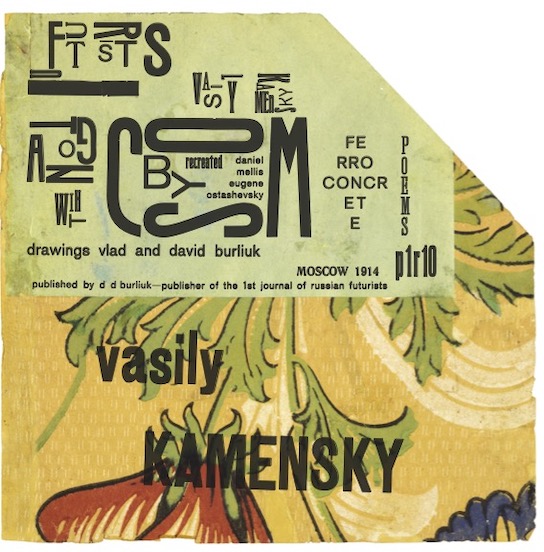

In this second installment, Sears poses questions to Ostashevsky, who recently also co-curated a pop-up exhibit on Vasily Kamensky and futurist books at the Berlin State Library.

I’d like to ask about your 2022 publication (with Daniel Mellis) of Tango with Cows by Vasily Kamensky. This was a tremendous undertaking that includes translation, commentary, and a facsimile edition of the groundbreaking 1914 book. But to begin I’m going to come right back at you with a question about the title: What is the meaning of Tango with Cows? And what was the significance of this particular book?

The fall of 1913 through the winter of 1914 was the time of global tangomania. The tango first came to Paris from, naturally, Buenos Aires. It spent a couple of years in Paris, germinating and gentrifying. Then it exploded all over the world: from California to Shanghai. Tango was not just a dance and a kind of popular music but also a phenomenon of mass consumption, a way of acting, an emancipation for the young, especially women.

Elsa Krüger, a pioneer of the tango in Moscow, dancing with her partner Wally.

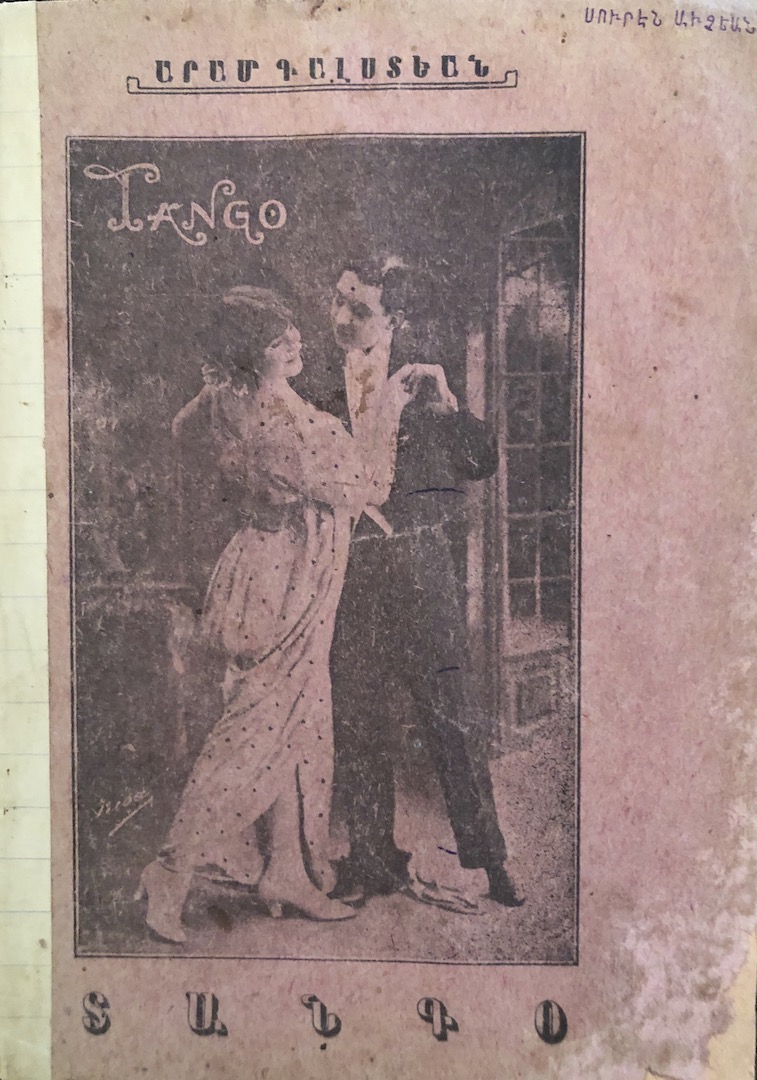

It was the twenties before the twenties. All the fashionable people dressed in tango colors, mainly orange but also other vivid tropical hues. Newspapers carried ads for tango dress shirts and tango lingerie. There were tango perfumes and tango chocolates. Young ladies wore jewelry discreetly signifying their willingness to dance the tango. And, of course, there were tango shoes. I found a chapbook of amateur Armenian poetry by one Aram Galstyan, resident of what is now Tbilisi, Georgia, in which the poet complains about the shopping frenzy—families fall apart, he exclaims, because the women are buying tango products!

Aram Galstyan. Tango. Tiflis, 1913 or 1914.

If you read entertainment magazines of, say, February 1914, it’s tango, tango, tango . . . and also futurism.Futurism was the other fad of the season—or so in Russia, which was a couple of years behind Italy. In both countries the movement was concerned with publicity, and savvy about it. The futurists baited audiences but they also responded to them in significant ways. We often think of the radical formal discoveries of the avant-garde as solutions to high art, aesthetic problems. In fact, the discoveries were motivated at least as much by the desire to shock and thereby entertain middle-class newspaper readers. Journalists joked that futurist paintings were so crazy that you never could tell if they were right side up. But young Viktor Shklovsky, in his defense of futurist poetry, cited turning a painting upside down as a way of transferring attention from the what to the how—taking it away from content to focus on formal concerns. Among Moscow theater magazines which gave futurism abundant coverage, Theater in caricatures had a one-hand-washes-the-other collaboration with the group of painters led by Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova. It reproduced futurist paintings over taunting captions (“The painting is called Bather on the Beach. Unfortunately, this magazine does not know which part of the painting is the bather and which part is the beach”). By making fun of the work, Theater in caricatures publicized it to large numbers of average readers. It also ran jeering reviews of futurist books, some of which appear to have been hoaxes, and published futurist “poems” that one hopes were self-parodies. It featured Larionov’s ideas for futurist theater and futurist fashion—ideas whose main purpose was to generate publicity by inspiring outrage. Finally, it reported on the Russian futurist practice of face and body painting, invented by the Larionov group to promote Goncharova’s one-woman retrospective in Moscow in the fall of 1913. And this is just one magazine.

Natalia Goncharova with futurist face paint and Mikhail Larionov with futurist hair for men, Theater in caricatures, September 1913.

Kamensky’s Tango with Cows was born at the intersection of the tango craze and the futurism craze.

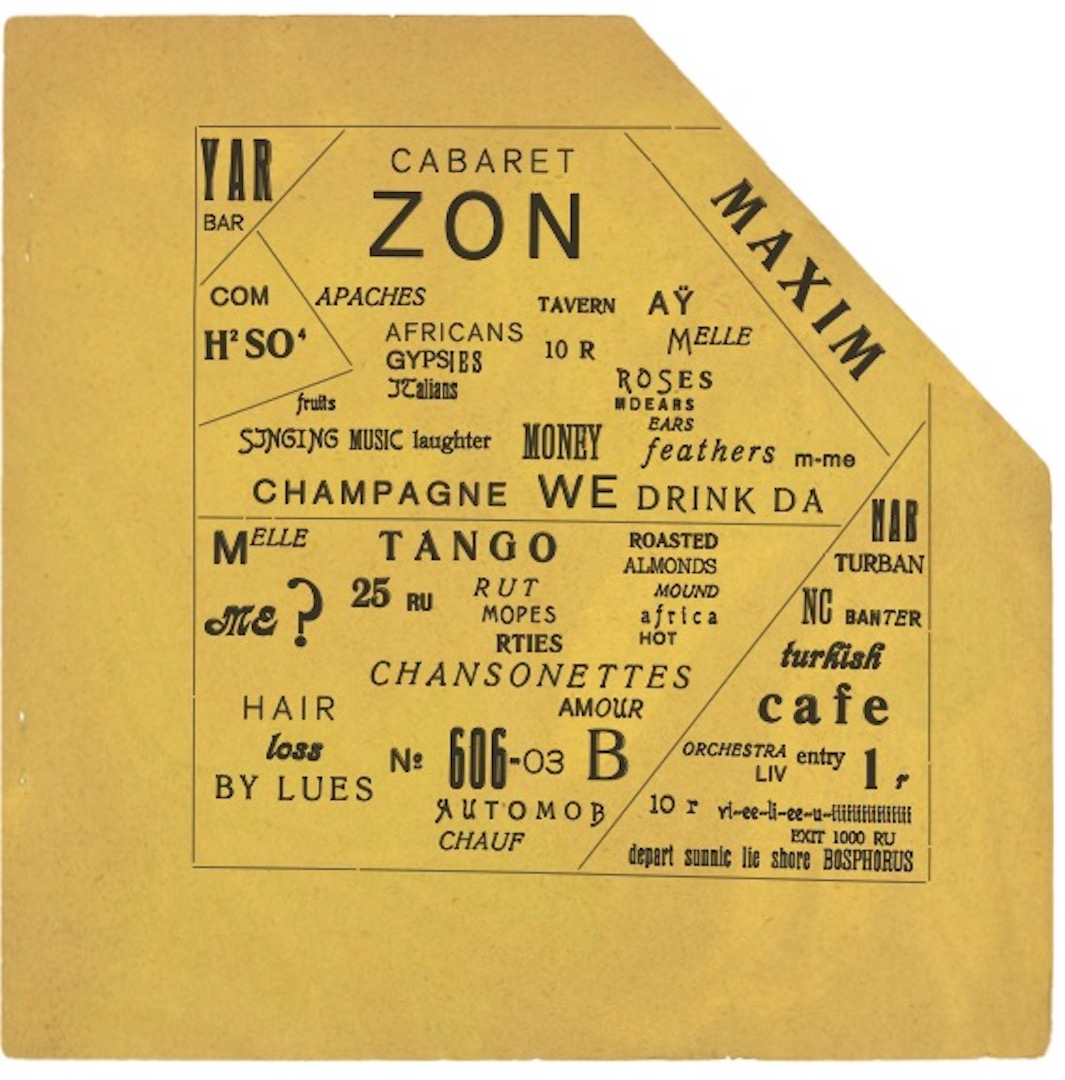

Page from Vasily Kamensky’s Tango with Cows: Facsimile, Translation, Commentary. Visual translation by Eugene Ostashevsky with Daniel Mellis. Chicago: Editions 42, 2022.

The book is printed in futurist innovative typography—the Russian amplification of Marinetti’s proposal—on the reverse side of wallpaper, in an allusion to previous futurist books edited by Kamensky, which were set on wallpaper as well. The wallpaper also suggested the collages of synthetic cubism, a hit of the 1914 exhibition season. In fact, Russian futurism was not opposed to cubism, as were the Milan futurists, but, on the contrary, fused with it, as did the “Paris futurists” Severini and Soffici. One descriptor for the Russian group that included Kamensky, Mayakovsky, Burliuk, Kruchenykh, and Khlebnikov, was “the cubofuturists.” The poems in Tango with Cows had Italian futurist grammar, being mostly composed of nouns, yet they also featured cubist punning word fragmentation. The layout of the final six poems, framed and broken up into sections by black lines, evoked cubist paintings. But the colors of the book—orange with black on the printed side, and with tropical greens, reds, and blues on the back side—were, in 1914, associated with tango products. The yellow-orange of the book, in fact, was called “tango” by that season’s marketers. Kamensky, who mentions the dance several times, sets the poems in prime Moscow hotspots: the restaurants, dance halls and even a skating rink that were the centers of the tango craze. (By the way, two of these establishments were owned by an African-American entrepreneur.) So Tango with Cows positioned itself as a tango product. As for the cows in the title, these are the newspaper readers who love to hate the futurists—the stolid bourgeois men who, in the film comedies of the time (like Charlie Chaplin’s Tango Tangles), start dancing the tango and then can’t stop.Kamensky’s and Soffici’s books were published within a year of each other, so these are really simultaneous (excuse the pun) futurist movements. One of Soffici’s poems (“Atelier,” first published in April 1915) even refers to a trip Marinetti took to Russia: “Here’s the Russian coachman with the golden top hat / Just arrived from Kiev in Marinetti’s pocket.” What was the relationship between the two movements? How were they connected, or not?

The Italian futurists received broad press coverage even in Russia. Their manifestos would be reported on and quickly translated for the general press, also under the sensationalist “those crazy artists” frame. And Russian futurist groups were carefully keeping tabs on what the Italians were doing. They reacted to Italian ideas, but in their own, quite original way, which responded to domestic concerns. The Russians were the radicals, always willing to drive an idea as far as it would go. The difference is most visible in contrasting attitudes towards poetic language. The Italians were breaking up syntax but the Russians were breaking up the lexeme, shattering the word into fragments. If Italian lexical innovation generally consisted of onomatopoeias and supported recitation needs, the Russians charged headfirst into verbal abstraction and semantic obstruction. The Russians were far more concerned with phonetic materiality, also. Tango with Cows shows the Italian penchant for lists of nouns, but its lists are held together by sound patterns, puns, rhymes, and word cuts, in a manner quite unlike Italian parole in libertà.

Marinetti lectured in Moscow and Saint Petersburg at the end of January and early half of February 1914 by the Russian Julian calendar, two weeks behind the Gregorian calendar of Western Europe. The press idolized him because he was a wealthy Western celebrity and used his futurism to clobber his Russians colleagues, whom the journalists dismissed as plagiarists and impostors. Naturally, Russian artists denied Marinetti’s influence and denounced him as a conservative. Mayakovsky and Burliuk were supposed to debate Marinetti at the Society for Free Aesthetics in Moscow on February 13, 1914, but their French wasn’t good enough, and the moderator refused to let them speak Russian.

Mayakovsky and Burliuk preparing to debate Marinetti with the critic Andrei Shemshurin, Moscow, February 1914.

By contrast, Ilia Zdanevich, the spokesman of the Larionov-Goncharova group, whose father was a French teacher, was able to communicate with Marinetti. Still, most of the communication took place offstage, in the night, when they all went drinking together. Marinetti later bragged that he downed four bottles of champagne in a single night at the Stray Dog in Saint Petersburg, just to show the Russians that Italians are better than them even in drinking.How much did Marinetti get from the contact? It’s not clear. The influence was mostly one-way, because he didn’t have the language. But it seems he was presented with some futurist books. Daniel Mellis, my partner in the Tango project, thinks that Kamensky printed The Naked among the Clad, which has most of the poems of the Tango in it, to offer a gift copy to Marinetti. Perhaps that gave the Milanese poet a shove in the direction of tavole parolibere (freeword tables or panels) where the page serves as the space of the poem, as it does in Tango but not so much in early parole in libertà (“words in freedom,” the poetic language of Italian futurism, which used simple typographic means to make up for its syntactic primitivism). But this is just speculation. No copy of The Naked among the Clad has surfaced in Marinetti’s library, to the best of my knowledge. And the Italian futurists were already moving in the direction of tavole parolibere, anyway. Another cubofuturist, Benedict Livshits, claims in his memoirs that he lectured Marinetti on zaum’, Russian futurist sound poetry, and, indeed, Marinetti’s next manifesto, “Geometrical and Mechanical Splendor and the Numerical Sensibility,” published right after his return from Russia, does feature a category of abstract onomatopoeia.

Kamensky invented the term “ferroconcrete” to describe his own form of avant-garde typographic visual poetry. How does a “ferroconcrete” poem differ from the other typographically innovative poems of futurism and also from the “concrete poems” of the 1950s and 60s?

Kamensky coined the term “ferroconcrete poetry” to refer to the genre of typographic poem-picture which he invented in January of 1914, and which appears in the second section of Tango with Cows. The poem-picture, with its columns of nouns set in sections separated by black lines, visually suggests reinforced-concrete construction, the most state-of-art building technique in the 1910s. But Kamensky immediately extended the term to cover all of his typographic experiments, and then to everything he did, including art installations. While on tour in March 1914, he was publicly contrasting the “ferroconcrete poetry” of the futurists with the “chocolate-and-candy poetry” of the nineteenth century.

The lexical closeness between the term “ferroconcrete” and the 1950s term “concrete poetry,” such as that of the Noigandres school in Brazil, has been remarked upon. But that lexical closeness was born in the crib of translation, since the Russian for “ferroconcrete,” “zhelezobetonnyi,” i.e., made of reinforced concrete, is based on the word beton, which is not a cognate of concrete, but its translation equivalent. Nonetheless, the unintended pun is felicitous, because both terms suggest a parallel between one and the same poetic technique and one and the same building technique. Although the word “concrete” in poesia concreta does function as the antonym of “abstract” or “vague,” it also has an architectural dimension. To call this kind of poetry “concrete” in 1950s Brazil implicitly compares the linguistic modularity of the signature technique of the new style, where letters are moved around to create new words, to the modularity of prefabricated construction—those concrete apartment and office buildings going up in Sao Paolo. Linguistic modularity is also a feature of the poetics of Tango with Cows, in which the word is conceived as a string of letters that may be moved around to create other words. So do I regard “ferroconcrete poems” as ancestors of “concrete poems”? Yes.

As far as other futurist typographic experiments go, simultaneity in Kamensky mainly consists in viewing the poem as a constellation of words without a single obligatory reading order on the space of a single page. This type of simultaneity is not characteristic of early parole in libertà, where the reading order tends to be linear and conventional. Nonetheless, in your book a similar simultaneity appears in “Station Cafeteria” and “Typography.” Other people are also beginning to do it in 1914, making way towards the wartime tavole parolibere finally published in 1919 in the Les mots en liberté futuristes. And the same type of simultaneity appears in the language of Dada photomontages.

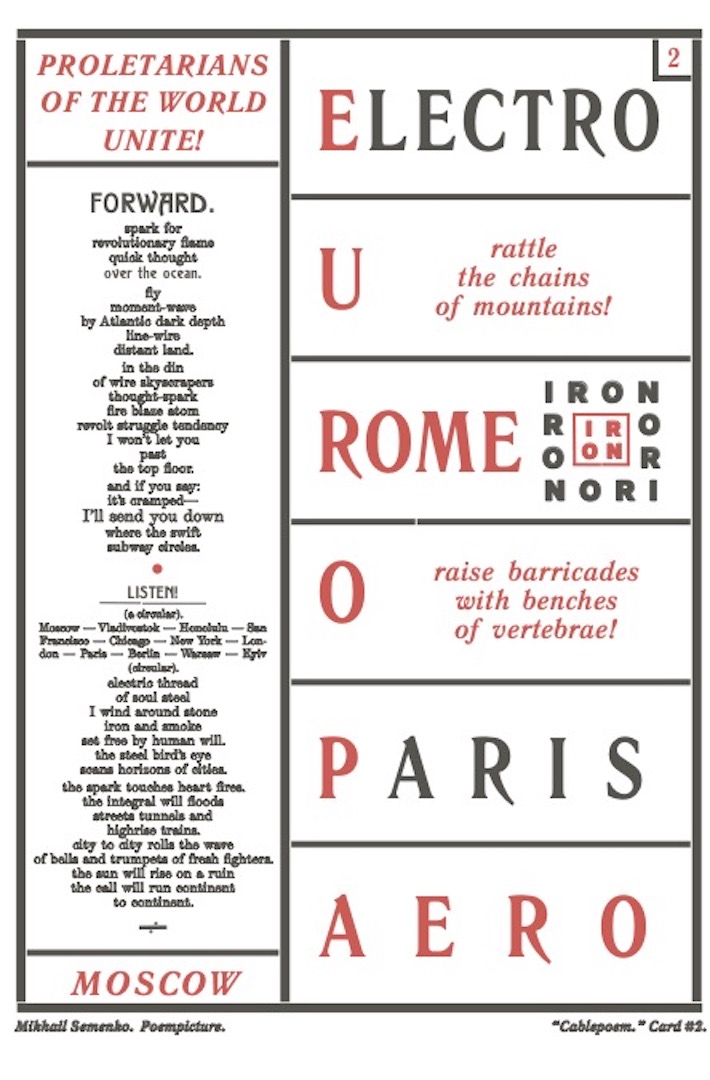

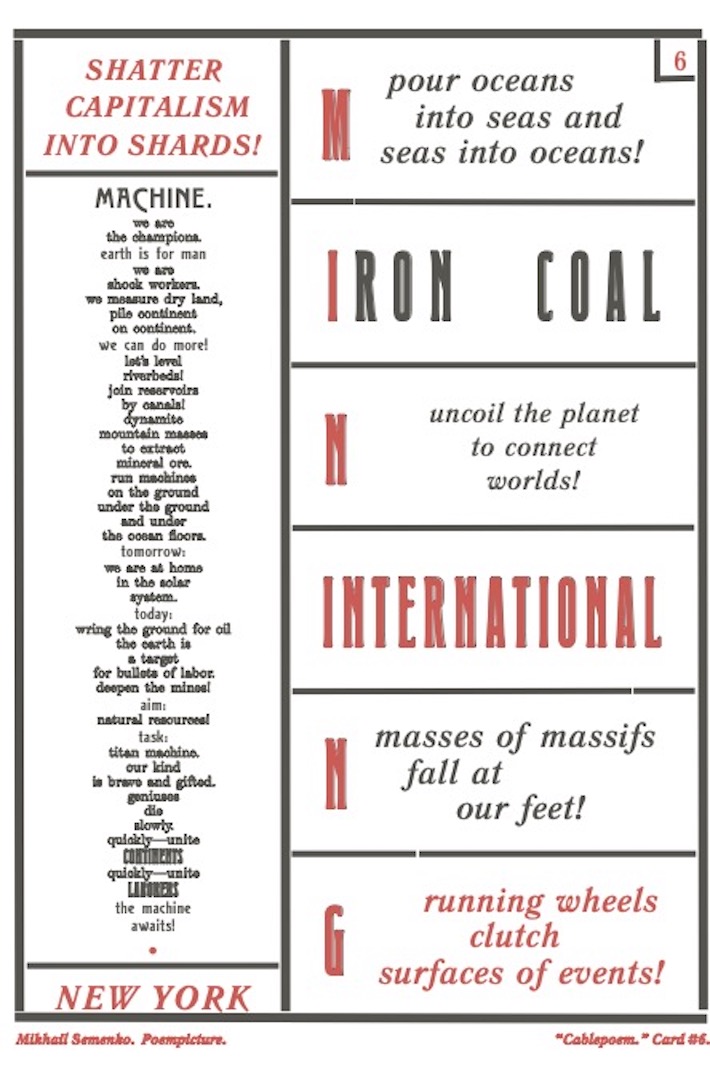

But I want to finish by indicating lesser-known typographic poems by another, lesser-known futurist group—the Ukrainian panfuturists of the early 1920s, led by the poet Mykhail Semenko, who originally founded Ukrainian futurism in the winter of 1914, but World War I put that project on pause. When Ukrainian futurism reconstituted itself in the early Soviet period, it called itself “panfuturism,” to emphasize its openness to all the new techniques of the international avant-garde. The panfuturists, who presented themselves as communist artists, argued that bourgeois aesthetics must be replaced by rational, scientific, process-based, and technologically savvy new art, intended for everyday life rather than museums and libraries.

In 1922, the group published a collection called Semafor u maibutnie, meaning something like “A Signaling System into the Future” or perhaps “for those Headed into the Future.” The collection carried a series of Semenko pieces called “Cablepoems,” or Telegraph-poems, of a poem-poster genre he called poezomaliarstvo, “poem-painting.” Content-wise, they constituted early and even vatic attempts at the art of Soviet industrialization, suggesting that industrialized Soviet Ukraine will assume its rightful place among other focal points of modernity, such as New York and Paris, and soon everybody will fly to Mars and defeat the bourgeoisie. I translated a couple with Ostap Kin, and Daniel Mellis did a computer sketch of the layout.

Mykhail Semenko, Cablepoem 2, translated by Eugene Ostashevsky and Ostap Kin.

Mykhail Semenko, Cablepoem 6, translated by Eugene Ostashevsky and Ostap Kin.