In this first installment, Ostashevsky poses questions to Sears, and in the second installment, which will appear in the Fall issue of Asymptote, the conversation continues and develops, as Sears turns the focus to Ostashevsky work.

Two years ago, World Poetry Books released your translation of Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms, a book of poetry by the Italian futurist Ardengo Soffici, published during World War I under the strange title of BÏF§ZF+18. Who was this Soffici that he should title his books in this preposterous manner?

Ardengo Soffici (1979–1964) was quite an eccentric character, but he was also a central driver of the early twentieth-century Italian avant-garde. As one of his closest friends put it, “Attempting to interpret Soffici is laughable; to explain him, impossible; to define him, unnecessary; and to defend him, ridiculous. You have to take him or leave him, just as he is.”

Soffici attended art school in Florence and then around 1900 fled the dusty torpor of the local art scene to spend his formative years in Paris, where he made a name for himself as a painter and art critic in the circles of Picasso and Cézanne, and later the poet Apollinaire. Back in Florence, he organized exhibits for all his artist friends (including Degas, Matisse, Rousseau, and Braque), introducing cubist and impressionist painting to Italy for the first time. He cofounded several journals that helped develop an avant-garde milieu in Florence and for a time promoted his own brand of Florentine futurism, often in tension with the famed futurists from Milan (led by F.T. Marinetti), provoking well-publicized barroom brawls. Historians estimate that Soffici’s most famous magazine, Lacerba, had a circulation in excess of twenty thousand readers at its height.

Soffici was thus an established artist and cultural figure by the time Lacerba began to publish his poetic experiments in cubist writing, parole in libertà (words-in-freedom), and expressive typography, which would eventually culminate in the collection I translated, Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms. Early in the book, Soffici’s poetic narrator forthrightly declares the poet’s position: “A great joy it is to be this electric dynamo in the midst of history / Taller than the Eiffel Tower jet of flame.” In another poem he writes, “Every painting is a window on the frenzy of life / I am a thrower-open of windows / And senses / Every color / Sings like a bird.” These self-characterizations—as a fiery energy source glowing and buzzing at one of Europe’s busiest intersections and blowing the windows of perception wide open—capture the essence of Soffici’s significance: he was an alchemist at the intersection of the literary and visual arts.

His book title brings together the names of the book’s two sections. The first section, whose poems are largely free verse, is called “Simultaneities.” Simultaneity was a fashionable and polysemic word in the 1910s, meaning different things in different areas of culture. What does he mean by his unusual book title? What are Simultaneities?

As it happens, Soffici helpfully wrote a manifesto defining all the terms he uses. He explains simultaneità in poetry like this: the artist is “the mobile center of the living universe” and the poem is “a flow, a fabric of sensations diffused concentrically around the expressive point of genius—the creator.” Rather than the unfolding of a particular theme or the expression of a single sensation, the poem is a “simultaneous amalgam” of everything the poetic self experiences: the sights he sees as he walks the streets, the sounds and smells, the memories and emotions triggered—all swirling together on the page.

The “Simultaneities” section of the book comprises twelve free-verse and prose poems laid out in standard typography but with jumbled syntax and almost no punctuation, leaving the reader without the usual navigational tools. The poetics mirror the blur of cityscapes and billboard advertisements as seen from a speeding car or train, or the sensory overload of nonstop advertising—all novel experiences at the time.

Among other things, the “Simultaneities” were Soffici’s attempt to cope with the sudden radical changes that society faced in the throes of modernization. New inventions and discoveries were completely transforming the experience of daily life, from its infrastructure to its rhythms. Speeding trains and airplanes confounded notions of distance and space; the telephone and the telegraph made human communication instantaneous. Einstein’s theory of special relativity was upending physics, introducing the preposterous notion of a space-time continuum, like another Copernican Revolution. Technology was galloping ahead and dragging everyone along at high speed while the inherited culture languished in the twilight. Soffici's remedy was poetry intended to overwhelm the reader's defenses.

As you say, the term simultaneity in poetry had more than one meaning during this decade. For Soffici, its meaning was primarily psychological: representing the inner life in his poems alongside outer physical reality, simultaneously and without distinction. Soffici writes, “Generally a work of art has been based on a motif (pictorial, literary), which was a portion of reality cut out in space or time and framed in itself. The simultaneous work of art will instead consist of a flow of sensations . . . without a framework.”

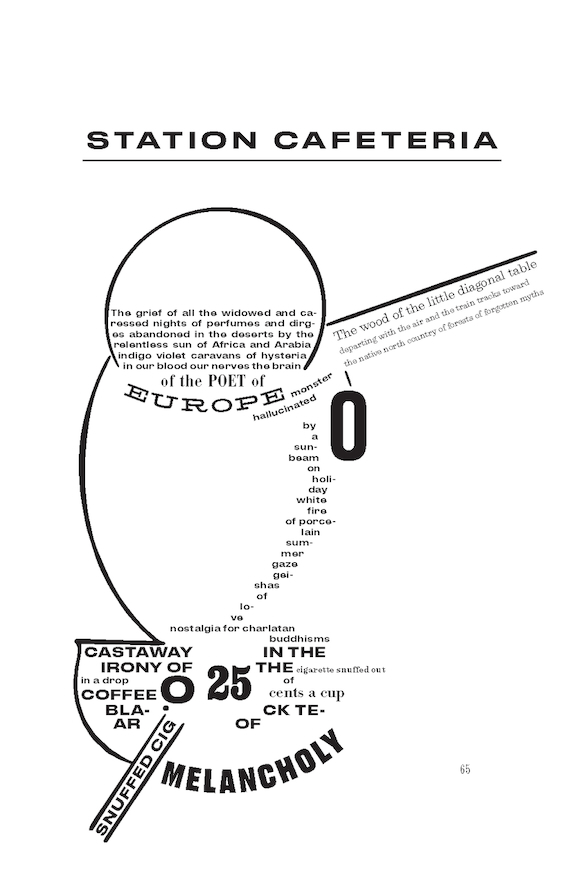

The second section of his book, “Lyric Chemisms,” consists mainly of what Italian futurists called parole in libertà, or words in freedom: prose with reduced syntax but flashy and changing. Or rather, that’s what parole in libertà looked like in its early phase, in winter 1913-1914. However, a couple of pieces in that section are more complex. One, “Station Cafeteria,” is a typographic figure poem, like Apollinaire’s Calligrammes. Another, “Typography,” looks forward to the tavole parolibere, the anarchic compositions in type that the Italian futurists developed mainly during World War I. Why “Lyric Chemisms”? What does that term mean?

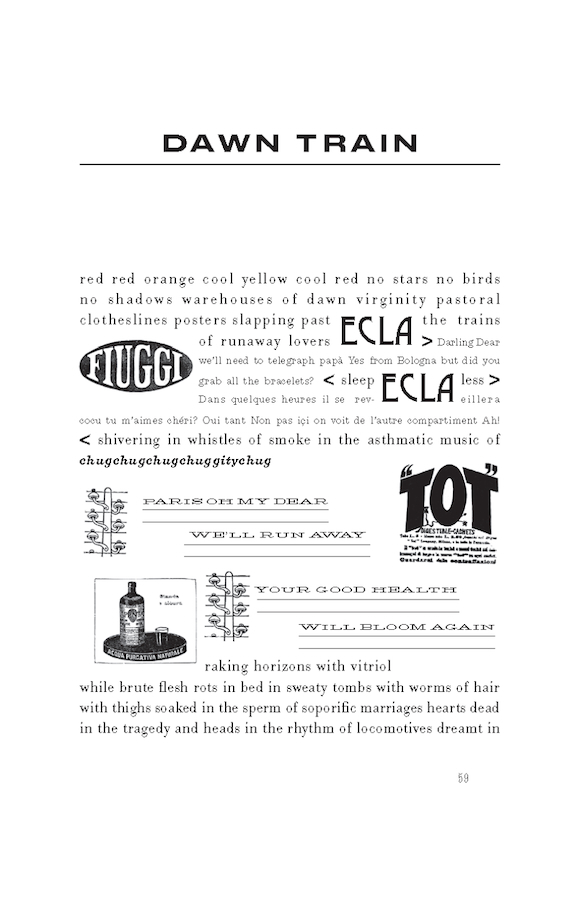

Soffici’s “Lyric Chemisms” were said by a contemporary critic to be “as haphazard as life itself,” with their expressive typography and absurdly inclusive assemblages—once again embodying the overwhelm of modern existence. The ten poems of this section teem with chaotic catalogs of typefaces, brand names, songs, and snippets of dialogue, all of which Soffici felt should be elements of a poem’s meaning—allowing words and noise from the background of life to emerge in the midst of poems.

So, to your question: why “lyric chemisms”? Soffici was fascinated by chemical processes, but he was also attached to the more occult concept of alchemy. When he coined his chimismi lirici, he was undoubtedly riffing on Rimbaud’s alchimie du verbe (alchemy of the word), and he transformed the mystical into something more modern, using the kind of scientific language that futurists liked to sprinkle in their poems. (“Chemism” had a precise meaning in science and philosophy in Soffici’s day—I won’t bore you with that here—but it could be used more generally to mean a “chemical action.”) The central notion was the same: disparate elements melding or transmuting through some potentially violent process. In the same manifesto, Soffici describes a lyric chemism as an “amalgam” (the result of a chemical process) of the real and the artificial in the poet’s “crucible” where the “unexpected rapprochement” of living elements (words, shapes, colors, sounds) will create “an emotional effervescence of great vibratory power.” He advises the poet to establish “a simultaneous framework of lyrical figures . . . whose relationship, or contrast, causes a fantastic radiation”; as the painter does in his distribution of paint, the poet should “organize a verbal evocative whole capable of propagating and acting, as a fluid or an explosive charge.”

And what on earth is BÏF§ZF+18, the original Italian title? Soffici’s lover, the Ukrainian painter Alexandra Exter, seems to allude to it, or to some of it, in her still life of 1913 at the Thyssen-Bornemysza in Madrid.

Good question! The late, great critic Marjorie Perloff (whom we lost just this spring) quipped that BÏF§ZF+18 would make a good ATM password. (I highly recommend reading her wonderfully entertaining foreword to this translation!) Soffici explained, years after the book came out, that the intentionally unpronounceable title was suggested by the “bizarre combinations of typographical letters and signs . . . used to construct the page for print”; to him it seemed expressive of “the fantastic singularity of the text.” His typesetters—looking for an easier way to refer to this bizarre book day in and day out—began to pronounce the title “Bizzeffe,” an expression that means “piles of” or “abundant” (apparently an Italian colloquialism from Algerian Arabic), and the nickname is still used today. In this translation we ultimately decided to title the book simply Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms. I argued to include some version of the original nonsense title, but the publisher rightly pointed out that “BÏF§ZF+18” would stump all the digital databases where book titles appear and that the nickname “Bizzeffe” would be read as mere gibberish. Fair enough. I was content to have BÏF§ZF+18 appear on the cover, which is a gorgeous re-creation of Soffici’s original cover collage.

Most of the poems in Simultaneities are paratactic free verse, whose effect is due to accumulation rather than precision. Others, like his famous “Station Cafeteria,” are typographic, visual constructions, which would lose their effect if they were printed any other way. Is there anything that unites these two poetics? Are they futurist, cubist, or in-between?

It’s true, the two sections of poems look very different from one another, but they actually have a lot in common. For me what unites the Simultaneities and the Lyric Chemisms is Soffici’s visual and spatial imagination, the result of “the everywhere-ness and always-ness of the sensing, creative body”—especially when that creative body was trained first and foremost as a painter. Because Soffici wrote copiously about his own work, we can also read his own words: He writes that the poet observes the facts and things of the world as they collide and interpenetrate and chaotically bounce around, and this activity stimulates the imagination which, like a crucible or an alembic, then anneals, distills, and transforms them. He describes the resulting Simultaneities as “a flow, a fabric of sensations” whereas a Lyric Chemism is “capable of propagating and acting, as a fluid or an explosive charge.” I’m leery about assigning absolute labels to Soffici’s poems (beyond these vague characterizations) because even individually they seem too squirrelly to fit neatly into any one camp. Maybe I’m skirting the question here with Soffici’s words, but ultimately I think his poetics were eccentrically his own.

Reading the poems closely, it’s also clear that these two modes are not as distinct as they look, nor terribly consistent within their categories. The Simultaneities are less conventional free verse than they appear; they strongly resist linearity and are full of color and movement, not only due to the parataxis you mention (that is, the lack of connective tissue between fragmentary phrases), but also the melding of interiority (memories, associations) and empirical reality, and the quick cuts and synesthesia among sensory inputs (smell, taste, sight, hearing). Here’s a brief example:

Countries hours—

There are voices that follow you everywhere like the moon or a dog

But also the whistle of a smokestack

That mixes up the colors of the morning

And of dreams

No, you won’t forget the fragrance of certain nights drowned in armpits of topaz

These cold narcissus that I keep on the table by the inkwell

Were painted on the walls of Room 19 of the Hôtel des Anglais in Rouen

A train was rambling along the quay late at night

Beneath our window

Beheading the reflections of multi-colored lanterns

Among casks of Sicilian wine

And the Seine was a garden of blazing flags

—from “Rainbow”

Voices can follow you, a whistle can mix colors, a train can behead reflections, and a river is a garden of flags.

I’d argue that the Simultaneities create an experience for the reader that’s just as “visually” striking as the Chemisms, though not presented as such on the page. They’re full of painterly images expressed in words (requiring the reader’s imagination) rather than in graphics and typography. Similarly, many of the Chemisms appear futurist on the surface (with their expressive typography and other elements), but unlike similar poetry of the era (like your Vasily Kamensky, Eugene), they're quite legible and have a clear predetermined reading order. Not surprisingly, Soffici himself, despite authoring many treatises delineating his aesthetic ideals in detail, never chose to stay in one lane. From the start of the movement, he was a rabid anti-futurist—that is, until he became the loudest public champion of futurism in Tuscany; he then returned to utter antagonism, all in the course of two years.

Coming to the project of poetic regeneration as a painter and critic steeped in contemporary French aesthetics—both in visual art and in the most innovative poetry, like Apollinaire’s—helped him chart (or invent) his own course between Italian futurism and the various strains of the French vanguard, influenced by all of them but wholly embracing none. As an experienced cubist painter and collagist who worked closely with Cezanne, Picasso, and Braque, Soffici translated to his poetry the propensity to collapse time and to view life simultaneously from different angles based on the concreteness of objects. He saw cubist techniques as the means to break the boundaries of ordinary vision and make it “continue in infinite vibrations in the imagination of the reader.” (One critic calls Soffici “temperamentally cubist.”) But he also attributed some of his ideas to the Impressionists, like the transformation of commonplace objects and experiences in art—what he calls the “panpoeticity” of things.

In addition to the impact of visual art on his work, there’s his close relationship with Guillaume Apollinaire. During Soffici’s first period of antagonism toward futurism (1909–1913), he maintained a reciprocal exchange of ideas and techniques with Apollinaire. Throughout 1912 and early 1913, Soffici was writing his Simultaneities in parallel with Apollinaire’s composition of Alcools, a masterpiece of poetic simultaneity, which heavily influenced Soffici with its melancholic tone and embrace of nostalgia.

By 1913, Soffici and his coeditors had realized that to build their own avant-garde movement they needed to ally with the futurists—just at the moment when Apollinaire was himself warming up to the precepts of futurism. Not coincidentally, Apollinaire published a manifesto entitled “The futurist Anti-Tradition” in the same edition of the magazine Lacerba where Soffici published his first Chemism, “Still Life.”

Ardengo Soffici, “Still Life” (1913/2022), Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms, translated by Olivia E. Sears, World Poetry Books (2022), 49.

Soffici’s first Chemism does not scream futurist, given the title (“Still Life” doesn’t promise something dynamic or radically new) and the content (a detailed description of Soffici’s own cubist painting, “Decomposition of the Planes of a Lamp,” 1912–1913):

Ardengo Soffici, Scomposizione dei piani di una lampada (Decomposition of the Planes of a Lamp), oil on panel, 1912–1913, Estorick Collection, London, UK.

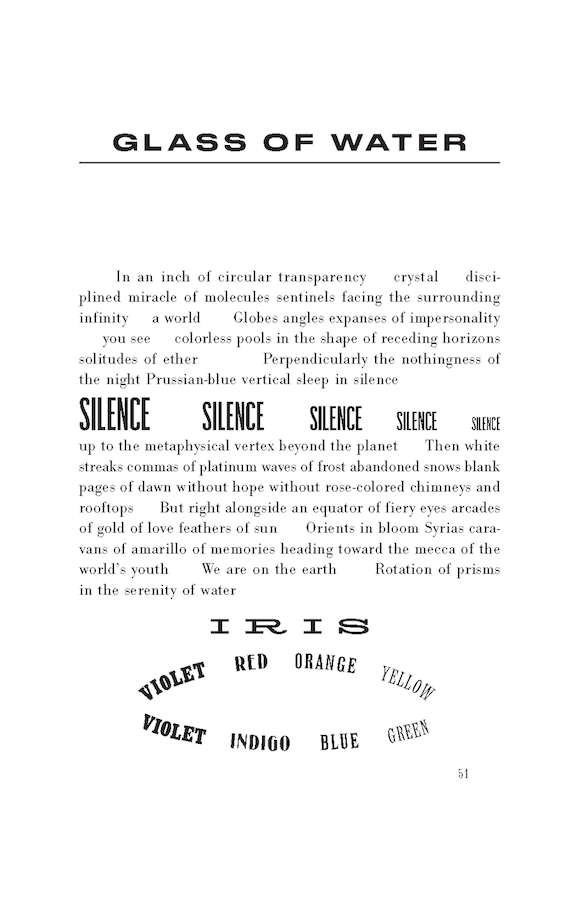

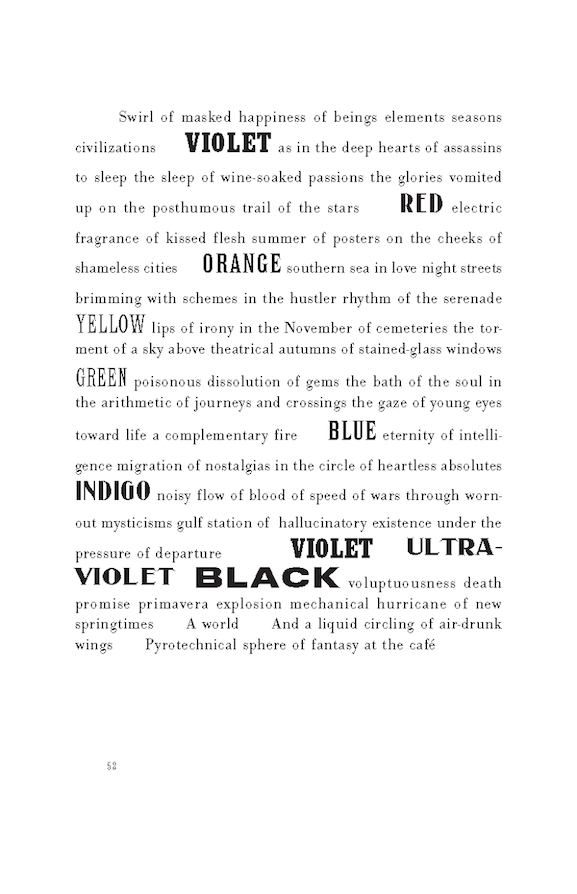

Both were unexpected but not revolutionary. But this was Soffici’s first small gesture toward the movement.In January 1914, Soffici argued in Lacerba that the “radically new subject matter” of the modern era demanded a radically new mode of expression. Yet in the following issue he published his first parole in libertà (his radically new words-in-freedom) with a subject matter that was not terribly radical, new, or modern: “Glass of Water.” As the critic Willard Bohn has observed, the poem appears vaguely futurist at first glance (a variety of typefaces and font sizes, no punctuation, a smattering of urban and artificial references) but many of the features futurism is best known for (like its dynamism and polemical tone) are missing and, like “Still Life,” the language is impressionistic and hallucinatory, more cubist than futurist. The main concrete feature is the eye below the word “iris,” here referring to the spectrum of visible light as well as the colors of the rainbow; in Italian, “iride” can mean the iris of the eye or a rainbow (from the ancient Greek word for rainbow and the mythological goddess). Other critics have suggested that this was Soffici's first calligram and may have actually influenced Apollinaire’s renowned “Il pleut,” which was published later the same year (July–August 1914).

Ardengo Soffici, “Glass of Water” (1914/2022), Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms, translated by Olivia E. Sears, World Poetry Books (2022), 51–52.

Ardengo Soffici, “Station Cafeteria” (1914/2022), Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms, translated by Olivia E. Sears, World Poetry Books (2022), 65.

Ardengo Soffici, “Dawn Train” (1914/2022), Simultaneities and Lyric Chemisms, translated by Olivia E. Sears, World Poetry Books (2022), 59–60.

By December 1914, Soffici had published most of the Chemisms he would compose, and in February 1915 he publicly broke with the futurists. He’d already returned to writing the Simultaneities, which he’d suspended early in 1913, and he published almost all these free-verse poems in his two magazines (La Voce and Lacerba) in the spring of 1915. These poems were much more in keeping with Apollinaire’s style, and full of features the futurists deplored.

Given Soffici’s French connections and the many cubist aspects of his work, not to mention his tendency to flout many of the precepts essential to futurism, why is Soffici usually categorized as a futurist?

Although his alliance with the futurist movement lasted for only one year, there were several things that indelibly associate Soffici’s name with the movement. His magazine Lacerba was the last magazine he edited as an avant-garde writer (before World War I caused his about-face—which is another story) and Lacerba went all-in on futurism. Soffici himself wrote a few important aesthetic treatises involving futurism during that time (although some were critical of Marinetti's stranglehold of the movement). Generally, critics cite a handful of his parole in libertà as iconic of the movement—though I’d argue it was Soffici’s long experience as a collage artist with the cubists and devotion to their techniques that made his parole in libertà most successful, not their futurist qualities. Of course, the Simultaneities also have futurist elements, like parataxis, as you mentioned—that steady piling up of brief syntactic fragments “without strings” of punctuation or conventional syntax—and Soffici heartily embraced other innovations of futurism (like repeated infinitives, urban imagery and scientific references, reclamismo or billboard slogans, and of course new typographical features).

But Soffici was seemingly incapable of conforming to externally imposed rules, especially those coming from the militant and rigid Marinetti. Soffici’s work lacked the essential futurist fury—the polemics, the violence, the radical break with the past, the machinery, the anti-humanism—and in all their color and vibrancy, Soffici’s poems were frequently imbued with melancholy and nostalgia, both moods specifically prohibited according to futurist doctrine. More than anything, though, where futurism called for the absolute abolition of the authorial I, Soffici places the observing (and often vociferously participating) subject squarely at the center of his roiling universe, what he called “the point of genius—the creator.”

Soffici sought an avant-garde movement to effect a renewal in the visual and literary arts. But he never really fit with the futurists or in the role of a follower. As his collaborator Giuseppe Prezzolini wrote at the time, the temporary alliance with the futurists was born from the hope that Soffici and his collaborators could help urge futurism—Italy’s only native avant-garde movement at the time—closer to Modernism and further from the cult of futurism’s famed founder, F.T. Marinetti. Soffici did manage to establish a distinct Florentine futurist scene, but its work was perpetually drowned out (and continues to be) by Marinetti and his raucous crew. My hope with this translation is that the culminating poetry collection of Soffici’s avant-garde career will emerge from the general clamor of the futurist era as the unique alchemical amalgam it was.