Chimal coined the term “literature of the imagination” to describe his writing style: It is loosely parallel to “weird fiction” and distinguishes his literary output from science fiction and fantasy. Chimal often employs photography and images with his writing, in hybrid formats, on and off the internet.

I first met Alberto in 2020 at the Under the Volcano literary community in Tepoztlán, México, where I had the privilege of taking his short flash fiction workshop. Chimal proved expert at drawing out the shy writers among us with his humor and gracious comments about their contributions to the lively, participatory session, and his agile mind and linguistic precision made a deep impression on me. So, when he invited me to translate Historia siniestra (Scary Story; Pamenar Press, 2023), I jumped at the chance to collaborate with him and render his concise, incisive, and poetic prose in English.

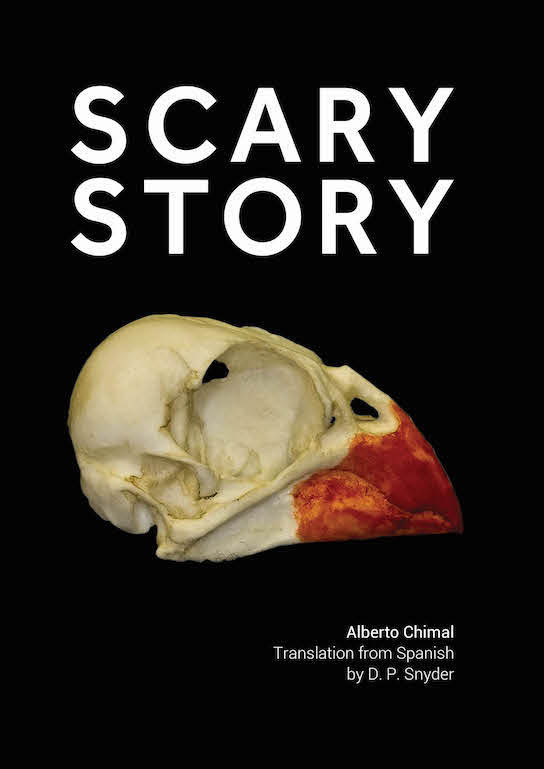

Scary Story, originally published as Historia siniestra (Cuadrivio, 2015), is composed of two narrative poems originally published on the internet, specifically on Twitter, and later adapted for the printed page. As described in Scary Story itself, Part I, “X City,” is “a hybrid text, equal parts horror story and political poem, and it takes the form of a countdown, imperceptible to everyone in the universe of the story itself.” It references and protests many things that were happening in Mexico when it was written, including the disappearance and murder of forty-three young men from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Normal School, a teacher-training college in Ayotzinapa, who were executed by drug traffickers in collusion with local politicians. Part II, “An Ordinary Day”, features Horacio Kustos, a character who appears often in Chimal’s work and who here can't enjoy an uneventful walk because everything he sees betrays a sinister undercurrent. The text, with accompanying photos taken by the author on his iPhone, was one of the projects selected in 2014 for the International #TwitterFiction Festival, dedicated to experimental narratives on Twitter.

Chimal’s outreach to the reading and writing public through his website, workshops, a YouTube channel, and a Substack he maintains with his partner, writer Raquel Castro, his creative use of social media, and his groundbreaking literary opus is well-known. Less studied, however, is the thinking behind this prolific output, in particular his innovative image–text creations, which, like most highly innovative literature, is under-examined and often misunderstood.

In a “ping-pong” interview via email, Chimal and I discussed the photographic, symbolic, and textual images in his book Historia siniestra, my translation of it into English as Scary Story, the place of the image in “literature of the imagination,” and how photography and art continue to inform his work. As is customary for us, whether we're emailing or hanging out in a café in La Condesa, the conversation took place bilingually. We appreciate being allowed to present it at Asymptote in both languages.

Below is a brief excerpt of “An Ordinary Day,” including my translation of the text and Chimal’s images, followed by our conversation. More images can be found in the slideshow above.

The Cafeteria

The man opened the trunk of the car.

I didn't understand what was inside, screaming.

Pacheco Avenue

I have more just like that and prettier, he said.

Are you sure you don't want to come down?

Nagaoka Temple

“It’s not a scam. The Leader died in 1976,

but video triumphs over death.”

He agreed.

Oddly enough, I’d like to start our chat with a quote from your 2010 collection 83 Novelas. Like “X City” and “An Ordinary Day” (the two parts of Scary Story), it was first published on the Platform-Formerly-Known-As-Twitter, hereafter referred to in this interview as Ex-Twitter. In my translation, the flash novel The Storyteller reads:

Images, not words, came out of his mouth: action figures

who fought, kissed, and spoke with panache and vigor.

“Too visual,” complained a critic.

Does this mini novel reflect your impulse and experience regarding the intersection of written language and image? Do you think critics have overlooked or misunderstood the visual aspect of your work? Finally, would you offer readers a brief definition of the genre you gave birth to, “literature of the imagination”? Oops, that's three questions.

Do you see what a good idea it is to communicate in writing, dear Dorothy? If we were talking live, I would have forgotten two of the questions by now. ;)

I hadn’t thought about that flash again in quite a while, but yes. There’s something about the intersection of image and writing that fascinates me. It must have started with the comics I read as a child, which have never stopped intriguing me as a literary form. Now, I find it in many very different works, from the novels of W. G. Sebald to the illustrated stories of Edward Gorey (and more comics), and I’ve been playing with it in my books for a long time. That said, I don’t think any critic has ever mentioned it. Several give me the impression of having the attitude of the one in the flash. And it’s also true that I write in an environment where the interplay of imagination and formal experimentation isn't typical. There's no tradition of considering those possibilities in literary fiction.

As for “literature of imagination,” I define it as the set of narrative works that use the fantastic imagination as a specific discursive mode, especially when they do not belong to a particular [established] subgenre or genre. Much of my early reading was what is called in English “genre fiction,” even before I understood what that was, and I don't want to abandon all it gave me. At the same time, however, all the genres I became familiar with when I was young were produced in English-speaking countries and under socioeconomic circumstances that have come and gone and were never applicable to the country I grew up in. They are inadequate to describe the experience of those of us who live in the global south today, even if we persist in employing them here. For me, inventing a new classification is an attempt to break out of the closed compartments of genres, and I am glad that this label has taken hold in Mexico over the last few years.

Let’s briefly talk about Sebald and his novel that transformed my idea of what fiction could be: Austerlitz (trans. Anthea Bell; Random House, 2001). For Sebald, images are integral to the generation of the work, not simply illustrations laid into the text later. You share that dynamic with him. But Sebald’s galleries are a mix of his photos, “found” objects, and artifacts given to him by others—the famous little boy in the Cavalier outfit on the cover was an actual friend of the author. By contrast, all the photos in Part II, “An Ordinary Day,” are yours. As you were shooting them, were you composing the accompanying text on the spot and uploading them to Ex-Twitter in real time? Or did you choose them later and assemble Horacio Kustos’s journey according to the images you had? All the photos are from Mexico City, right?

You make me remember the first time I saw that book by Sebald in the window of a bookstore. Reading it impacted me deeply, too. On the other hand, while the melancholy imagery has an undeniable power, it’s not one I could have used in “An Ordinary Day.” That project (like “X City,” in its own way) has to do with the present moment and is about the act of “reading” it, so to speak, of finding signs in it: signs of something that can't be observed with the naked eye.

The photos I use in that story—yes, I took them with an iPhone—are a blend of some images I already had and others that I took expressly for the project. I always have an extensive supply of the former because whenever I leave the house, I'm constantly on the hunt for compelling images, shots, or strange objects that I happen to stumble on. I take pictures of them as I can and archive the photos for my personal use or post them on social media. When I do the latter, I usually label them with #Apparition. To this day, I continue collecting these apparitions. So, chance played a rather significant role in the story's composition. That, and the fact that several outings during that time were to two neighborhoods in particular: the Historic Center of Mexico City, where there are more historic buildings, and Iztapalapa, which is poorer and more densely populated.

Your photos for “An Ordinary Day” and and the images projected onto the reader’s mental screen by the word-pictures in the apocalyptic “X City” destabilize perception and disturb. Some of the word-pictures of “X City,” like the seventy weevils exiting a dead woman's mouth one by one, will never leave me! And in “An Ordinary Day,” for your protagonist Horacio Kustos, a familiar image like a car’s open trunk evokes the sound of distant screaming. Such unheimlich textual accompaniment to an image reminds me of Antonin Artaud’s theater of cruelty, in which magic tricks, special lighting, and violence were used to shock the audience into looking deeper, reconnecting with their emotions and facing the horrors that lurk beneath society’s apparent order. Do the image–text combinations in Scary Story share that goal of ripping off the veil? Does this effect of literary electro-shock become more challenging to accomplish with today’s reader?

I’m pleased, if I may say so, that you were impacted by that image of the weevils because, in Mexico, there's a superstition according to which eating weevils in a specific ritual order is a miraculous cure. I mean, I wouldn’t be surprised if that imagined episode actually happened at some point.

Regarding your question, yes, it’s exactly as you say. In Mexico, it appears we’ve become desensitized to daily violence, and part of the blame lies with its more common representations, which are very attractive because they’re easy to understand and replicate; they can quickly turn into a spectacle. I aim to show precisely the feeling of rupture that happens when we are victims and not merely spectators of the terrible.

Fascinating! I didn’t know about the cultural significance of the weevils. That shows how the density of an image can be invisible to the reader (or translator) and still exert a potent, meaningful force.

In translating Scary Story, I chose to sacrifice the original character limits imposed by Ex-Twitter to free myself to express the word images as effectively as possible, prioritizing image and impact over structure. After all, Ex-Twitter’s original character limits changed, and then the platform as we knew it ceased to exist by becoming X! So abandoning this restriction was just another transformation among many. And yet, structure can also be a sign. For example, the numbered, regressive centalog of “X City” is a ticking time bomb. Do you think my decision to chuck the character limits damages the meaning of the text or its visual aspect?

I don’t think your decision was a mistake. On the contrary, an essential part of the work on this project, since its first publication (online) in Spanish, was to adapt it for print. I also made modifications to the original texts—like undoing abbreviations, adding punctuation, and such things—when I moved it from its digital publication to a text file that was useful for the book design. What you did had the same goal: to make the text look as good as possible for its next destination.

Regarding the countdown, I’m delighted that you saw it as a ticking time bomb! That’s precisely the image I always had in mind. The numbers of each section are the foundation of the structure, and I think they are easily transferable to most languages.

Yes! The countdown is highly transferable, and the numbers do a lot of work in “X City”, creating tension and implying a certain fatalism: The reader knows they’re going to get to zero, and what then!?!? They create an illusion of order in a narrative about a city devolving into chaos. Our contemporary lives are ruled by numbers—money, the stock market, the clock, even the twenty-two chromosomes in our bodies, a real number—but numbers ultimately fail to clarify anything about their predicament for the residents of “X City.” Are these numbered “signs” partly a critique of humanity’s insistence on a quantitative view of life at the expense of the unquantifiable? Like beauty, decency, love, justice, and all those mistreated values that cannot be assigned a number? Am I reading too much into this?

I really like what you read into the numbers, though my first impulse went in another direction when creating the story. In prophetic texts, from antiquity to today's conspiracy theories, there is an emphasis on regularity and order: the seer is the one who can find the “clues,” whether in the sacred text, the day’s events, or the natural world itself and arrange them to produce a coherent interpretation, a “model” of what going to happen. In “X City,” the only person who can see the countdown is the reader, and therefore, no one else understands that there's some sort of tragic destiny being enacted. Anyway, this is how I was feeling in 2014 as the news kept on coming in about the boys from the Ayotzinapa normal school, as well as many other horrific events, including those produced by Mexico’s interminable “war” against drug trafficking. I felt we were approaching the consummation of something dreadful that no one could quite visualize. That moment didn’t come, of course, but as we notice so tragically these days, we’re still sunk in the mire of violent events, a situation aggravated by discrimination and extremist discourse.

Yes. “X City” is full of “seers,” unconscious prophets who can’t grasp the meaning of the messages they view. We see, but we don't see, and what's worse is that we’re blind to our power to derive meaning from events. In “An Ordinary Day,” poor Horacio cannot simply stroll around the city because he sees too much! Everything has a sinister aspect, and, finally, there’s your face, looking up uneasily at the lens: “ . . . You really don’t recognize me? / I’m your main character.” Is this a wink at selfie culture and how we become unrecognizable to ourselves through the carefully chosen and often altered images of ourselves we promote? Would I be wrong to think that this penultimate image and its accompanying text reference the Jungian shadow, the dark part of the psyche where traumas and creativity exist but from which we tend to avert our eyes? Your gaze is so intense in this image, so direct.

Thanks so much for mentioning the topic of the gaze! It’s something I’ve been concerned with ever since I first wrote these stories because during these times we’re living in, such signs go unnoticed; warnings and alarms go unheeded because we’re all always too busy with “other things” that are either more attractive or more pressing at the moment. In a way, that’s the central premise of the plot in “X City.” As for my face and the way it appears in “Ordinary Day,” the truth is that I wasn’t thinking about selfie culture but rather something closer to the Jungian idea. Using that photo was a somewhat impulsive decision that I didn’t ponder too deeply back then. Still, perhaps it could be viewed as a sign of the splitting off of whatever we create, the way we give away a piece of the Self to our creatures (and/or the other way around, maybe). The person speaking isn’t Kustos, but rather that Other, the one who is me and not me, but who, in a way, is my character’s character.

Let’s talk a little about image fidelity and photographic technique. The photos in “An Ordinary Day” play not only with perspective, like an enormous thumb in the foreground that seems to belong to a giant, but also with focus. Some images are blurry, like the messianic figure in “Nagaoka Temple” or the woman walking away from the viewer in “Housing Unit.” But the iPhone, like all modern digital equipment, specializes in fool-proof definition and prettiness—even enhancing reality’s aspect. How much did you have to work against the machine to create these images, and what was your purpose in doing so?

The truth is that I love distressed textures: scratches, craquelure, and noise of all types. You see, I grew up between the Super 8 film and analog video eras. As an adolescent, I repeatedly watched a very poorly made copy of The Exorcist (the first one, of course, the one by [William] Friedkin [made in 1973]), and I think I liked it better than the original [print] because it looked like a home video! It had an intimate, less polished, more “authentic” quality. That experience now seems to be a precursor of the “video=reality” idea that was so relevant in the 1990s. But it also engages with works from other periods, like the movies of Czech filmmaker Jan Svankmajer, who filmed surrealistic scenes in dilapidated and half-collapsed buildings in the former Czechoslovakia. Along those same lines, in “An Ordinary Day,” I wanted to create images that didn't look overly curated. In addition to employing several techniques I found in books and articles on photography—how to focus far away from the subject, unbalanced framing, or taking the shot blindly—I also edited and put filters on some photos after taking them. Yes, it was kind of a struggle.

Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you'd like to say about the relationship between images and text in your work?

My work exhibits a strong influence from movies and comics, that is, from two visual media; the odd thing (at least for me) is that I apply that influence on the level of narrative structure. I like creating parallel flows of information with images, text, and design that share the same page as comics do and adapting effects like those applied in film editing to the page: jump cuts, raccords, different scenes, and other such techniques. A lot of them are there in Scary Story.