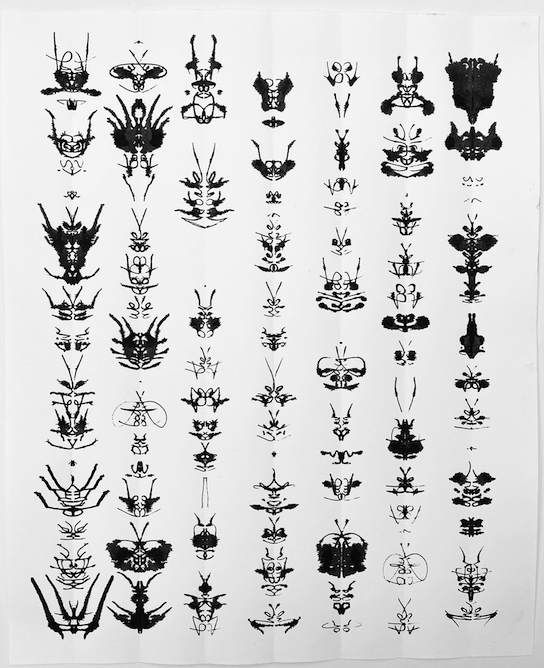

The works in the series Love Letters were made during lockdown. It was a way for me to acknowledge the power and beauty of words. These drawings are all made using English. I simply write each letter, in ink, and then caress it like a pressed flower. Each letter forms a mirror of itself. Playing with ink like this, it obviously brings to mind Rorschach images, but it’s also a way to play with the physicality of language. Language is not merely ink or a font or symbols. The poet Natalie Diaz has said that text is a physical space for her. I agree, language is not just abstract or, indeed, formal symbols typed on a screen—it’s something that lives and breathes. Language is alive—words evolve. Linguists today are excited to be able to follow the evolution of words in real time. So, planting words with trees makes a lot of sense to me!

Katie Holten, Love Letters 2021, “‘The First Water is the Body’ Natalie Diaz,” 2021, Ink on paper, 18 x 24 inches.

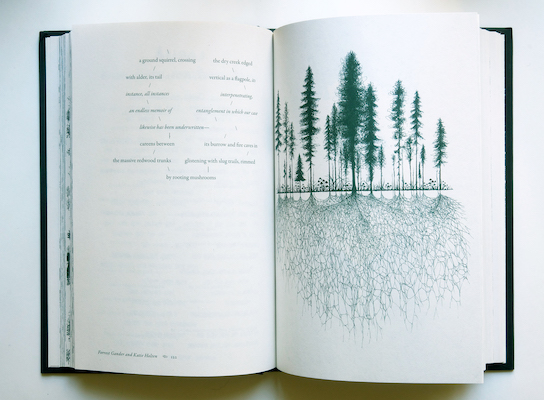

In your afterword to the new volume, you also describe your process in terms of translation, a process that is always relational, a kind of collaboration you describe as “the most intimate form of reading.” You’ve spoken publicly with poet Forrest Gander about this.Yes, I think all of my work grows out of conversations with others. The forest drawing on the cover of the book was created in collaboration with Forrest. Emergence Magazine invited the two of us to work together to create a multimedia piece for their second print volume. In the autumn of 2019, I visited Forrest in Northern California and we spent a few days walking in the Redwood forests. It was pretty fabulous. We ended up creating a multimedia poem called simply “Forest.”

Forrest wrote the words. I translated/drew them into what you could call a forest alphabet. Each letter of his poem was translated into a seed. When you translate something it forces you to slow down. The act of translation is so tender. It really must be the most intimate form of reading. Each word, each letter, each punctuation mark, carries so much weight in one language—what happens when that is translated?

As the reader scrolls down on the Emergence webpage, the seeds germinate: Forrest’s words sprout and grow into a Redwood forest. Roots reach down; plants and trees reach up. All the little letters form part of the forest community. Groups of seeds—or letters—form trees and flowering plants. They all work together to tell the poem/story, forming a forest. It’s an ecosystem. Everything is connected and supporting everything else.

In my short lifetime, our understanding of trees has shifted dramatically. When I was little, we were taught that trees fight to survive: survival of the fittest. The tallest, strongest trees get the most sunlight and the most nutrients, beating the weaker trees. But science (and scientists like Suzanne Simard and Toby Kiers who are in the book) show us that this is not actually what happens at all. Like human communities, trees work together. Trees communicate with each other, they share nutrients, they protect each other and defend one another. Even in death, they continue to share their love. Dead trees can be home to hundreds, even thousands, of species. Massive, rotted trees collapse into new life. Other plants germinate, sprout, colonize. Fungi and insects move in. The tree will be reborn in so many different ways. I want to die like that.

Like us, trees don’t exist in isolation. We all exist in community, in harmony. We can’t live successfully—we can’t thrive—by fighting each other and stealing from each other. Can we learn from the trees?

Over the years, I’ve made a lot of works using roots. It’s a simple way to show what’s invisible underground. Uprooting our sense of what’s solid and visible and “real.”

I like the simplicity of the forest drawing—it represents a whole community, an ecosystem—as a single entity. That forest organism, for me, also represents our own bodies or even the planet—an organism made up of many different species but acting as one, united.

Katie Holten, “‘Fight Like a Girl,’ Anonymous,” in The Language of Trees.

Could you say a bit about your work with Extinction Rebellion and other groups working in response to the climate emergency and for the “rights of nature" and about the interplay between an artist or writer’s practice and activism?There is a growing realization that modernity and colonialism have led to a catastrophic rupture in the relationship between humans and the world. When I was growing up, I took it for granted that life on our beautiful planet is stable and will continue flourishing forever. Not anymore. We broke it. We are living through the beginnings of the mass extinction event right now.

What to do with the unbearable weight of this knowledge?

My artwork has always been a form of activism—but I never called it that—in the sense that what I do is investigate and ask questions about how the world works and my place in it. It’s an act of learning and sharing. I try to be an active participant in the world around me. For a long time that has meant working quietly as an artist making collaborative artworks. I never called it activism. It was just the work. Today though, we are at a point where it’s too late not to speak out. Silence is complicity. The only way forward, it seems to me, is to join others and try to save everything before it’s too late. We must come together. We can’t do it alone.

As an artist, I resist labeling my work as political. We are always being put into boxes: our work reduced to a cliché. For years, I was the “weed lady” because I worked with weeds. I transplanted weeds, drew weeds, contemplated weeds. Then I was called the “tree lady.”

Narrowing things down like this is the opposite of what I want to do. I want to burst things open. Of course, we need experts and people specializing in fields of study, studying weeds and trees, etc. But, even more vitally, we need to expand our knowledge—we need to blur the edges and merge and overlap disciplines. Life doesn’t happen in straight lines or in boxes.

The Language of Trees invites a breakdown of categories. The book is made up of sections that offer different ways of thinking. It contains poetry, prose, recipes, song lyrics, drawings, science, philosophy, stories, questions, tweets, and secrets. I’ve seen The Language of Trees shelved in Non-Fiction, Nature, Anthologies, Literature, Poetry, and Best of the Underground.

Over the decades, my work has often included community outreach. A few years ago, I cofounded Friends of Ardee Bog, a community-led environmental group.

I grew up on the edge of Ardee Bog. Back in the late nineties, I made some of my first artworks there, a series called Bog Awareness. For years the local County Council and the Irish government were plotting to build a road through peatland in our precious bog. I thought I was the only one who was confused, scared, and angry about these secretive efforts to destroy the landscape. But in 2018 I discovered a neighbor down the road was also upset. The local politicians were moving quickly—creating false statements and undertaking egregious actions on the land—so I suggested to Anne that we create a community group to turn our individual anger into a cohesive movement. Within minutes we came up with the name, Friends of Ardee Bog. Curlews are on the brink of extinction in Ireland. There are Curlews in Ardee Bog, so I drew a Curlew for our logo. That same day I secured the URL and started work on the Friends of Ardee Bog website.

From the beginning, Friends of Ardee Bog was a way for locals to come together and share the beauty of the bog and learn the importance of the ecosystem. It quickly became a resource not only to us living locally, but also on a national and even international level. It’s been shown that peatlands store more carbon than rainforests. People loved learning about the bog. The group grew. I was able to use skills that I’d gathered over the years in public artworks and community activism. It’s all about outreach, sharing information, creating a sense of community, and inspiring hearts and minds. I set up an Instagram account and that’s when things really took off. Social media offers such a powerful way for people to find each other and connect.

Ireland has an amazing group of scientists and citizen scientists sharing a love of peatlands. It was wonderful to discover their work, to learn the importance of our Irish bogs, and to see the explosion of interest in local peatlands. It was inspiring to learn so much so quickly. I grew up at a time when our culture dismissed bogs as dead landscapes, brown smudges on the map to be exploited and dug up and thrown on the fire in the form of turf. All of that has quickly changed in the last few years. The science is now overwhelming. Peatlands are precious habitats. Bogs are not only massive carbon and water sinks, but also vital habitats, home to rare plants, insects, birds, and animals.

My neighbors and I never in our wildest dreams imagined that we would be standing up to politicians in Dublin and taking them to court. But how things have changed! There we were, during the pandemic, dressed in our finest Curlew masks and wellies shouting for justice in the streets outside the Dáil. The bog can’t speak, so we speak for her.

What we were doing is part of a movement of community groups around the world calling for Rights of Nature in order to protect their communities, families, and homes. The precious raised bog is part of our heritage, unique to our little island. It’s home to all kinds of gorgeous creatures like curlews, lapwings, owls, frogs, otters, bog cotton, and carnivorous sundews. If the road goes ahead, they’ll lose their habitat. The curlew habitat has already been destroyed by illegal construction works furtively undertaken by the county council. If we don’t protect the bog, our human homes will also be lost. They’ll be flooded, as will nearby pasture, agricultural land, a golf course, football field, and cement factory. And of course there’s also all the carbon that’s currently stored in the ten-thousand-year-old bog. When the bog is drained it will die and the carbon will be released. Yes, the bog is ten thousand years old, formed when the glaciers retreated after the last ice age. You would think we would have some respect for a precious landscape that has been here long before us. Yet the politicians arrogantly send in diggers to dredge and rip up the land.

Friends of Ardee Bog was created out of a sense of urgency. If we did nothing, the bog would be destroyed by a bypass for a motorway. The road scheme is wrong in so many ways. We had no choice but to speak up and do something. It was inspiring to meet neighbors who were also passionate about our precious local ecosystem.

Extinction Rebellion has been effective at disrupting business as usual and telling the truth. They have woken up a lot of people. XR may annoy some—my mother just wanted to watch Coco Gauff play tennis and other people just want to drive to work—but have you seen the storms? XR disruptions are nothing compared to what is coming. The recent extreme weather events that we’ve all experienced—nothing. We haven’t seen anything yet! The temperature won’t stop at 40 degrees Celsius because that’s too hot for humans—it will keep rising: 50°C, 60°C, and up and up and up.

If you take a few seconds to stop and think about this, it breaks you. And feeling broken and full of despair is not going to help anyone. But you know what does help? Coming together with others who feel just as sick and heartbroken as you do. People power!

Right now in Ireland, the Oireachtas Joint Committee, the only body that has the power to make laws for Ireland, has just submitted its report to the government on the Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss’s recommendations—including the call for a referendum on Rights of Nature in the Irish Constitution. The public is paying close attention. We need to see the recommendations from the Citizens’ Assembly taken seriously. The Oireachtas Committee has recommended that the preparatory steps towards a referendum should begin “within the lifetime of the current Dáil.”

I was invited to share The Language of Trees at the Edinburgh International Book Festival. It was an honor, but overshadowed by the fact that the main sponsor, Baillie Gifford, has billions invested in fossil fuels. Greta Thunberg pulled out when she discovered. I joined with other participants to call on them to divest. The group is now called Fossil Free Books and literary workers are invited to join us in calling on Bailie Gifford to divest.

Most people are sleepwalking into extinction. Extinction Rebellion has helped wake some people from their slumber. We just need a few more people to join and then we’ll hit a tipping point when it will be impossible for the politicians and businessmen to carry on as usual.

NO ART ON A DEAD PLANET.

NO BOOKS ON A DEAD PLANET.

NO MONEY ON A DEAD PLANET.

How to make a difference? How to wake people up? I couldn’t find a way to write stories myself, so I felt compelled to play with the molecules of language itself—peeling the alphabet all the way back to the bare bones. If each letter starts life as a little dot, a seed, what would it grow into? Seeds sprouted, taking root on the blank page as trees. Transforming the alphabet into a collection of trees seemed like a simple way for me to begin my exploration of storytelling. I see it as a gift that I can offer others who want to explore language and how we tell stories.

Can we begin to think outside our human-centered language system, which seems to be causing so much harm? What happens if we offer a space to nonhuman beings within our language system? Trees replace letters, forcing us to slow down and rethink everything. Will this force us to rethink the words that we use? Will it create empathy?

Learning other languages creates empathy. So, I offer a tree alphabet as a gift that will perhaps help some people feel this kinship with nonhumans. Or at least offer a moment to realize that other beings communicate and also have stories to tell, even if we can’t hear or understand them.

All the frustration I was feeling that my work wasn’t having anything like the impact needed meant that I immediately responded to Greta Thunberg’s call to Climate Strike.

I included the Extinction Symbol in my book About Trees. That was 2015, three years before Extinction Rebellion was formed. The Extinction Symbol came first. A circle representing Earth containing an hourglass, it symbolizes that the planet is running out of time. We need more ways to visualize the emergency and share our stories, our hopes and dreams for a better future.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but looking back it seems obvious to me that the buildup to the 2016 election partly inspired the Tree Alphabet. Language and truth were being attacked. It was (and still is) an ugly time. For me, the activism and the artwork are all connected. I can’t separate one from the other because they’re all a part of me. Just like the trees-in-bud inside me. It’s all entangled, like life.

Katie Holten, “Tree Alphabet,” in The Language of Trees, p. xv

Does your new work continue this in any way?

In the last year I have spent so much time with doctors, getting tests, X-rays, CT scans. It feels inevitable that my next project is drawing itself together from all of this living, breathing research into dysautonomia. Looking closely at my own body, at a cellular level, might offer a way for me to think about our global planetary body. I have to learn how to breathe properly again. We all need to learn how to breathe again.

Yesterday I had tests in the “breathing lab” at Mount Sinai. I sat in a glass box, like a vacuum chamber. At one point they cut off the oxygen and I had to keep breathing. Terrifying! Our planet used to have no oxygen. Plants and photosynthesis turned Earth from an inert rock in outer space into a living, breathing ball of life. At some point in the future, if we keep acting the way we are, there may not be enough oxygen for life as we know it.

I’m one of the millions of people with long COVID. Over 70 million people around the world suffer from dysautonomia or another neurological condition. Yet I’d never heard of it before I was diagnosed. Invisible illnesses, hiding in plain sight.

Before I was diagnosed (which took ten months), I started researching the vagus nerve as I had a feeling that was connected to my problems. I made a series of drawings for Emergence Magazine called The Intimacy of Strangers. The title was inspired by Lynn Margulis. It feels like my own body has become a stranger to me. Drawing, by which I mean slowing down and looking closely, can help me understand what’s happening.

My autonomic nervous system is broken. Many of the things that my body should do automatically—regulate my heart rate, breathing, neuronal firing—are all damaged. Standing upright, even just sitting upright, is difficult and can leave me breathless and exhausted. I have to work to regulate my breathing. Luckily the terrifying tachycardia seems to have calmed down, for now!

The CT scans show that I have trees-in-bud. This is an actual medical term. Can you believe it! My own body is teeming with budding trees. This is my next drawing project.

I’m looking back at the drawings that I made for Emergence Magazine’s latest issue, Shifting Landscape, which looks at Migration. I explore cellular migration and relationships happening within my own body at a teeny tiny-scale, which (of course!) mirrors migrations and patterns happening at all kinds of different scales in the universe. Self-similar patterns repeating. Now that I have a break from the book tour and I have my trees-in-bud diagnosis, it’s time for me to sit down and look closely at my inner trees. Looping us back to the beginning, again!