Eventually, I was able to hold some of Ong’s star chart poems in my own hands and explore her first book of visual poetry, Silent Anatomies, chosen by Joy Harjo for the Kore Press First Book Award, as well as the recent anthology from Fonograf Press, A Mouth Holds Many Things: A De-Canon Hybrid-Literary Collection. With each encounter, my fascination for her innovative work has grown.

Now, just before the release of her second book, Planetaria, I had the chance to correspond with Monica Ong about her profound, multifarious, and dazzling visual poetry practice.

Your first book, Silent Anatomies, frequently engages with science through medicine and anatomy, using medicine bottles and anatomical drawings, for example, and in your new collection, Planetaria—works from which also take the form of stand alone artist-books, exhibition, and more—you draw on astronomy. I noticed one of your visual poems even appeared in Scientific American. I’m curious about how you developed an interest in writing poetry related to science, and specifically, how your new work came to focus on astronomy?

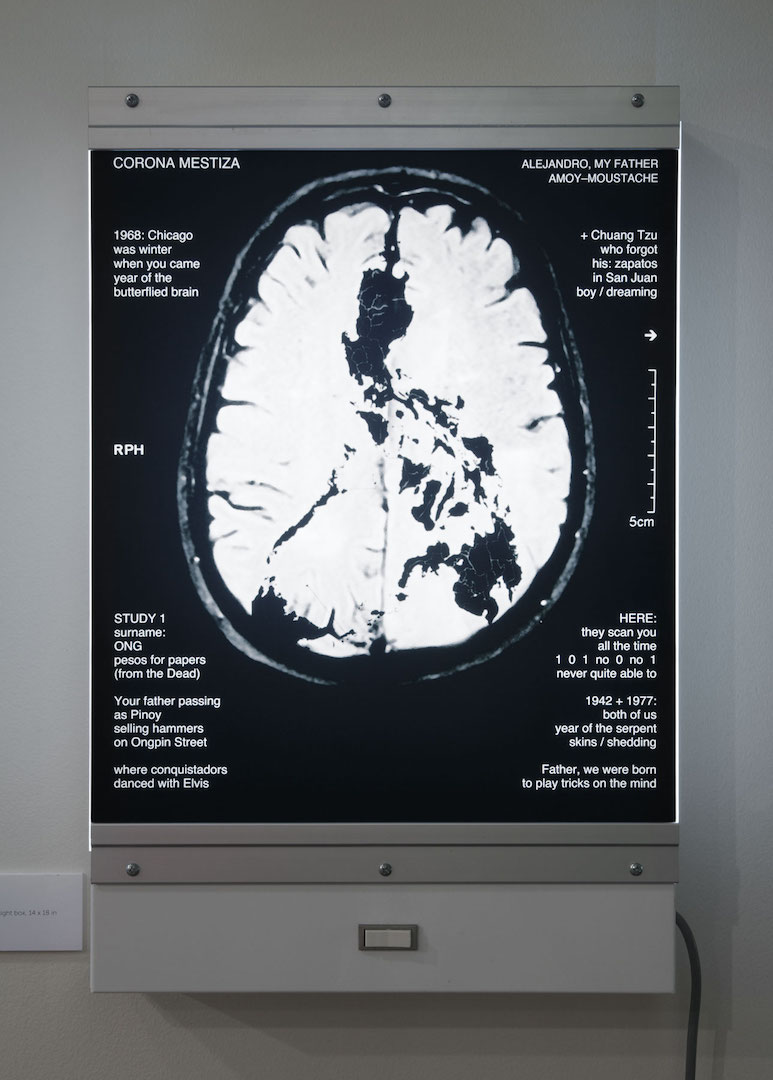

As the daughter of a physician, I often found myself surrounded by medical journals and books scattered around the house. They were full of language that felt authoritative and familiar yet undecipherable and at times intimidating, which carries a lot of parallels with my own understanding of my parents’ histories. The medical ephemera became an entry point to go deeper into my family’s medical-emotional landscape but also offered an opportunity to experiment with making poems that did not necessarily rely on linearity or conventional poetic forms. There’s also something about making a poem into an x-ray chart or medical object where you give readers an opportunity to slow down and do a closer, more exploratory reading.

Corona Mestiza. Monica Ong. Duratrans print on vintage medical light box. 14” x 18” x 4”. Photo documentation by Steffen Allen. Collection of American Literature, Yale Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

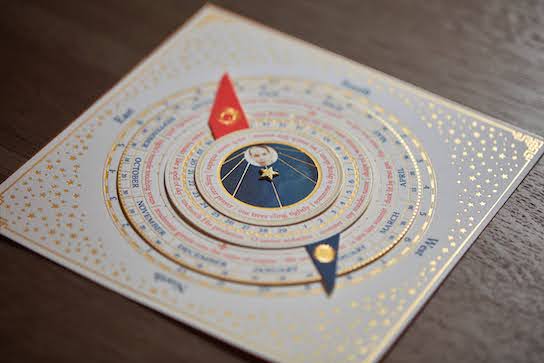

The designer in me tends to follow certain impulses too. I often walk by things that grab my eye and say to myself, “I don’t know how, but I want to make that into a poem.” That was exactly what I felt when I saw a planisphere for the first time. I loved the idea of not only seeing how the stars appear on an auspicious day, but also being able to see a poem revealed in the map.While my investigation of medical ephemera focused my gaze on deeply personal histories, I think the visual language of astronomy gave me a chance to extend my gaze towards imagining potential futures and spaces of belonging. To be honest, I needed a way to zoom back and take a broader view so as not to be pulled down by the weight of the ongoing turmoil we’ve been navigating in this country this past decade. I spent a lot of time looking at vintage science textbooks as well as early medieval volvelles, asking questions like “What would it mean to create an imagined textbook as a map to navigating this messy experience of working motherhood?” or “How do you write an interactive poem that changes with the moon’s phases as well as with each reader?”

The epigraph for Silent Anatomies, “I wish I could tenderly lift from the dark side of history, voices that are anonymous, slighted—inarticulate,” by Susan Howe, feels in some ways relevant to the work in Planetaria, too. Could you talk about your research into the work of women in science, and how your process of research-creation fed into your creation of the poem “Her Gaze,” which you created as a ViewMaster reel (images of and from which are included in the new book, Planetaria)?

The epigraph speaks to stories that can tend to be overlooked or hidden from the collective gaze. With Planetaria, I wanted to utilize the visual language of astronomy, a historically “male” space, to take a closer look at the stories of women’s labor. I also saw connections between people who were the “firsts” of their family or gender venturing into a new space, even if it meant defying tradition or the social constraints of their time. Whether it is a female scientist or my family’s migration to a new country or deeply personal struggles with working motherhood, I am often wondering what it takes to shift the gaze we inherited towards something more generous and holistic.

I learned about Caroline Herschel while listening to a women’s history podcast. I was really struck by the tenacity and stand-alone spirit of Caroline Herschel’s incredible life and instinctively felt compelled to frame a poem about her with the sketches she made of her discovery of the Comet C/1786 P1. The poem is designed in the form of a Viewmaster reel to invite the reader to take the stance of stargazing when pointing it up to the light, but also comes from this need to remind myself of the importance of looking up at the sky (and not down at the phone) to maintain our personal connection with the cosmos. By framing the poem that way, the reading of the work also trains the reader’s gaze upon evidence of her labor and how she saw the sky, while also positioning her biography as a critique of the male gaze. What’s so great about Caroline is that she cultivated greatness on her own terms.

Her Gaze: In Tribute to Caroline Herschel. Monica Ong. Custom ViewMaster reel. 4” x 4”. Courtesy of the artist.

In all of Planetaria, the presence of the sky, the stars and moon, give a broad context for the human considerations in the book--migration, motherhood, women in science. I’ve listened to an episode of the buddhability podcast in which you discuss the influence of Buddhist practice on your creative process. And I’ve noticed a connection between the astronomical focus and a buddhist perspective on impermanence and cosmic scale. For example, in “Feather,” you write: “Take comfort in knowing that this year is but a blink in the breath of trees and cosmic moss, that the nebulae with all their dust hardly noticed how the phone slowly died, how you burned the maps to your forefathers’ graves.” Finally, I thought about Alejandro Zambra’s words, “Every story, every poem, every written piece is about belonging,” and wanted to ask whether there is a connection in your work between the practice of Buddhism, this astronomical scale, and questions of belonging related to gender, migration, and diaspora?What a really profound and thoughtful question, Heather. Thank you so much for asking. I think the thread that connects my Buddhist practice to the cosmos and diaspora is this cultivation of a personal gaze that can see past the transient moments in which we encounter each other and instead opt for a more embracing long-range view that is rooted in the belief that we are more deeply connected than we think. What we think we know about someone or something is never the whole story and it’s important to leave room for surprise or a shift in perspective. Scientific “laws” are being overturned all the time with the evidence from new discoveries, as the physicist Chien-Shiung Wu demonstrated. What both Buddhists and scientists do that I love is to lead with questions and to experiment with a sense of adventure. In this spirit, I am grateful to my parents of Chinese diaspora who were the cosmonauts in my life, migrating from the Philippines to the unknown United States to build a place of belonging and home for me and my siblings—and as all is connected, I credit them for planting the seeds of this book by taking that risk.

Embracing transience allows me to loosen my grip on fixed rules or expectations built into our identities—it allows space for expansion. What I learned from my family is that notions of identity and home are quite porous and ever-evolving, and that even the most authoritative “textbooks” are really just the best guess one can make at any given moment of time. Likewise, my parents did the best they could with whatever was available to them and nowadays I am the one fumbling along as an artist mother trying to find something solid to stand on in a messy world. What I find useful is that Buddhahood is a state that’s inherent in everything if we can train our gaze to see it. The daily practice of chanting Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo helps me dig deep for the wisdom to create value from whatever is happening and to “change poison into medicine,” especially in the midst of the problems and relationships that challenge us the most. But in order to do that we need to let go of our attachment to judgement or the need to be right, and instead choose to focus our efforts in service to something larger than ourselves.

I have to ask about your phenomenal volvelles, which, perhaps more than any of your other works, have dazzled me with the complexity and non-linearity of the poetry and the precision and delicate mysteries of their material forms. Both The Star Gazer and Lunar Volvelle generate different possible poems based on the rotation of the discs, and in your book, you situate the images of each volvelle next to one possible reading of each, a full moon reading for the Lunar Volvelle and March 4th, the birthday of artist-poet Theresa Hak Kyung Cha for The Star Gazer. The latter begins “You are here / to enter the palace of your life / to meet yourself / on the side of the road / arms waving / beneath a tender sky.” I’m curious to know how you conceived of these poems, wrote and created the objects themselves, and how you’ve seen people connect and interact with them.

I really enjoyed making these poems not only to experiment with the literary possibilities but also because I loved the challenge of designing works in this form after seeing many gorgeous examples in medieval manuscripts. While the star chart for The Star Gazer traditionally seats the Great Emperor of Heaven at the center of the night sky, I wanted to center the reader instead by using the familiar marker “You are here,” and reversing the cosmological hierarchy of the chart, if you will. I spent at least six months outlining the 263 asterisms in the chart based on the etching of the Soochow Astronomical Chart of 1193. After selecting the names of asterisms to highlight, I wrote original verses to create connections between stars and then made mockups with the advice from a historian of Chinese astral sciences who helped me orient the chart in the right cardinal direction. Once all the files were designed, I worked w/ a letterpress studio (Boxcar Press) to print the piece in gold foil. Altogether, The Star Gazer took at least one year to fully realize.

The Star Gazer: Planisphere Poetry. Monica Ong. Artist Book. Letterpress gold foil stamping on natural white and navy cover stock, custom die cutting, and assembly with metal hardware, 7.6” x 7.6”. Photo documentation by Tom Virgin.

You’ve chosen to publish Planetaria with your own imprint, Proxima Vera, through which you’ve also published artist books and broadsides. I’m curious about why you made that decision, as opposed to publishing with an extant poetry or art press. This intrigued me, because I know in the world of artist books, an artist imprint is a common practice, and in the world of poetry, it’s more rare, though not unheard of. I wondered if this was necessary for you to have creative control over the production values, or whether there were other factors at play, like a desire to contextualize this work in a certain field?What I learned over the years of making visual poetry is that a visual poet cannot only be concerned with what is on the page but also needs to consider the systems and processes involved in making and sharing the work as well. There are many publishing models that come with varying sets of goals and limitations, benefits and drawbacks. For my work, design is not something that is hired into the process after a manuscript is submitted, but is actually an inherent part of a poem’s conception and as such not something that can be outsourced. I acknowledge that my perspective is unique to being a designer who has spent two decades already accustomed to working with vendors, directing photography, producing digital design, and managing production schedules.

When I started considering how to make my fine press poems, it became clear that if I wanted to see them through to the vision I intended then I would need to be in the position to oversee the production process. That provided the initial impetus towards founding the micropress and getting to know the work of book artists at fairs like Codex. It was deeply inspiring and refreshing to see how radically the book form can be re-imagined and to expand the channels for one’s literary practice to encompass exhibitions, fairs, and “gatherings” as touchpoints for readers. My world really shifted after meeting book artists like Julie Chen who founded Flying Fish Press, the incredible design phenom and book artist Thad Higa, and paper engineer Colette Fu.

Once my editioned pieces began finding their way into institutional collections and exhibitions, I was warmly encouraged by fellow writers and colleagues to see what my designer’s eye could bring to the book production process. The time I’d already spent exploring traditional pathways was going nowhere so I decided to go all in to learn and trust the process of building my own imprint. And you’re right to suggest my alignment with a certain cultural context because I often turn to the Fluxus-era avant gardes who started their own presses and book movements, like intermedia artist Dick Higgins who founded Somewhere Else Press, poet/artist Ulises Carrión who founded Other Books and So and even created a shadow postal system for mail artists, as well as poet/typographer Philip Gallo, who founded the Hermetic Press. I also look up to the community engagement and political activism that is central to the contemporary practices of artist/printer/designers like Ben Blount, Corita Kent, and Amos Paul Kennedy, Jr.

What I learn from them is the importance of remembering that if you do not see an infrastructure that already exists to support your work, then it will be imperative to include systems building into your practice so that you can pave new pathways not only for your own innovation but as a way to gather with like-minded community. Look, the Cinderella era in publishing is over. Stop waiting for your lottery ticket and wishing your prince will come because they won’t, especially the further you venture out of genre conventions. It has always been a fact that experimental artists have had to create their own presses, channels, economies, gatherings, and systems anyway. No one will be more invested in your risk-taking than you. So it is worthwhile to have an entrepreneurial spirit and figure out how to build networks and infrastructures that let you invest in your own vision.

Planetaria (Book Cover). Monica Ong. Proxima Vera, 2025. Courtesy of the artist.

I’m curious about your use of family photographs, which are used in both of your books and featured in many of the most poignant pages of Planetaria. Could you talk about the process of one of the works you’ve made using a family photo, and whether the piece began with that image or whether you made the connection later?Looking at archival family photographs is in many ways like looking at stars: you’re time traveling, observing etchings of light that came from moments and places in time that once were but are no longer with us. When I make works with photographs, I don’t adhere to any routine methods at all but instead spend lots of time looking at things and noticing any interesting connections between them. For Solstice Blessing, I was fascinated by a surreal illustration of Saturn that looked as though it had fallen into the water with its rings submerged. There was also another diagram trying to illustrate the varying distances between earth and other planetary objects. While walking through a flea market, I then came upon some vintage wood drawers that I thought might make an interesting frame for the poem if I printed the poems on acrylic and then put some lighting inside the box behind the stars. But I needed something to anchor the poem. Finally, I came upon a photo of my mother sitting by the water looking out into the distance. I wondered what she was seeking in the distance and I also thought about the distances that exist between mothers and daughters. I played with these elements and added stars to accentuate her profile until I had a visual setup for the writing. From there I wrote Solstice Blessing and scaled it to a size that would be legible as a light box. The visual poem worked as a fold-out in POETRY magazine and has been exhibited in the gallery as both a light box sculpture and also a window installation. Each one provided design challenges for me to optimize the reading and visual impact in the space. What I loved most was being able to walk into the gallery with my mother and show her what she inspired in me.

Interior view of Monica Ong: Planetaria exhibition at the Poetry Foundation gallery, April 21–September 8, 2022, Chicago, Illinois. Photo documentation by m_m<M.

In a conversation in Bomb magazine, you say, “I like to think that hybrid practice equips us to live beyond binary thinking. What emerges when working ‘between’ disparate polarities is that third space, something broader and more generous that aspires towards a design that can hold us all.” You also quote Ben Shahn, saying: “Form is the very shape of content.” How have new forms have emerged from your ideas, or vice versa? Have you innovated by necessity, by design, or both? I know this is a bit abstract, but I’m very curious about the particulars of your process, because your art, craft, and writing seem inextricably connected.This idea of living and making from the third space really just comes from being a daughter of diaspora, someone who is always translating between my parents’ worlds and the places we navigate together, of someone who is often operating between disparate poles of identity, and who practices writing in an art studio. It’s an improvisational way of being and it allows you to see possibilities in things that you don’t expect. When I make a new piece, I’m also looking for affordances that create a welcoming sense of invitation for readers to enter just as they are.

Sometimes I’ll start in the Most Dangerous Writing App and just let the writing flow. Whatever I yield is raw content that I start with and that leads me where it wants me to go. If there are images, maps, or objects that it points to, I try to sniff out those clues and follow them to archives or randomly related places. The writing will usually open my third eye to start paying attention to forms and surfaces I might not otherwise consider. I try to remember that I am here to serve the work and to let it tell me where to go and what it needs. I love when it leads me to do a great deal of looking: in flea markets, Chinatowns, old bookstores, restaurants, obscure museums, tattoo parlors, gardens, as they all offer very interesting interfaces for reading. If I’m lucky, I’ll see something that calls to me to bring all these elements together into a new experience of poetry. This moves into a stage of sketching and making. I might be trying a new layout in InDesign or cutting up paper to see how large to scale something. Prototyping is messy but once I start seeing what is emerging, I then focus on iterating and refining towards the final form, thinking always where and how it will be read and what the interaction with the reader is usually like. It’s like writing, design thinking, and production converging at the same time. Some poems might take a week and others over one year to manifest. It’s like gardening though, you create the causes and conditions and then let each world bloom when they are ready.

Monica Ong. Portrait by Matthew Fried. Courtesy of the artist.