In the following interview, Federici and I began our conversation on his career beginnings. We discuss the intersection of linguistics and physics, the structures of different languages in his practice, how asemic writing reconfigures meaning and the reception of meaning, and John Cage, one of his biggest artistic influences.

Before becoming a visual poet and artist, you had a background in physics. What made you dive into the world of poetry and visual art?

My transition from physics to visual art was not a departure but rather an expansion of inquiry.

Physics and, on a different yet not contrasting side, writing are studies of structures, of underlying rules governing systems that often remain invisible to immediate perception. Visual art and, specifically, the twist of writing toward its purely visual perception, allow for the investigation of structures and the metric relations between them: not only those that govern physical or textual phenomena but also those that shape, at its core, language, cognition, and perception. The shift gradually occurred as I started to recognise a certain limitation in the conventional symbolic approach at the core of representation in both physics and literature. Equations and written texts do capture relationships, but they often lack or are too sharp in marking the boundary between the experiential and the theoretical aspects of knowing. For, what is a sign? What is a particle?

The commonly shared idea of an elementary particle is that of a small volume of space in which a certain amount of energy is confined, eventually with no further substructures, or at least, none immediately available. But what does it mean when a particle behaves as a wave? A particle does not dissolve into waves, nor does it do so before recombining back into a particle. I found this dynamic comparable to that of the signification of a word dissolved into writing. Writing becomes a creative, process-driven device, blurring the essence of signs, while attempting to focus on and capture their essence and the reason why.

In exploring these limits of formal systems, I turned to asemic writing as a set of methods to test how meaning emerges and dissolves in the combined act of writing and interpreting. My early engagement with experimental literature provided a preliminary conceptual framework for this transition. What I sought was not a rejection of scientific reasoning but an extension of its methodologies into domains where ambiguity, rupture, and non-linearity were central. The aesthetic and, in a sense, the ethical dimension of meaning-making became my new field of research.

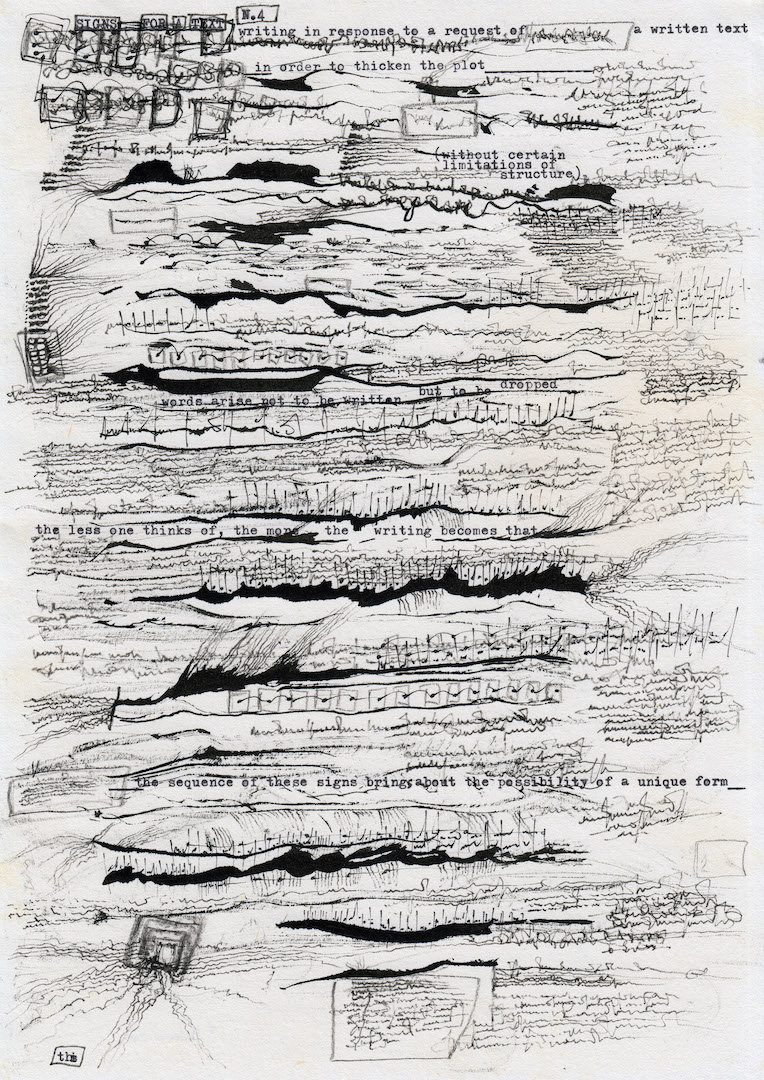

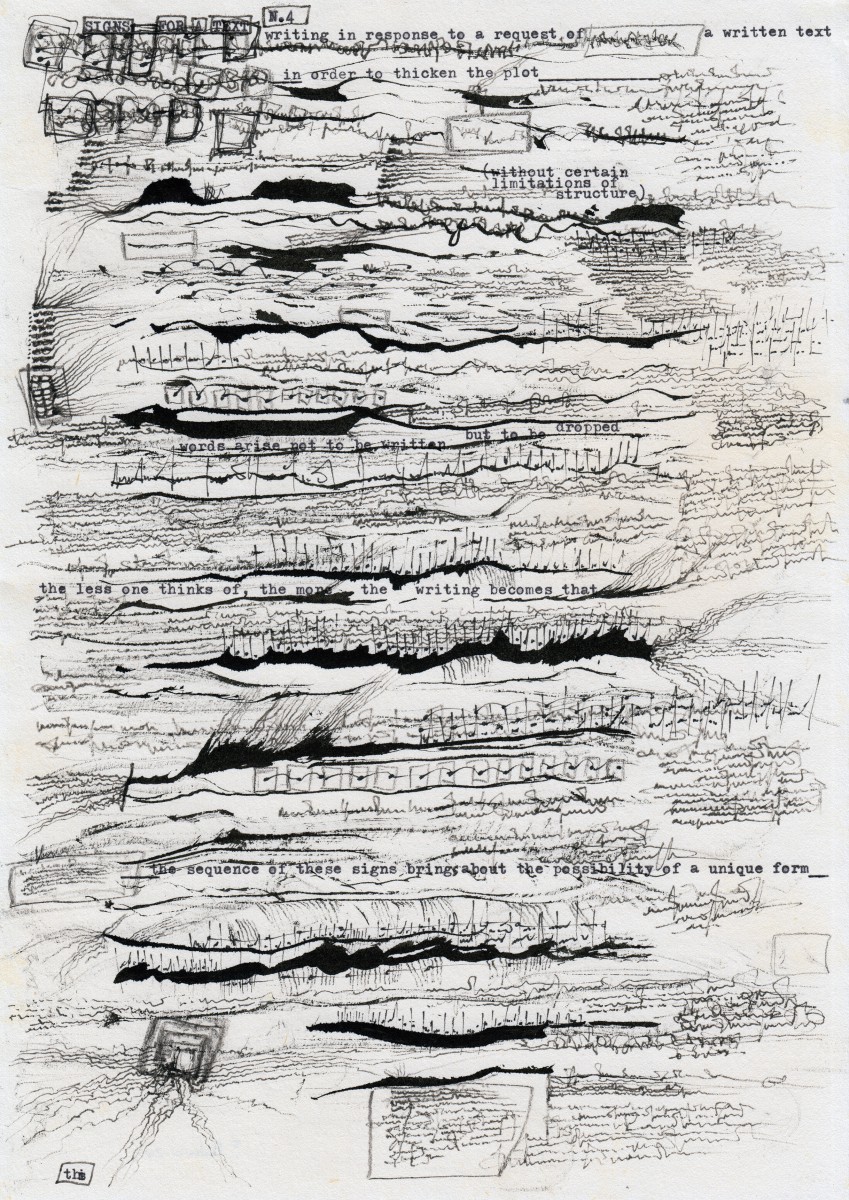

Your poetry and your expertise in physics and mathematics are connected. In “Writing in Response to a Request of a Written Text,” for example, you relied on Fourier analysis to trace the frequencies and phases to determine the relationship between text and words which, on your canvas, turns increasingly fragmented. Could you tell us more about your practice in general? Could you point us to another of your visual works and discuss its connection to quantum mechanics or another area of physics?

My practice involves the intersection of linguistic structures and mathematical formalisms of physics, where text is not the ultimate medium of meaning but an active topological object, a field of signification constantly modified by other signs scattered in it and into which those signs interact and be transformed.

In “Writing in Response to a Request of a Written Text,” the Fourier analysis serves as a methodological background to suggest how the deconstruction of the apparent linearity of the text as signal reveals underlying frequencies, i.e., signification threads, that inform its structure. This becomes particularly insightful when dealing with noisy textual blocks (not only randomised ones but also stereotyped models from colloquial or mainstream information exchange). Provided that they are filtered, decomposed, erased, and reframed with the help of or within signification-open processes of writing, mediated by sensors or computer-driven routines, a multiplicity of components, seemingly unrelated to the original content, may be activated.

Writing in Response to a Request of a Written Text: pencil, ink, pigment liner, Olivetti Studio 46 on 210×295 mm semi-rough sheet, 2024 (Rome, private collection). First appeared on «LandArch», London, September 11, 2024.

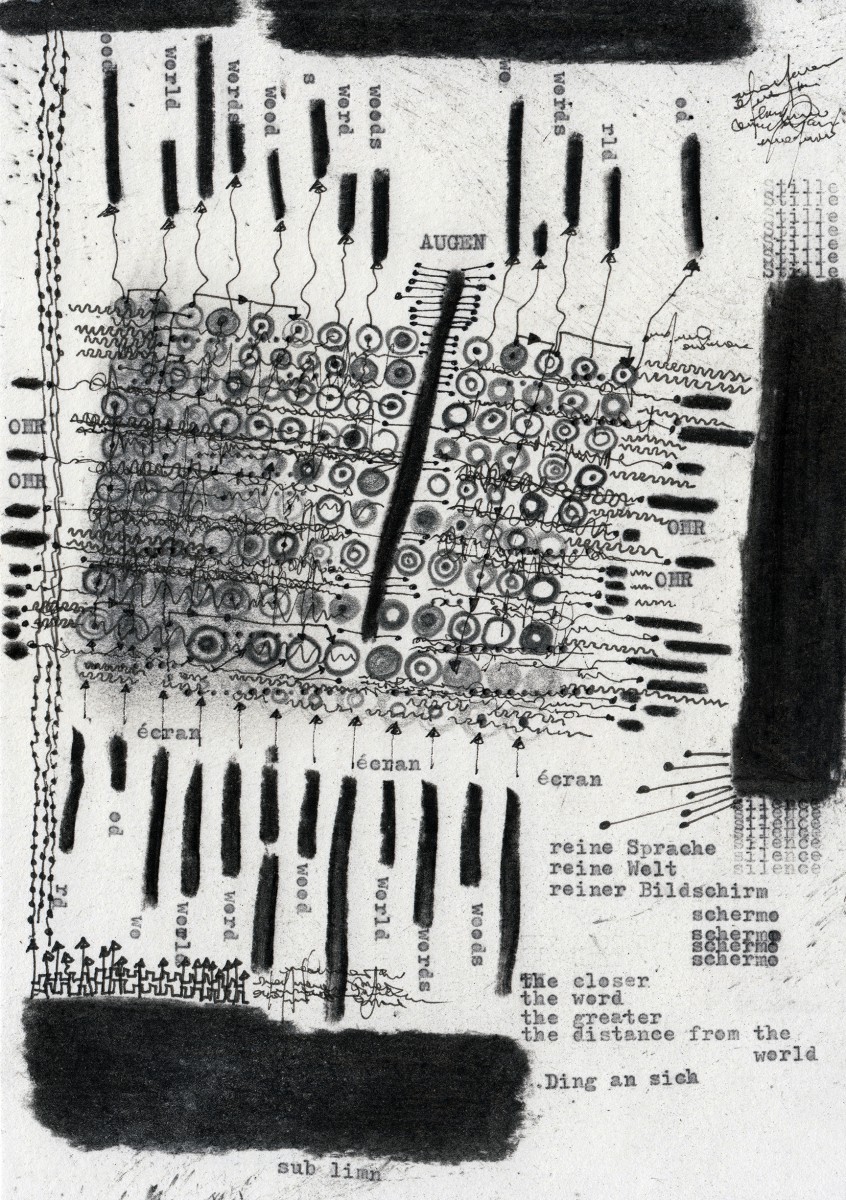

Another work that reflects an analogous connection to the field of biophysics is “Ding an Sich,” which is from the Transcript from Demagnetized Tapes catalogue. The body of the text is here addressed as a neural-semiotic network composed of cells, synapses, and various receptors or attractors. Sensory organs—suggested by the matrix of terms “Augen, Ohr–Ohr, écran,” or “eyes, ears, and skin”—function as interfaces that attempt to gather stimuli from the “Ding an Sich” substrate. Similarly, the artificial fuzzy and neural networks designed on the same page suggest adaptive mathematical models shaping their internal states in response to alleged incoming data.In biological systems, the initial configuration of a cognitive or perceptual device is continually reshaped by the flux of language and information. However, the pace of learning often lags behind the fluidity of perception. A word can thus be seen as a collection of alphabetic shells, representing unstable states subject to fluctuation. It is always ahead of its fully internalized signification. The transformation from “world to wor[]d” illustrates this fragmentation, where letters, much like charged particles, interact through processes akin to electrostatic charging and discharging.

To signify is to exert a certain friction, a resistance that shapes meaning. Language, in its tendency to even conceptualize potential errors, extends beyond mere representation, moving toward abstraction. However, an excess of information—the surplus generated by language’s divergence toward abstraction—complicates the predictability of textual trajectories. Even when a text is structured by minimal sense attractors, asemic deviations persist, reinforcing the instability of interpretation. This approach is further analysed and expanded in my forthcoming book I(c)onic Log (Calamari, 2025).

Ding an sich, charcoal, pigment liner, Olivetti Studio 46 on 148×210 mm semi-rough sheet, 2019.

You’re an Italian artist, and your work draws on multiple languages in addition to Italian, including French, German, and English. What does each of these languages mean to you in your creative process, and how do they impact how you approach your visual work?Each language I engage with carries its own structural constraints and affordances, which influence how I manipulate text in visual works. My native language, with its deep sonic and rhythmic foundation, has probably shaped my sensitivity to phonetics and cadence.

French offers a playfulness with syntactic and morphological fluidity that enhances certain forms of experimentation, particularly in the domain of sound semiotics. Its tolerance for elision, liaison, and homophonic ambiguity creates an implicit layering of phonetic and semantic possibilities, making it especially conducive to explorations of signification through sound. Moreover, the relatively fixed word order but flexible pronominal and reflexive constructions constantly recalibrate the subject-object relationships in ways that resonate with auditory perception. The prevalence of nasal vowels, silent letters, and liaison effects generates a field of indeterminacy where phonemes can slip into one another, destabilizing fixed units of meaning. This phonetic malleability provides a unique medium for experimenting with how signification is carried, distorted, or refracted through sound.

From a theoretical standpoint, these linguistic properties align with certain aspects of acoustic semiotics, where signification emerges through differential relations within a sonic field. The polysemic nature of many French words, combined with their phonological particularities, fosters an interplay between phonetics and semantics that can be actively mobilized in research on how auditory elements influence the perception and generation of meaning beyond purely lexical structures.

German, with its extensive use of compounding and conceptually precise structures, paves the way for elaborate syntactic constructs by fusing multiple morphemes into single lexical units and creating highly specialized terms that encapsulate complex relationships in a single word. This enables a condensation of meaning that is particularly valuable in sound semiotics, where nuances of articulation, rhythm, and phonetic layering require precision. Additionally, its system of case-marking and word order flexibility allows for variations in emphasis and relational dynamics that are less accessible in more rigid syntactic systems. The strong phonological presence of consonant clusters and long vowel articulations contributes to a distinctive auditory texture, reinforcing the interplay between phonetics and meaning construction. In this sense, German facilitates a meticulous dissection of how sound not only conveys but also structurally determines semantic and semiotic formations.

English, often valued for its ostensibly neutral and polished syntax, operates as a bridge language in contemporary discourse, establishing a plain yet effective level of abstraction and economy. Its analytic structure, characterized by a lack of extensive inflection and a preference for word order over morphological marking, enables a streamlined syntactic framework that lends itself to precision and clarity. Its simplicity sharpens the juxtapositions between visual and textual elements and creates a space where sound and meaning can be deconstructed with minimal syntactic interference. Furthermore, English’s global reach and adaptability reinforce its role as a mediating language in semiotic research, particularly in multimodal contexts where linguistic and extralinguistic signs interact. Its openness to lexical borrowing and hybrid formations also fosters flexibility in sound, where shifts in pronunciation, stress, and intonation patterns introduce subtle but impactful variations in meaning. As such, English does not merely function as a neutral conduit but drives the process of writing with its structural minimalism and capacity for translingual engagement.

These linguistic differences inform how text is fragmented, layered, or erased. Thus, multilingualism is not merely a thematic concern but a material one: it determines how letters interact and how they dissolve into or resist the surrounding space. Language becomes both an instrument of meaning and a medium of disruption.

In a visual poem, space extends beyond the visual, just as time is not confined to rhythm. Its layout functions as a structured language grid.

Code-switching emerges instead as an external, more abstract method of analysis, emphasizing classification over social context. It is particularly suited to linguistic variations that serve as tools for exploring a non-human, phenomenal reality—perhaps even language itself. At the level of signifiers, it operates like a measurement tool: a clock signifies time yet time transcends it, much as a text may generate signification rather than merely conveying meaning.

From a visual standpoint, juxtaposed multilingual segments disrupt interpretation whenever they are approached from the perspective of a single language—whether one of the juxtaposed languages or another in which those segments are often translated innately. Gaps between languages are filled through simultaneous translation or associative reasoning, yet signifier analogies fail to resolve the intrinsic dualism. Grammatical gender, phonetic patterns, and visual rhythm all shape perception and the process of signification.

These segments create an unresolved interpretive tension: visual patterns propagate through nested or perhaps even hidden linguistic layers, edging toward a fixed signified-signifier equivalence. This instability parallels simulated annealing in neural networks, where an initial arbitrary state undergoes refinement through iterative adjustments. Just as neural networks employ reward/penalty mechanisms to reinforce certain pathways while discarding others, the act of reading across multiple languages filters possible interpretations, privileging some while marginalizing others. Yet, to prevent premature stabilization within a single linguistic or cultural paradigm—analogous to getting stuck in a local minimum—stochastic noise must be introduced. This corresponds to the reader’s exposure to linguistic estrangement, the reshuffling of familiar conventions, and the necessity of navigating associative rather than strictly translational logic. In this way, signification remains dynamic, resisting the constraints of monolingual determinacy.

In your work, it seems there’s always an opposition of stillness—grounded by the building blocks of words—and chaos, manifested in the unruly lines, dots, and cursive. The text appears to respond to the more “visual” elements that complement it, and vice versa. Could you speak more about the complex ties between words and, for lack of a better word, illustrations? Do they function as mutual abstractions?

The relationship between text and visual elements is never one of illustration but of tension. Words, though often seen as stable carriers of meaning, are in constant flux when subjected to visual transformations. The act of writing generates movement—a gesture that destabilizes the fixity of language. Conversely, visual marks, often perceived as expressive rather than semantic, take on structural roles, delimiting, interrupting, or reorganizing textual space.

Words and visual elements act as mutual abstractions: the text gestures toward an unspeakable form, while the visual marks suggest a latent semantic charge. Semantised and asemic signs, depending on the scale on which they are perceived, undergo transformations. This may recall quantum dualism or echo the models where certain physical elements determine the metrical properties of space.

Artworks engage with legibility as an observer-dependent phenomenon, much like how measurement in quantum mechanics collapses a probability wave into a definite state. My approach attempts to bridge the precise and the indeterminate, to test the limits of what can be structured and what resists formalisation.

Your art challenges and expands the concept of what language can do and reveals the instances in which it fails. What is your conception of language? How did you get to your present asemic work?

Just as the geometry of the universe in modern physics is not merely a mathematical construct—as it must reconcile abstract models with empirical observation—languages are not purely linguistic constructs. Their boundaries are not determined solely by internal linguistic structures but are shaped by extralinguistic factors such as historical developments, sociopolitical forces, communicative demands, cognitive limitations, and evolving semiotic practices. This distinction, much like the delineation of geometric spaces, is not an intrinsic property of the system itself but rather a consequence of the parameters imposed upon it.

As such, language is not a closed, self-referential system but a contingent structure that unfolds through interaction and interpretation, something negotiated, incomplete, and always slipping beyond its own articulation. It is both a structuring force and a site of instability, subject to shifts in context, reception, and use.

My approach has thus never been one of mere communication. With these premises, asemic writing naturally emerged in my practice as I sought to move beyond the assumption that signification is pre-existing, encoded by the writer and recovered by a reader, and that the act of writing not only records meaning but also generates it. I was drawn to the threshold where writing destabilizes itself, where the structure of language remains but its immediate legibility dissolves. This interest aligns with my background in physics and mathematics, where systems may display chaotic behaviour, emergent patterns, and nonlinear transformations. Asemic writing investigates this instability. It does not abandon language but pushes it to the point where its signifying function becomes self-referential. It determines a continuous oscillation between recognition and abstraction, between the moment of signification and the point at which signification fails or shifts. This trajectory also shaped my engagement with multilingualism, where the boundaries between languages function as fault lines of meaning.

One characteristic of asemic writing is its open-endedness: eluding linguistic conventions or producing a vacuum of meaning, it leaves its interpretive agency in the hands of the readers and beholders. How do you situate your work in relation to your audience? Do you consider your engagement a collaboration?

In the last couple of years, I have started conceiving asemic writing as a form of translanguaging that operates between codified languages and archetypal systems of signs, where the signifier continues its search for meaning through unstable variants. This drive towards reconnection generates the linguistic tension inherent in the asemic page. What, then, does reading activate in the brain?

Asemic writing revives a pre-linguistic mode of imitative drawing, abandoned in favour of a structured, legible script. Over time, handwriting has conditioned an unconscious inheritance of signs, where the division between signifier and signified remains unresolved. This practice acts as a natural multiplier of noisy variants of a signal, perhaps a form of sabotage of an initial message, which results in a text that perpetually reconfigures itself, subsuming real and imagined languages alike. In this sense, asemic writing functions as a signal subjected to recursive interference, where, unlike what happens in communication theory, noise is not a component degrading the integrity of the message, but a creative principle. Language noise, i.e. the instability of fixed and mentally framed signs, proliferates into structures or, even better, is an intrinsic trait of those very structures.

Transcripts from Demagnetized Tapes (LN, 2021) is a work entirely dedicated to exploring this multiplication of variants and reconfiguration: signification does not appear to reside in any original and final form but always emerges through a form of corruption. When a tape is demagnetized, the recorded signal is not erased but transformed into a residual field of traces—partial imprints of what was, now dispersed into indistinct layers of interference. Similarly, asemic writing destabilizes the notion of an ‘initial message’ by allowing its own signifying elements to mutate, fragment, and recombine. It enacts a form of sabotage not as destruction, but as a deliberate subversion of a message’s presumed fixity, which is precisely the same idea as that of a particle existing in a superposition of states, of the wave-particle dualism, or the concept of uncertainty behind Heisenberg’s principle.

The ‘multiplier’ aspect is crucial: each iteration of noise does not degrade the original but spawns alternative paths of signification. As in magnetic tapes, the result is not a void but an accumulation of possible readings—palimpsestic, layered, and unstable. The text, therefore, remains in a flux, perpetually reconfiguring itself, referencing existing linguistic systems but also absorbing speculative, forgotten, or non-existent languages. It allows for the coexistence of these multiple interpretative layers, where known alphabets dissolve into gestural marks, and hypothetical scripts emerge as legitimate textual presences, as a perpetual oscillation between sense and non-sense, recognition and alienation, destabilizing the boundary between language and its absence.

I still recall the day when the idea of using old partially demagnetized tapes as a metaphor for asemic writing first came into my mind. I had just discovered, in an old box of family memorabilia, a rustling tape with the voice of my father recorded on it while reading a poem to my mother. The fact that he is no longer here, yet his voice remains—still alive but biologically detached—manifested as a liminal trace at the threshold of linguistic signification.

The generation, or rather, the germination of meaning unfolds through both conscious and unconscious processes. Asemic texts create a horizon of expectations within forms seemingly devoid of content, where the outcome depends on the reader, much like quantum measurements depend on the experimental setup. Here, multiple modes of readership and authorship become inseparable.

Does meaning reside within the text, or is signification activated from a range of possibilities upon reading? If the latter turns out to be true, then what is transformed into content? This may seem like a shift in the problem, but it is not entirely so. Just as all phenomena involve energy exchanges, so does a text, upon each reading, trigger a release or accumulation of signification. In this sense, the processes of measurement and meaning-making may be described in parallel terms.

Interpretation is not an external process imposed upon a text but something that emerges through the encounter between the text and the reader. In asemic writing, this encounter is heightened because the usual mechanisms of linguistic decoding are suspended or disrupted. My work does not dictate a single reading, nor does it rely on a fixed semantic content to be retrieved; instead, it establishes a field of potential meanings, where the act of perception plays a constitutive role.

This does not mean, however, that my engagement with the audience is entirely open-ended or passive. The structure of a work—its composition, its use of rhythm, density, and contrast—creates vectors of signification that guide the interpretive process, even if it does not determine it outright. In this sense, my approach is neither didactic nor arbitrary, but one that seeks to shape the conditions of reading while allowing space for the reader’s own cognitive and sensory engagement.

I do consider this a form of collaboration, but not in the conventional sense of co-authorship. Rather, it is a collaboration with the act of reading itself or, in other words, how a reader’s expectations, habits, and perceptual patterns interact with the text. The work is not complete without this act of reading. Meanwhile, the work’s asemic dimension ensures that its meaning remains in flux, permanently contingent upon the moment of encounter.

Your work seems to draw heavily and also playfully on the field of semiotics. How does your sense of semiotics guide you, once you have an inspiration, toward sound art, asemic writing, visual poetry, or another medium? Or do you often start with form?

My engagement with semiotics is not strictly theoretical, but rather a way of thinking through how signs operate across different sensory and conceptual domains. A sign is never just a sign—it is always part of a larger network, a shifting system of relations. My practice is guided by this relational aspect, rather than by a fixed methodology tied to a single discipline.

The process often begins with an intuition or a structural problem unrelated to a specific medium. A tension in meaning, a disruption in syntax, or a conceptual paradox might prompt an exploration that then takes form in asemic writing, sound art, or visual poetry. The choice of medium depends on how the idea needs to unfold: if it involves the dissolution of linguistic boundaries, asemic writing might be the most effective means; if it concerns rhythm and the temporal layering of signification, sound becomes a central element; if it engages with the spatialization of text, visual poetry provides the necessary framework.

That said, there are instances where form itself initiates the process. The materiality of a surface (such as sheets recovered from a flooded former paper mill near my home), the constraints of a particular notation system, or the interference between different sign systems can all generate unexpected structures that drive the work forward. Ultimately, my approach is one of continuous negotiation—between semiotic structures and their dissolution, between medium and concept, between intention and contingency. The work emerges in this tension, never fully resolving into a single, fully articulated interpretation.

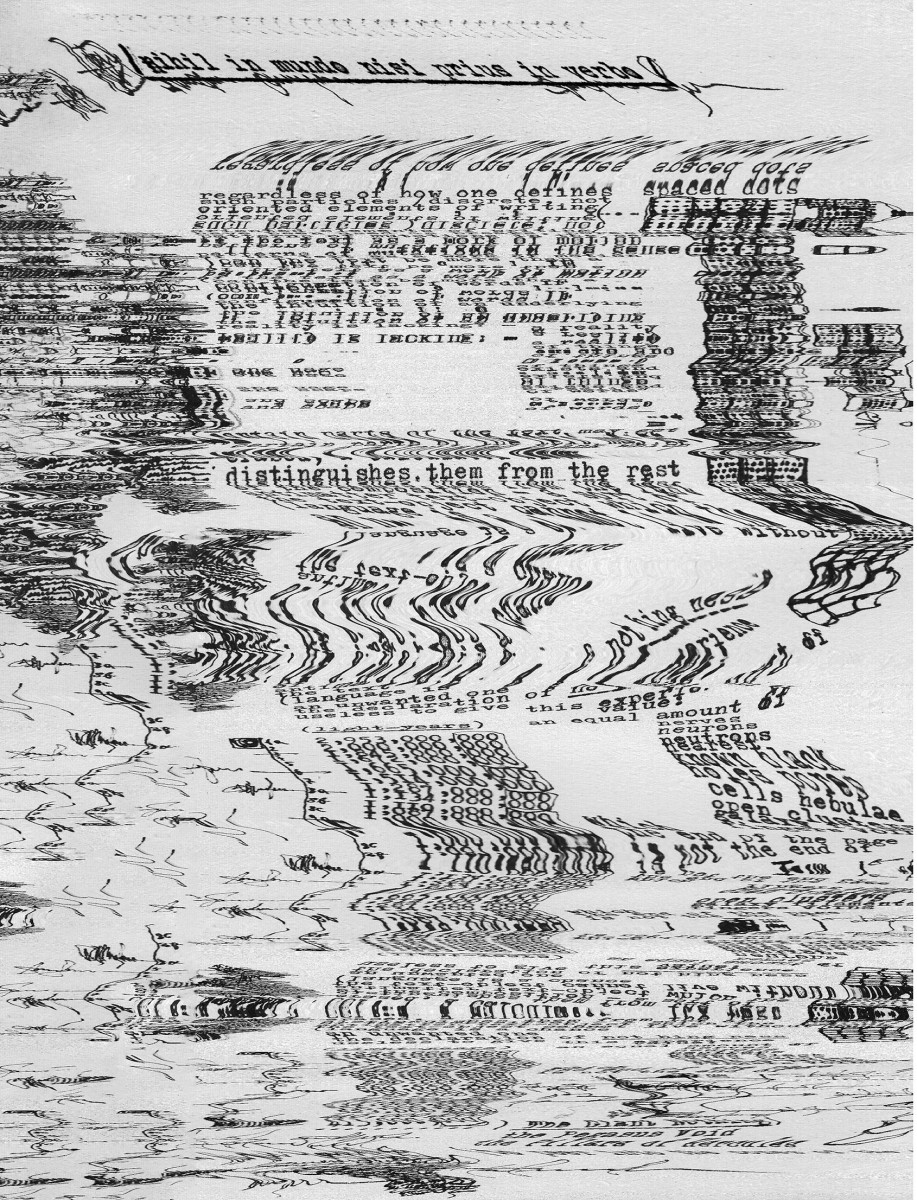

In “POLYmORPH STUdIES,” you distorted a block of text along with the notations and lines accompanying the text, so that the writing becomes partially “illegible.” Of course, it isn’t altogether “unreadable,” as if one looks close enough one can clearly make out the words, but it now primarily exists on its visual, aesthetic values. What do you make of the tension between language as meaning and language as object?

Language is never purely abstract; a material residue consistently activates it and brings it into existence. Whether inscribed on paper, encoded digitally, or spoken aloud, it tends to occupy space and time. In “POLYmORPH STUdIES,” I was interested in foregrounding this materiality—how a text, when subjected to transformation, resists or accommodates new patterns of reading.

The tension between language as meaning and language as object is central to my practice. On one hand, language functions as a system of reference, pointing beyond itself to an external reality. On the other hand, it is shaped by its own physical and formal constraints. When text is distorted, stretched, or fragmented, this duality becomes more apparent: while the signifiers still retain traces of meaning, they begin to be apprehended primarily as shapes, textures, or pure components of a visual field. Field and metric space serve as foundational concepts in my theoretical approach.

The field is the abstract space where signification resides as potential activation. It is not the visual space where signs are distributed, often unevenly, across a continuum, but a set of potential relationships triggered by the interpretive schemes of the reader or the eventual addition of other signs/signifiers with which the field interacts, adjusting itself.

In a conventional text, words are the sources of the field. Their interconnection (sentences, paragraphs, etc.) determines it as a negotiation between each word and the linguistic structures it belongs to. Each word is thus not only locally meaningful but also influences every point of the text. The more or less explicit metric (rhymes, assonances, visual disposition, etc.) formalises this underlying framework. Rhythm, for instance, even in terms of the pace of visual scanning, is its temporal component. With this in mind, the theory of gravitation and the induced warp in the geometry of space-time serve as seminal metaphors.

These concepts become even more relevant when considering asemic writing, where traditional signifieds are absent or obscured. In this context, the field exists, but its sources seem meaningless on their own. The absence of explicitly signifying signifiers does not collapse its structure. The key idea is that, even if the points/signs might not have an explicit location on a coordinate/signification grid, the relationships between them can still be defined by distance/sense. Essential structures exist independently of specific content, which is why the asemic page retains its coherence. In gravitational terms, asemic writing becomes a region in the signification space, distant from words. It shows how words inform the whole space, far beyond the conventional idea of textual space. To make a sign in that space is to allow it to react, moving in accordance with a signification field whose original sources are elsewhere or carefully hidden.

In this way, the act of reading becomes unstable in “POLYmORPH STUdIES.” One shifts between recognition and abstraction, between deciphering words and perceiving forms. This instability mirrors broader processes of signification, where meaning is contingent upon the conditions of its presentation and reception. The writing is not rendered illegible but rather subjected to a process of transformation that exposes its dual nature. The letters remain, yet their function is unsettled. This is not an erasure of language but an amplification of its multiple dimensions, where text is at once a site of meaning and a material object shaped by its own visual and spatial properties.

POLYmORPH STUdIES: pigment liner, Olivetti Studio 46, digital on 148×210 mm semi-rough sheet, 2023.

In “W.12 [ ] AIR (on the loose string, solo),” a homage to John Cage, you composed a musical score that you described as “non-playable music.” I’d love to know more about how you conceived this piece, and how you approach soundlessness and wordlessness in your projects.The piece “W.12 [ ] AIR (on the loose string, solo)” was conceived as a paradox: a musical score that exists in the absence of its own performance, a notation that gestures toward sound without ever materializing it. It is “non-playable music” not because it cannot be played, but because its execution is irrelevant, perhaps even superfluous. The notation, like a silent script, invites the performer into an interpretive space where sound becomes a possibility rather than an imperative.

John Cage famously expanded the definition of music by embracing silence, chance, and the unintentional. Here, I extend this exploration by composing a piece that does not demand to be heard. Instead, it suspends itself in the liminal zone between intention and execution, between the idea of a sound and its actualization. The score, in a sense, functions like asemic writing; it offers an invitation to read without prescribing a fixed meaning, an architecture of potentiality rather than a demand for articulation.

In this practice, soundlessness and wordlessness are not negations but openings. A blank space is not an absence but a charged field of possibilities, much like a rest in music that defines the structure as much as the notes themselves. To work with the inaudible and the unreadable is to acknowledge that meaning, like music, does not reside in what is given, but in the act of perceiving.

In the end, non-playable may simply mean that the piece plays itself—just like silence does, when given the chance.

W.12 [ ] AIR (on the loose string, solo), pigment liner on 130×185 mm Olivetti semi-rough sheet 2020.