Tan’s body of work, like the way she approaches the things that meet her eyes, speak to her, or, as is often the case, refuse to let her in on their secrets, is explorative, observant, and contemplative. All her films—the very first few, the popular, the controversial, and the more recent ventures—display a concern with the human lives intertwined with the history of Singapore, its literal and cultural geographies, and how they impose a mark on one another. In a word, her work embodies the fragmentary and dissociative memories of a nation in flux.

The following interview was conducted over Zoom in October 2024. I spoke to Tan about her beginnings, the conundrum of language in her films, and the rewards and difficulties of keeping an archive (of images, of histories, of untold stories lost at sea). We also talked about walking.

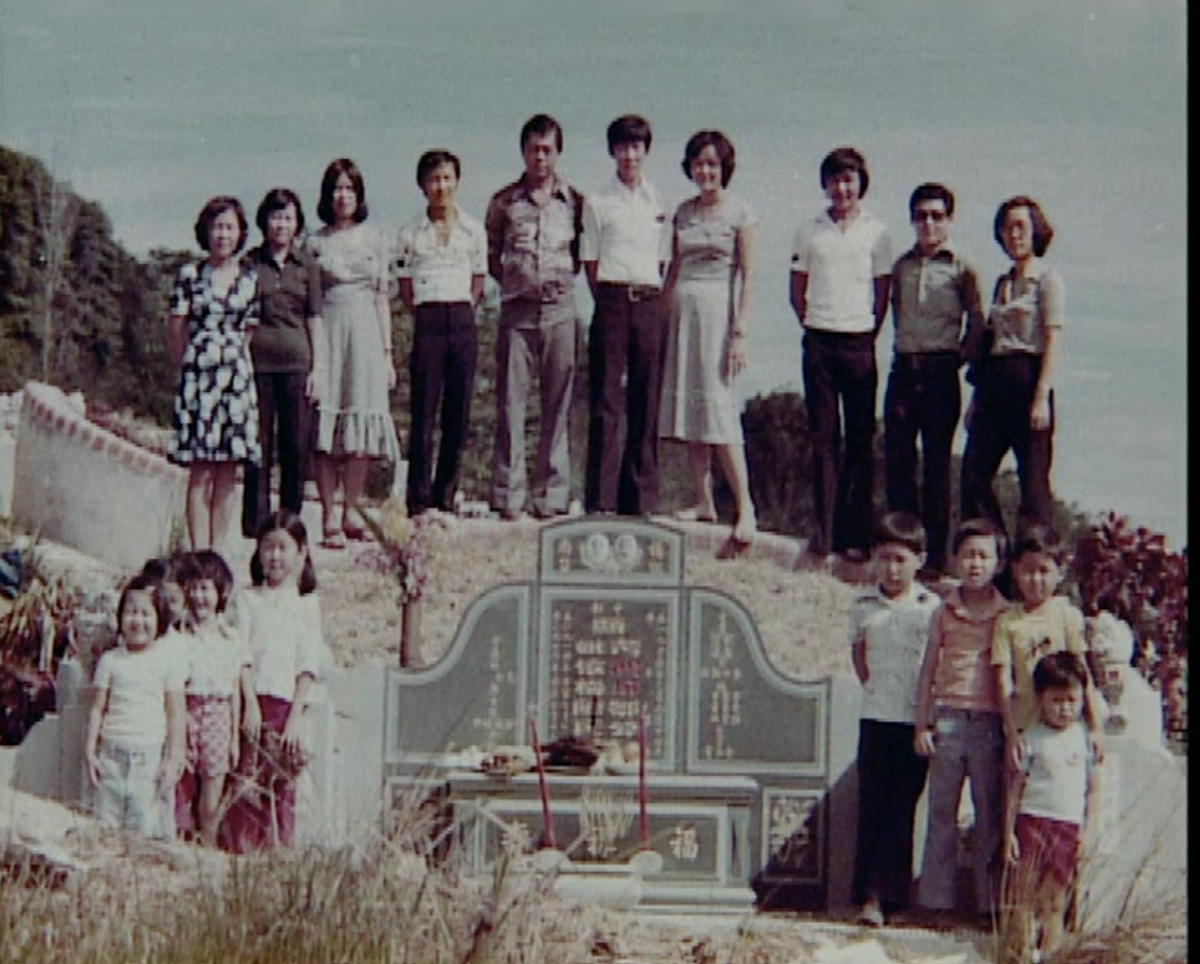

I want to begin today’s conversation by asking you about Moving House (2001), one of the films you made at the beginning of your career. It’s about one of the 55,000 families in Singapore forced to relocate the remains of their relatives to a columbarium, as the land of the gravesite was needed for urban redevelopment. What compelled you to make this film? I know that it was a continuation of your first short film made in 1996, also titled Moving House, about your own family’s experience of exhuming your great-grandparents. What did the “house” in the title mean for you?

Moving House (2001), dir. by Tan Pin Pin.

When I was in my final year at Northwestern doing my MFA, we all had to make a thesis film. And because people usually spend a lot of time earning the money to make these films, I thought, why don’t I participate in this pitch that had just been announced in Singapore to get funding? In the end, I participated, won the pitch, and got my project funded. This is how the first Moving House, the version made in 1996, came to be—quite serendipitously, actually—thanks to that pitching forum. After its release and the Student Academy Award I won in 2002, people began to regard me as a documentary filmmaker. At the time, I didn’t see myself that way, as I had only made one documentary.For me, in the original banjia (Moving House), jia, or the house in the title, is the gravesite of my great-grandfather, who moved to Singapore from Xiamen in the late 1890s. The film is very much about the first branch of my family in Singapore, so a strong sense of home was distilled into that film.

In the 2001 version, the family I covered, the Chews, also had family members whose graves were exhumed. They were also immigrants from China and used to live in the Fuzhou area. This discovery really fascinated me, because the graves all over Singapore are, in a way, the seeds of different branches of different families that settled outside of China.

Still from Moving House (2001), dir. by Tan Pin Pin. Film. Courtesy of the artist.

It’s so interesting that your first feature film solidified your position as a documentary filmmaker, because the short you made a year before, Microwave (2000), is so different.Microwave (2000), dir. by Tan Pin Pin.

Yes. I think if I had stayed in the US I would’ve made totally different films.It seems to me that there’s a sense of precarity and impermanency present in your work, as graves are dug up, buildings are constantly erected and demolished, in Singapore. How did the particularities of uprootedness affect your filmmaking throughout the years and your approach to it?

I think my films can speak more for themselves in this case. They are, in essence, my reaction to my surroundings. That’s why I said I would probably make very different films had I continued to work in the US—the themes of change and impermanence percolate through my films because I was surrounded by tension particular to the culture I found myself in. Being in the US would have exposed me to different tensions and concerns.

What specific tensions might they be?

Probably the inability to understand a lot of things. For instance, Microwave was made because I didn’t quite see the attraction of the Barbie doll, or understand why a one-dollar note would have the word “God” on it. So my films are a way for me to identify my curiosity about certain issues, the feeling it inspires in me, and then try to drill deeper into them.

You’re very interested in the mundane, the everyday, and the small gestures of meaning-making. You’re also drawn to people relegated to society’s margins who perform these gestures, like the subway station harmonicist in Singapore GaGa (2005). What are some of the delights and challenges of depicting them in documentary film?

In the context of Singapore Gaga, which is about the soundscape of Singapore, I had to approach the strangers I met on the street, like people who do busking or singing in public. Once I went down that route, I needed to consider how they’re portrayed. I think it’s important to show the full conversation between the two of us, the subject and myself, that is; it’s a way to situate us on the same plane, with equal footing. So in the film, you might see and feel the push and pull between the interviewee and the interviewer.

But there are always consequences I couldn’t have predicted. In Singapore Gaga, the lady who sang the tissue song told me that I affected her business by filming her, so I felt really bad. I apologized and moved very far back. That’s an important exchange for me, because it made me realize that the people being approached and filmed have some say in how they’re represented on screen as well.

Still from Singapore Gaga (2005), dir. by Tan Pin Pin. Film. Courtesy of the artist.

Many, if not all, of your films deal with how personal memory is situated in the larger span of collective history. And as I was thinking through this question, I found myself constantly going back to the saying that “if you can articulate it in writing, why make it into a film?” Do you see your films as a kind of visual language to express—or embalm—what cannot be effectively articulated in spoken or written language?I’m a very visual person, so for me, my main language for expressing myself would be the visual language. In other words, visual art is the medium I use to work through whatever that needs to be untangled. It might be different for different people—some would be drawing or writing, I’m sure—but I never really had the instinct to write. I might do it occasionally, but it doesn’t come to me as naturally as filming.

That makes a lot of sense. Do you write your own scripts?

I don’t really have scripts. I have ideas, a one-page treatment. Much of my work is constructed through filming and editing, because there’s no way you’ll be able to write it before it happens. But I wouldn’t call my working process “spontaneous”—the materials with which I work are just collected in a different way.

While we’re on the subject of language, I want to mention that your films are multilingual: people have spoken English, Mandarin Chinese, Malay, Japanese, and Hainanese in your films. Your subtitles, I notice, are always in English and Chinese. What role does language play in your films?

Do you mean whether the audience can access a film that is not in their native tongue?

I was thinking more in terms of your intended audience.

I try to get my films seen by as many people as possible. The English subtitles are for the hard of hearing, for people who don’t understand other languages apart from English. Mandarin, on the other hand, would be for the population who doesn’t speak English so well.

Translating subtitles is an art in and of itself. I have a difficult time doing it, because the English that is spoken in Singapore is pidgin English. If I were to transcribe the conversations in the way they were spoken in pidgin English, it would be hard for non-natives to understand, so I usually need to translate them into proper English. That always pains me, because why would you want to make the people you’re filming say something that isn’t what they’re actually saying?

I encounter similar difficulties making Chinese subtitles. Sometimes, when people speak English, they use a different kind of syntax—Malay syntax, or maybe even Chinese syntax—but they’re still speaking English. And when I got down to the actual translation, there is an extra layer of translating translation involved: do I use the English translation that I’ve imposed on my subjects to translate their words, or do I translate according to their original syntax?

Right, and these nuances, I suppose, make it hard for you to show your films to people who don’t share such a fraught relationship with both English and Chinese. This brings me to my next question: how do you see the relationship between language and your audience?

In my films, people switch languages quite often, sometimes even within a sentence. There are usually three languages involved. So for a foreign audience, I normally put the languages that people in my films are speaking in parenthesis in the subtitles, as I feel it’s very important for the audience to get a sense of the multilingual quality of a place and time. For example, if I were watching a documentary set in a Kurdish community in Germany, I would want to know which language people are speaking in, because I can’t tell the difference between German and Kurdish. And this is a crucial plot point in some cases: if people are speaking Kurdish in front of someone who’s German, we can infer that the German person won’t know what the Kurdish people are saying, but they are at least able to make a distinction between the two languages. For a viewer like myself, however, such distinction isn’t that obvious.

In Singapore Gaga, there’s a scene in which students from a local madrassa are singing in Arabic. That scene is extremely significant in the Singaporean context because the students there are Malay, yet they’re using Arabic to articulate themselves. It was filmed a few years after 9/11, too, so it has a certain tension that might only be visible to the domestic audience.

IN TIME TO COME (2017) is made up of fleeting moments distilled into the moving image, without language and exposition, yet the audience seems to be a degree further removed from the narrative. What made you opt for this approach?

I suppose I call IN TIME TO COME the Singapore Gaga of rituals and spaces. It’s filled with random spaces in Singapore that would never be recorded if it weren’t for this film. It’s possible that in fifty years they will seem completely prescient, because nobody will know what the in-between moments looked like.

Still from IN TIME TO COME (2017), dir. by Tan Pin Pin. Film. Courtesy of the artist.

Was that where your idea for this film came from? To record places before they disappear, or before they come to be what they will be in the future, or what they are now.Yeah. People will always know when a guest of honor arrives, but they don’t know what it feels like before the guest of honor arrives or even question why we have a guest of honor in the first place. Or people will know about a very famous expressway, but they wouldn’t know what it was like before it existed, which was why I filmed the day before its actual opening for the film.

Sometimes I see morning assemblies taking place in schools and have a feeling that they would still be the same in fifty or sixty years. And that’s a problem: why are some of these militaristic rituals kept? It might be because we’ve been governed by the same political party since 1959.

In that case, IN TIME TO COME can serve as a frame of reference for you to return to in the future. A marker of time without flow in a given moment.

Yes. I wanted to film rituals of everyday life that had never been previously recorded. The metaphor for IN TIME TO COME is in essence a time capsule, which is featured in various parts of the film. Some scenes in IN TIME TO COME include mosquito fogging, school assemblies, and official openings of grand infrastructure projects. For the fogging scenes, many dengue hemorrhagic fever cases happen throughout the year, especially when it gets humid and damp, which poses the danger of mosquito infestation. So people are fogging the mosquitos away.

In your work, you use archival materials such as newspaper clippings, old photographs, and historical footage to bridge the gap between the past and the present. As I’m talking, Invisible City (2007) comes to mind, for it’s a film about the desire to preserve history before it disappears so that it can be carried forward to the present. But this preservation instinct is also fraught with risks. For example, in Invisible City, there’s a scene in which a former student activist is showing you photographs of Chinese activists in 1950s Singapore and telling you that some of his photos might have to be censored. I read somewhere that after the film came out, he was approached by national security officers who wanted to look through the photos. What do you make of the relationship between the documentation of alternative, or hidden, histories and the authoritarian power to suppress such documentation?

I make documentaries as a way to find out what I’m curious about, and what I’m curious about is usually what I’m not supposed to know. Invisible City is a film about the effort it takes to not only dig stuff out—like the work of the archaeologists, in a way—but also to store as well as to make sense of what you found. I wanted to honor the labors of documentation, the labors of keeping an archive, and the labors of remembering.

So many uncertainties affect whether something is preserved, remembered, or even known. If the journalist’s photographs were lost, for instance, or if he felt too scared to show them, we would never learn about the history of Chinese activism in 1950s Singapore. There are simply too many hurdles for information to flow, to get to us.

Still from Invisible City (2007), dir. by Tan Pin Pin. Film. Courtesy of the artist.

A lot of your films deal with this issue, but Invisible City in particular showed us the process of making information available and accessible, because you saw the journalist speak.And you saw the final article that was written, which gives you the gaps that the journalist had left out in his narrative. So in a way, each of the different stories within Invisible City is plotted through: people find a bottle, but when the bottle eventually lands in the archive, it becomes a number and a familiar brand of drink we drink. It’s just labeled in a very clinical way.

Your newest film walk walk (2023) was originally commissioned for a bus terminal in Singapore. I saw it at Vassar College, during a screening hosted by the film department. You were there, too. Was that your first time seeing it on a big screen? How did the change in means of exhibition impact the viewing experience and what the film originally sets out to accomplish?

Yes, the screening at Vassar was the first time I saw walk walk on a big screen. In terms of content, it features four women homemakers who walk together every morning, and a woman who walks to think. Form-wise, it has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Since it’s also a public installation at a bus terminal, it’s meant to be legible to both regular bus passengers and filmgoers. Therefore, it’s subtitled in Mandarin and English, and conventional in its construction.

In a bus terminal, it makes more sense for the visitors to be able to drift in and out if they want to, whereas in the cinema the audiences are locked in their seats until the film is finished. In any case, it’s quite intimidating to have people’s full attention on your films. Perhaps even more so in the case of walk walk because it’s showing in two formats, and it has to face scrutiny in both venues.

The bus terminal where walk walk (2023) is sited. Dir. by Tan Pin Pin. Public art work and film. Courtesy of the artist.

Why did you choose to film the act of walking in particular, and why have it placed at a bus terminal?The spine of the commission was part of a larger commission based on a famous path that stretches from the south of Singapore, so walking is one of the primary activities that takes place there. As for why it’s housed in a bus terminal: I was trying to fold in the idea of mobility as well as the freedom of movement into the surroundings of the terminal, given that it sits next to the famous path.

Throughout my career, I’ve observed how Singaporeans interact with their country’s landscape—how they respond to their immediate environment—through the small gestures of the everyday, as we’ve touched upon, and on their own terms, by their own rhythm. I hope walk walk can offer my audience some reflections on their relationship with their surroundings and their agency in shaping their surroundings, even though the thought of which can seem impossible sometimes. We all play a part in shaping our countries. My work tries to honor that.