Sadness wakes me up.

What, already?

Sadness comes every morning to wake me,

but the hour keeps arriving earlier and earlier.

Sadness is going to work itself to death.

Sadness shakes me without a sound, watches as I awaken,

then bows politely and stays at my side all day.

Sadness lets me lie still a moment

and sings to me of what happened yesterday,

and the day before yesterday, and the day before that,

and all the days that came before.

I burst into tears at the sound of sadness’s low, husky voice.

Sadness sighs lightly and stops singing.

Then asks, what will I do today.

Don’t know . . . I mutter.

Sadness sits me up,

opens the window and folds away my blankets.

Hands me my book, answers my calls, warms the bath water.

And then, oh so carefully,

suggests maybe I eat something.

I do not want to eat the food that sadness makes for me.

When sadness follows me out the door,

I decide I will shake sadness off my tail when I have the chance,

but with each step I take back towards my room

I know that sadness will be curled up in there,

filling every corner, waiting prettily for me.

I don’t know why I was so into this poem. Was it because sadness was my daily bread? The poem doesn’t reveal why the speaker is sad. Sadness is merely the speaker’s shadow. At any rate, I read this poem for the first time that night and have been re-reading it ever since. My brother treated me to steak at Bennigan’s. That’s also where I tried wine for the first time.

“It’s okay for you to drink alcohol since I’m here,” he said.

He sounded like he was double-checking whether I was indeed a minor. That first taste of wine was sour and not at all appealing. I had no idea at the time that I would come to like wine so much.

“Do you like being in college?” I asked him.

“Yeah, it’s good. But more than becoming a college student, what I like is no longer being a high school student and having to cram for the entrance exam. And I guess now I won’t have Mom nagging me about how I have to study harder. The next three years are going to be stressful for you.”

That wasn’t true. My grades weren’t that great, but Mom never pressured me to study. Even if I had made good grades, it wasn’t clear whether I’d be able to go to college. I had no idea whether my parents would pay for it. Though I was Min-hyeong and Min-hui’s little sister, I wasn’t their real family. It was obvious that our mom treated Min-ju and me differently. She paid close attention to Min-ju’s grades but was indifferent to mine. Ever since Min-ju had started middle school, she’d been on her back about her grades, but she nagged me far more about cleaning the house and washing the clothes than she did about doing my homework. I was not my mother’s daughter. I was the Han family’s maid.

“Do you really think I’ll go to college?”

I wasn’t just thinking about my grades but also the tuition.

“Of course you’ll go. Your grades aren’t that bad, and since you’re only in your sophomore year you have plenty of time to turn your grades around. If it’s too hard on your own, I’ll tutor you.”

Min-hyeong was only thinking about my grades. But when Min-ju and I became seniors, he taught us math and English every weekend. We were basically getting private tutoring for free from him. Up until my freshman year of high school, my grades weren’t as good as Min-ju’s, but at some point in my sophomore year they began to overtake hers. And by a considerable margin, too. Nevertheless, my GPA still lagged behind hers, since my grades weren’t that great in my freshman and sophomore years. But I got a much higher score than her on the college entrance exam. It was as much luck as it was talent. The entrance exam that year was regarded as more difficult than previous years, but I did much better than I had on the practice tests I’d used to study. That’s how I was able to enter the same college as Min-hyeong. Albeit in a different department. Min-ju got accepted to the journalism and broadcasting department of a private university that was pretty much just as good.

“Min-hyeong, if I can get enough money somehow to cover just the first semester’s tuition, I’ll do what it takes to put myself through college.”

“I told you not to worry about that. And what do you mean, just the first semester’s tuition? Mom and Dad will pay for all eight semesters. Focus on your studies and don’t worry about the rest. What do you want to major in?”

“I haven’t thought about it yet. I don’t even know if I’ll be able to go.”

“Of course you’ll go. Now tell me what you want to study.”

“I don’t know, I was sort of thinking maybe literature or philosophy. Those seem kind of cool.”

“So you mean you don’t care about getting a job out of college. Guess I should’ve known you’d be just like me. Remember how disappointed Mom and Dad were when I applied for anthro?”

“They thought you could do better. Your grades were good enough to get into business or law school. You did really kind of disappoint them.”

“So, then, don’t let them down.”

“Ha! With my grades, there’s no point in worrying about disappointing them or not. My grades aren’t good enough for me to get into Ewha University, regardless of which department I try for. And besides, it doesn’t matter which department or which school I do go to. Since when have Mom and Dad ever been let disappointed by or proud of me?”

I was bold. Min-hyeong was speechless for a moment.

“It’s been hard for you, hasn’t it? It always has been. But it’ll get better once you’re in college. You could even move out then if you want.”

“You really think so?”

“If you want.”

“How could I afford to live on my own?”

“If Mom and Dad don’t help out, I will.”

“For real?”

“For real!”

His promise came true in a somewhat disjointed way. During my second year of university, when I was awarded a merit scholarship for good grades and was exempt from paying tuition, I moved out of the house and into a place of my own near the school. Min-hyeong helped me out with money. Indirectly. He bitched and protested so much at home that he made it impossible for Mom and Dad not to pay the lease on my rented room. And it wasn’t the first time he’d thrown a hissy fit on my behalf. The fact that I was able to go to college at all was entirely his doing. Up until my junior year, and maybe even right up until I took the entrance exam, Mom was more or less half-hearted on the subject of my going to college. The other family members likewise only gestured at supporting me. Only Min-hui and Min-hyeong were different. Then one Sunday evening, several months before the entrance exam, Min-hyeong went off on our mom. This is only a guess, but I think the conflict over my going to college had a lot to do with the deepening divide between them. Of course they’d never been on good terms. But that was the first time I’d seen him “rampage” against our mom—or rather, against the whole family—like that. Even when he helped me move out, he didn’t go off on them that harshly. But that night, he yelled, “You call yourself her mother? Her father? And as for you two, Min-hui and Min-ju, you dare to call yourself her family?” He even pounded the dinner table with his fists. Then he said:

“What is she to you anyway? Min-ju, don’t you feel even the slightest shred of sisterly love for Yeong-mi? She’s been a part of our family for over ten years! Okay, but fine, let’s say you have no family love for her. You’re the same age! Can’t you at least be her friend? Don’t you even feel sorry for how you’ve treated her? You’ve been sticking her with your chores all this time—don’t you see how unfair that is? Are you really such a heartless brat? Shouldn’t you be the one trying to stop our mom from treating her that way and pestering our mom to send her to college?”

Oh, how I wish I hadn’t been there to witness that! I was so embarrassed. That night, Min-hyeong called me out to the balcony and hugged me and cried. He kept saying, “I’m sorry, Yeong-mi. I’m so sorry.” That was the first time he’d apologized to me like that. I didn’t know he felt that way. Actually, that’s not true, I did know. But anyway, he’d never said it out loud before. He’d just shown it through his actions, and maybe even more indirectly. I could sense it. The day I got my acceptance letter, he was the most excited for me. He took me out to a place called Oshubal in Myungdong to celebrate.

“Now that we know you got in,” he said, “let me ask you one thing. Why on earth are you majoring in aesthetics?!”

“Not you, too! I chose it because I wasn’t sure about my grades. It was a safe choice. I’m not like you. Truth is, I wanted to apply for English lit.”

That was only half true. It was true that I’d made the safe choice, but I wasn’t more drawn to studying English lit. I didn’t exactly know what they studied in aesthetics, but something about it called to me. It fanned my vanity.

“Hmm . . . I see. But maybe it’s for the best. You’ll probably learn a lot more about all kinds of art in the aesthetics department than you would in English lit. The professors in that department don’t seem like they’re all that tough, but that’s where you come in. Just don’t waste your time in college by taking it too easy—make sure you keep your grades up.”

“Yeah, I’ve already promised myself I won’t waste my time. Given how hard it is to get a job these days, I can’t let my grades drop. But how come you skip so much class?”

“What can I say? I prefer drinking to studying. And you can learn a lot more about homo sapiens in a bar than you can in a lecture hall. The professors in my department aren’t much tougher than the ones in yours.”

“I understand why you didn’t want to go into law or business, but why anthro? It’s not as cool as philosophy or sociology.”

“That’s true, but it seemed cool to me. I wanted to learn something about people. I still haven’t yet though.”

“The truth is, Brother, I never really believed I’d be able to go to college. So I’m kind of in shock right now.”

“You could go to grad school, too. If you want to, that is.”

Of course I wanted to. But I didn’t think I could get in. At least, I knew that I probably wouldn’t be able to right after finishing college. But it was great just knowing I was a college student. All the anger I’d harbored against our mother disappeared. I felt grateful for having been adopted. At least, for that moment anyway.

“I don’t dare dream of grad school! Seriously, Brother!”

In the end, I went to grad school. I don’t have a Ph.D. yet, but I got a master’s degree and a Diplôme d’études approfondies from the Sorbonne in Paris. I did it entirely on my own with no help from my family. Well, saying I did it “entirely on my own” feels a little dishonest. I was able to afford living in Paris for two years because of help from the government. I was selected for a study abroad program for employees of the Ministry of Culture, which is how I earned my master’s and D.E.A. Before long, I’ll have my Ph.D. as well. As a matter of fact, I’m working on my dissertation right now. Since my program doesn’t require me to participate in seminars, I meet with my advisor every day. My dissertation topic is a comparison of cultural administrations in various countries that have Ministries of Culture as part of their governments, including France and South Korea. I was inspired by Marc Fumaroli’s L’État culturel, which I read during my master’s program.

“No! You have to dream big!” Min-hyeong said back then. “Besides, doesn’t the fact that you’re majoring in aesthetics mean that you’ll keep going after college? It might seem impossible right now, but an opportunity will present itself later.”

“Doesn’t that also apply to anthropology? So you’re also thinking of grad school!”

“If I were thinking of grad school, would I be squandering my education like this? I don’t even know if I’ll graduate. I’m just saying for you to be different. Don’t be like me.”

“You have to try harder. You could be the best no matter what you choose to study.”

“Thanks for saying that. But the truth is that you’re a much better student than I am. If I’d been in your situation growing up, I don’t think I’d have even made it through high school.”

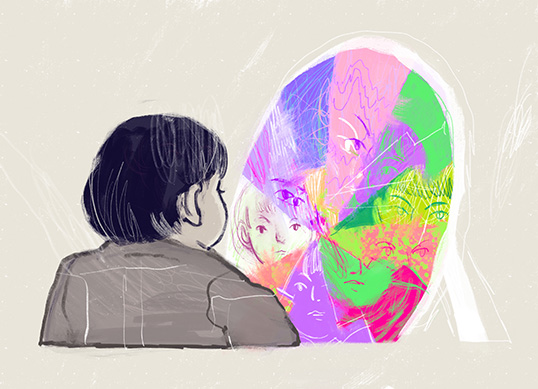

When he said that, the last ten years or so flashed through my mind like a kaleidoscope. It made me love him even more and feel even more thankful to him.

“If it weren’t for you, I would never have been able to go to college. You know that, right? Thank you, Brother.”

“You keep thanking me, but I’m not the one paying your tuition. Our parents are. So if you’re going to thank someone, thank them. But don’t thank them too much. After all, paying your child’s tuition is supposed to be a given in this country.”

“Yeah, I’m thankful to everyone. To Mom and Dad, and to Min-hui.”

“Oh, hey, when does Min-ju find out?”

“Tomorrow. She’ll get in. She played it safe, too.”

“Right. It’s better to aim low than to have to retake the entrance exam next year.

“Are things okay between you and Min-ju?”

“Why wouldn’t they be okay?”

“She’s been mean to you ever since you two were kids.”

“We’re okay. But, Brother, can I ask you a dumb question?”

“Let’s hear how dumb it is first.”

“Who do you like better? Me or Min-ju?”

He laughed out loud.

“That’s like asking a baby that’s just learned to talk whether it likes Mommy or Daddy better! So I’ll give you the same answer: I like you both equally. Min-ju is a little more immature than you, but sometimes that’s cute.”

It wasn’t the answer I wanted to hear. But how could he have answered any differently?

“Well, at least you didn’t say you like her more!”

“Of course not. I like you both the same.”

“Sure, I’ll believe you.”

After moving out on my own, I stayed away from home as much as possible. I only showed my face at holidays and birthdays. I saw Min-hui and Min-ju once in a while, but not at the house. I hung out with Min-hui more. We’d go to the same hair salon or to the same sauna. One day we were at the sauna when Min-hui asked me a weird question.

“Do you like Min-hyeong?”

“What’re you talking about?”

“Just what I asked. Do you like Min-hyeong?”

“Of course I like my brother. I like you too. You’re my sister.”

“But you’re really attached to him, you have been ever since you were little.”

“Am I? I’m attached to you too.”

“Yeah, that’s true. But you’re more attached to him.”

“I don’t know, Sis.”

I was lying. I had been attached to Min-hui ever since I was little, but I was definitely closer to our brother.

“When I see the two of you, you don’t look like brother and sister, you look like girlfriend and boyfriend. I never noticed when we were younger, but now that we’re grown up, it hit me that you two look like you’re dating. The way you two care for each other isn’t normal.”

“Sis, really! What’s so abnormal about a brother and sister caring for each other?”

“I know there are plenty of brothers and sisters in this world who don’t care about each other, so it’s fortunate when they do. But from what I’ve seen Min-hyeong has always favored you more than Min-ju, ever since you were little.”

“Whatever! I asked him once who he liked more, me or Min-ju. He said he liked us both equally.”

“He had to say that.”

“Who do you like more, Sis? Me or Min-ju?”

“My answer’s the same as Min-hyeong’s!”

“Lame!”

“You’re the one who’s lame!”

Truth be told, after moving out, I saw a lot of our brother. When I started living on my own, he had just come back from his army service and had returned to school, so we saw each other on campus pretty often. He would even stop by my rented room. At one point I thought I loved him. No, I did love him. I mean I was in love with him. It’s not like we were related by even a single drop of blood, so what was the harm in us dating? But he never saw me as anything more than his kid sister. Perhaps he did really love me, but it was a brotherly love. When we were teenagers, he would sometimes kiss me on the forehead or hug me really tightly. His warmth towards me misled me into thinking he had romantic feelings for me. But I was only ever his kid sister. Today I dropped by the publishing house and gave him a red tie for his birthday. He acted overly excited and grateful. But he wouldn’t have much reason to wear the tie. He never was the type to wear a suit.

“Should I come by tonight?”

“Better not. Min-ju isn’t coming. If you’re the only one who comes, the rest of the family will feel hurt.”

“Okay. Feliz cumpleaños!”

“Gracias, hermanita mia!”

There was a book sitting on his desk. A translation of a foreign novel called Une famille heureuse. I flipped through the pages and opened somewhere to the middle.

The only thing Didier loves is Véronique. Didier is not all that fond of Ellen or Pierre. It is the same with Véronique’s siblings. Didier regards them as unsophisticated. Didier did not grow up in an entirely different class background than his wife’s family. In the grand scheme of things, both families are petit bourgeois. But Didier received a superior French education. He was not simply a young diplomat with a bright future ahead of him but a distinguished Sinologist who’d gained academic recognition. Didier’s influence over the French government’s policy toward China was much greater than his official position within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He had even held several private audiences with the president in Élysée Palace. The president himself acknowledged that Didier was the country’s foremost expert on China. His plan after returning from his assignment in Paris was to leave the foreign service and try for a position in the lower house of parliament. Didier was a young man with ambition. He wanted to be prime minister, and deep down he even harbored a dream of becoming president. Though he wasn’t sure he’d ever be president, becoming prime minister was not impossible, he thought. His confidence in the presidency had earned him many enemies (including Minister of Foreign Affairs Jean-Paul Colombani), but he’d also made a lot of friends. Those friends were not only in the foreign ministry but were spread all through the upper and lower houses of parliament. Didier regarded his wife’s family’s French as quite unrefined. It wasn’t just the words they used. They even had a slight accent like the immigrants living in Montreuil and in the twentieth arrondissement. That accent grated at Didier. Strangely though, Véronique had no trace of that accent. Her French, like Didier’s French, was perfect “sixteenth-arondissement French.” Didier inwardly acknowledged that it was snobbish of him to judge people by their accents. But that was just part of the savoir-vivre that he’d learned from his father when he was young. If you’re not going to speak sixteenth-arondissement French, then don’t bother speaking French at all! That was one of his father’s rules. You may be petit bourgeois in class, but you must be bourgeois in culture, or better still, aristocracy! That, too, was another of his father’s teachings. Didier’s family spoke the most refined form of French. What was more, when they were among the upper class, they deliberately used the vocabulary and syntax of the elite form of French referred to as “NAP.” For example, instead of a vulgar phrase like “extremely wealthy,” they would say something more elegant, such as “getting by.” “Frugal” instead of “a terrible cheapskate.” “Their family is not blessed” instead of “their kids are doing drugs.” “She takes after her father” instead of “what a dog.” “A gift from heaven” instead of “newborn baby.” “Unfortunate” instead of “his wife cheated on him.” Didier avoided the words “Jewish” and “Muslim” entirely. When he had no choice but to speak of them, he would say “Israeli” and “immigrant” instead. His pronunciation of the preposition “de” was barely discernible, and certain names were replaced with cute (or sometimes contemptuous) nicknames. Jean-Baptiste became JB, Marie-Eloise became Marielo, Pierre-Édouard became PE, Bénédict became Bene, Pierre-Henri became PH. He avoided colloquialisms as much as possible, and particularly enjoyed employing the conditional mood. In the Dupier family, Véronique was the only one who spoke Didier’s refined and snobbish French. Ellen and Pierre, who’d spent most of their lives in the nineteenth and twentieth arondissements, were more familiar with the stimulating French spoken by those around them, the workers and the communists, rather than Didier’s high-class French. The French that divided the world into a Manichean dichotomy, that ”cowboys” or “warmongers” or “reactionaries” instead of that preferred “indians” and “peaceniks” and “progressivists” to “us.” Ellen and Pierre had almost no cause to use that form of French, but nevertheless it felt less foreign to them than Didier’s bourgeois French. And after all, Didier thought, splitting the world into two was not just characteristic of communist French but also of NAP French. Whether in error or not, that was why Didier said “those people” instead of “poor people” and “us” instead of “wealthy people.” Whenever he used phrases like that, Ellen and Pierre felt somehow uncomfortable around the son-in-law they were so proud of. Didier was bewildered. The simple French of his in-laws, with their occasional misuse of grammar or sudden resemblances to the style of the comedian Alain Percy, sometimes struck him as hopelessly unsophisticated. It grated at his eardrums. More than their actual class difference, their linguistic class difference was so great that Didier was unable to regard his in-laws as family, as true family.

My sister-in-law is a lucky woman. Lucky to have married someone like my brother. Other people might consider theirs an unlucky marriage, but if there’s one thing I know for certain it’s that my brother really loves my sister-in-law, and that he will continue to love her. Sometimes I feel jealous of her. After my brother married, I stopped spending as much time alone with him. I get lonely from time to time. I guess that means I’m old enough to start dating. I wonder if Min-ju is seeing anyone.

In some ways you could say that Min-ju is my closest friend. Between being saddled with housework up until my sophomore year of high school, and then studying my butt off after my junior year so as not to fall behind, I didn’t have any room to make friends. By that I mean I had no room in my schedule but also no room in my heart. It wasn’t until after I moved out on my own that I became close enough to Min-ju to be able to open up to her. The fact that we had to share that tiny bedroom was probably one of the reasons she felt so hostile towards me. When we were in the eighth grade or so, Min-ju invited a friend from school over to the house. I was hanging blankets to dry on the veranda when I heard the front door open and stepped into the living room. Min-ju was all smiles when she came in, but the moment she saw me her face turned red and she coldly ignored me. Her friend nodded in my direction and asked, “Who’s that?”

Without a word in response, Min-ju took her friend by the hand and led her into her room. I mean, the room Min-ju and I share. She was probably embarrassed by my scullery maid appearance.

The first time I met Min-hui, Min-hyeong, and Min-ju, I was dazzled. I felt shabby standing next to them. They looked so glamorous, the kind of kids you see on television or in children’s magazines. The girls were like white lilies, the boy was like a prince. Meanwhile, I was a short, chubby country mouse. When I look at the family portrait we took back then, I was an ugly duckling in a family of swans. But time changes everything. Now when I look in the mirror, a woman every bit as good as Min-ju—or no, much more sophisticated than Min-ju—is looking back at me.