In the beginning was the rage. Forever roaring and breaking me apart from the inside. Without it I never would have entered this unmarked path, cutting through the wilderness. It’s like mounting the crest of a wave. Riding it. Sinking. My being split apart and dissolving itself. A mossy, green stone made of an age-old loneliness rolls from my chest to my throat, from my throat to my chest. Scratchy and rough, it won’t come to a stop, I cannot regurgitate it; it regurgitates me. With disgust. I am the disgust. The disgust that spits me out and leaves me to slither all the way here.

My rage is not only mine. It doesn’t come from the wounds that have been open for centuries, shooting merciless reminders of how I am viewed: with contempt and suspicion, as someone who is always out of place. “Nappy-haired Black girl, go back to Africa,” my classmates would shout at me during recess, in front of the plaster bust of our “Founding Father” José Martí and framed portraits of Che Guevara and Fidel Castro.

Was Africa supposed to be home, then?

For a long time, I believed that uprootedness and errantry were inherently etched into my DNA. My seed was planted in the displacement of my African ancestors, for whom it was impossible to regard as their own the very land where they endured their existence as enslaved people—the territory they were coerced to call home and worship as their homeland.

I thus grew up longing for wandering: to live without limits, free from the limitations of my skin, of language, culture, and wealth. I wanted to dissolve in the waters, I dreamed of living in a place where I could walk around carelessly, and not feel like I’m walking on fragile glass, measuring each step. That imaginary place could eventually be my home, where I wouldn’t feel constantly watched by people who don’t even know me, or maybe do not even exist. All those gazes! First, those of my protective mothers, aiming to make me appear impeccable so that no one could ever embarrass me. And then, hovering above their benevolent gazes, was the ubiquitous apparatus of surveillance of every country where I have lived: immigration officers, security cameras, impertinent drones, doormen, and receptionists. And there have been the inquisitive stares of schoolteachers and professors and deans and provosts at universities, of my classmates and colleagues, all wondering what I could possibly be doing among them, with my very very very dark body. It felt like everyone was scrutinizing and judging me even if, when I turned around, there was no one in sight. Only the shadows of a judgment in permanence weighing over a Black woman. Anyway, I can’t manage to shake them off.

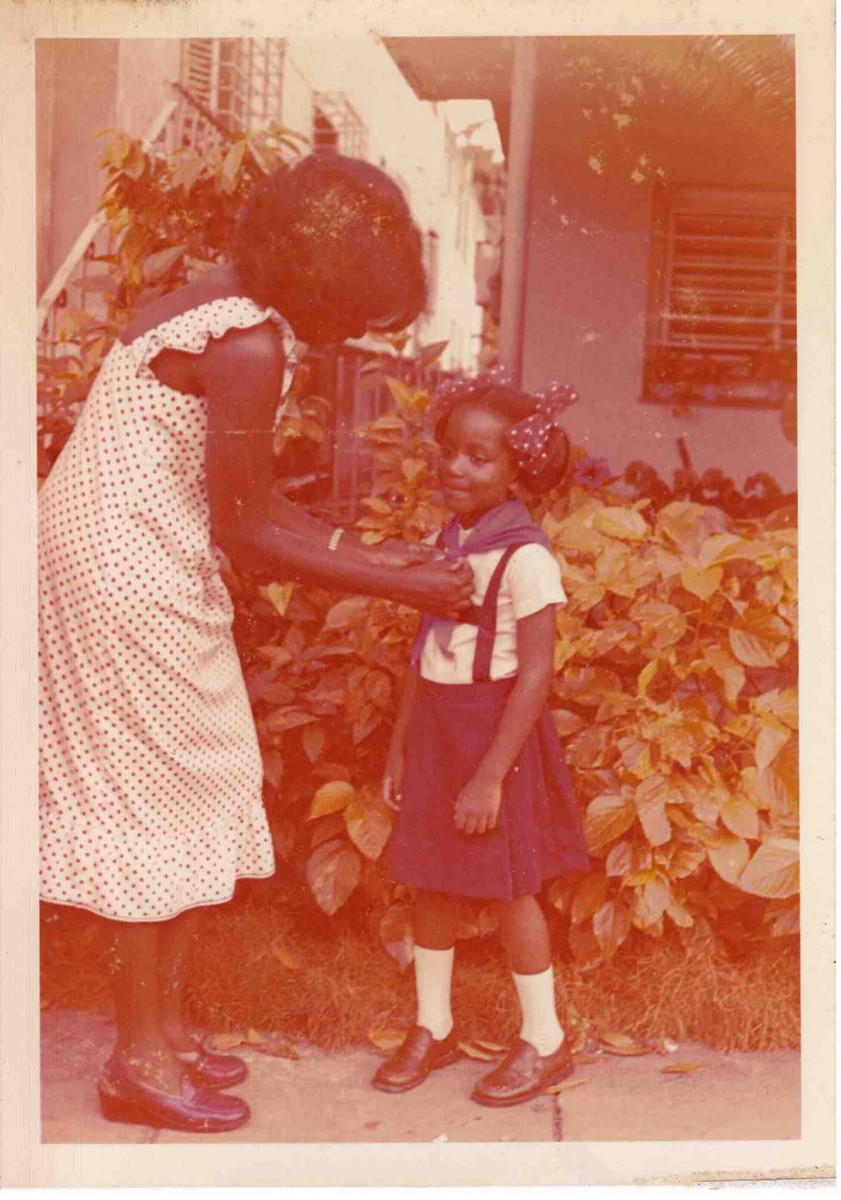

I see him again: Yosvany—the tallest, the funniest guy in the third-grade class—untying the silky ribbons that my grandmother Cecilia carefully braided into my hair every morning. Red silky ribbons with white dots bought by my father in Moscow, where he was regularly dispatched to negotiate commercial exchange contracts with our socialist comrades. In the early years of the Revolution, the government sent my father to study engineering and economics in Hungary. Swiftly becoming fluent in several Eastern European languages that I never managed to understand, by the late 1970s he had been appointed to one of the offices overseeing the country’s economy. My father would return from those trips to Eastern Europe with contracts ensuring the island’s subsistence, right in the middle of the Cold War when Cuba was isolated in the Caribbean, cut off from the rest of the Western Hemisphere; and his suitcases would be bursting with clothing and shoes for everyone in the family. But no matter how impeccably dressed and groomed I was, my classmates would always make fun of me, threatening to send me back to the Congo.

I would have liked to respond by sharing the story of the Yoruba woman who was my grandmother’s great-grandmother. I would have liked to tell them that, ultimately, if I were to return to some original site it would have been to a place called Casimba, in Cuba’s Eastern province of Guantanamo, at the foot of a ceiba tree where my family has decided that our history begins. But how can I defend myself when I don’t even know if the stories my grandmother told me were true or just a product of her imagination?

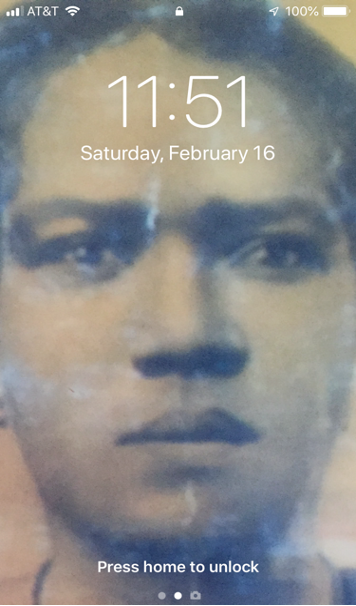

the gaze of my great-great-grandmother reaches out from the phone screen, piercing through me. The photograph was taken in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, but we couldn’t say for sure. No one in our family ever could. We are left grappling with the uncertainty of our origins—unable to pinpoint where exactly in Africa our foremothers and forefathers were abducted, how they lived before being forced across the Atlantic to begin their new life as non-women, non-men. There are no accurate names, places, or dates. We have only the memory of the flesh.

Like a Byzantine icon seeking divine perfection, my great-great-grandmother’s portrait was meticulously crafted. I am certain it was captured so that more than a century later, she could watch over me with every tap of my fingers on the phone. Her eyes carve a channel between my present and her gods, our gods, who have guided us through survival. Its preciousness invokes the power of the orisha Elegguá, from the door of the house propelling us to venture across forests and oceans.

“She was the last slave in the family,” Cecilia told me. “And she left just as she came, through the ocean. Your great-great-grandmother took the path leading to the creek, but she didn’t stop there, she kept walking alongside it, the closest she could get to the water. And, when she couldn’t see it, she used the sound of the current as a guide, following the path to the sea. Although surely she didn’t have an exact notion of the sea. What remembrance of the ocean could someone have who, back in Africa, had never seen it before being thrown into the belly of a ship along with other enslaved men and women, her friends, and her enemies, all of them tangled up together as God had so inexplicably deemed? What could the sea mean for a Yoruba slave?

I close my eyes and I can see my grandmother’s grandmother fleeing into the wilderness. I see her as she sees me darting through airport corridors, looking for a home that doesn’t exist. I see her and we smile at each other with an uncertain grimace, halting our frenzied runs. From the wholeness of my flesh vibrating under the eternity that binds us, I stretch out my arms and embrace her. And I know that only then, under the embrace, did my ancestor fly home.

So much wandering.

I have lived more years in Europe and the United States than I did in Cuba. After I left Havana in the 1990s, at the cusp of the devastating crisis that lasts until this day, I jumped from Paris to New York to the suburbs of Connecticut and then to Philadelphia. But in all places throughout the world, I am always covered by the same dark skin. Always Black, though never the same Black woman.

I am done with running away. I already know that I can’t get anywhere by hiding. There is no escape. Only a solitary path, winding into the innermost recesses of my self. “Don’t you know that the only journey that counts is the inner one?” I pick up the question that was an order, thrown by Victoire Élodie Quidal to her granddaughter, Maryse Condé. And I feel—I feel, more than I see—my own grandmother Cecilia, every afternoon spending hours on her balcony, sitting in the sun, utterly still; me watching her, but unable to disturb her reverie. In those moments, she appeared distant, lost in her inwardness, perhaps journeying to meet her Maroon great-grandmother somewhere in the infinite. The sun didn’t seem to bother her. Nothing and no one mattered in her periods of quietness. The rare moments when she wasn’t busy preparing my lunch, laundering my school uniforms, or hot-ironing my unruly hair while recounting the legend of her grandmother who mysteriously flew back to her native Africa. The only hours of the day when I escaped reprimands for my ashy elbows or sweaty face. Now I understand that my grandmother’s disinterest in my appearance was only possible if we weren’t sharing the same present. No, she wasn’t truly there. Even as I watched her motionless figure on the balcony, basking in the sun. Unreachable. Disappearing behind her time away from the time. Alone.

We crave silence, the quiet flame that, as it bursts into our submerged worlds, without the slightest commotion, burns what it finds in its path. Destroying everything, yet forging newness. When we stand still, we remove ourselves from the productive chain to which Black women have remained bound since the very beginning of our existence in the Americas, as much as from the structures sustaining such systems of supremacy. We venture far away from the world, deep into the forest where the maroon woman no longer hears the bells of the mill dictating the rhythm of work and rest, liturgy and procreation, life and death. We journey towards the inner wilderness where our quiet bodies can devote every hour to crafting and weaving the tapestry of our lives. It is the time and space of silence engendering the poetry we need—the poetry that unearths our power to conceive the “ideas which are ( . . . ) nameless and formless, about to be birthed but already felt,” as Audre Lorde wrote. Silence nurtures the calmness that invites poetry, allowing the mind to meander and discover new realms of imagination often left unexplored by conventional knowledge.

Alone I walk, following my path toward my grandmother Cecilia, she herself gone to join her own grandmother. Alone now, I approach the task I could not fulfill years ago while Cecilia still breathed: to drag a stool, sit beside her in the sunlight, and learn to embrace my suppressed self, perhaps even beginning to love myself. I bid farewell to the world and step into my own realm. Free. Accountable for what I think, do, desire, and abandon, for my fears and my power.

I am home.

When Black women commit to fully living within and for our bodies, we become ourselves. We render our humanity too eloquent to be stifled, as we find the inner peace freeing from the external expectations that define us solely by our actions and roles for others.

“Leave me alone” could be the anthem of the marooned Black woman. Let us then chant with Angelamaria Dávila:

déjenme sola en el baño con mis pestes

mis escreciones, mis intimidades. déjenme . . .

sola en mi cuarto al desvelo

alucinada y llena de llagas, o

ardorosa o aullando.

( . . . )

impúdica y maldita; en viaje

a salvarme o joderme; acosada,

sitiada por el cerco de marcas de carimbo en el pellejo.

déjenme por la calle pensando en lo que se me antoje

dándole mordiscazos al aire. no me sujeten, ahora

voy a cojer El Monte.

( . . . )

no me hablen, no me miren; por lo menos no grito

déjenme sola, coño

déjenme con mis pestes

DÉJENME QUE ME JODA

—que esto pasa—

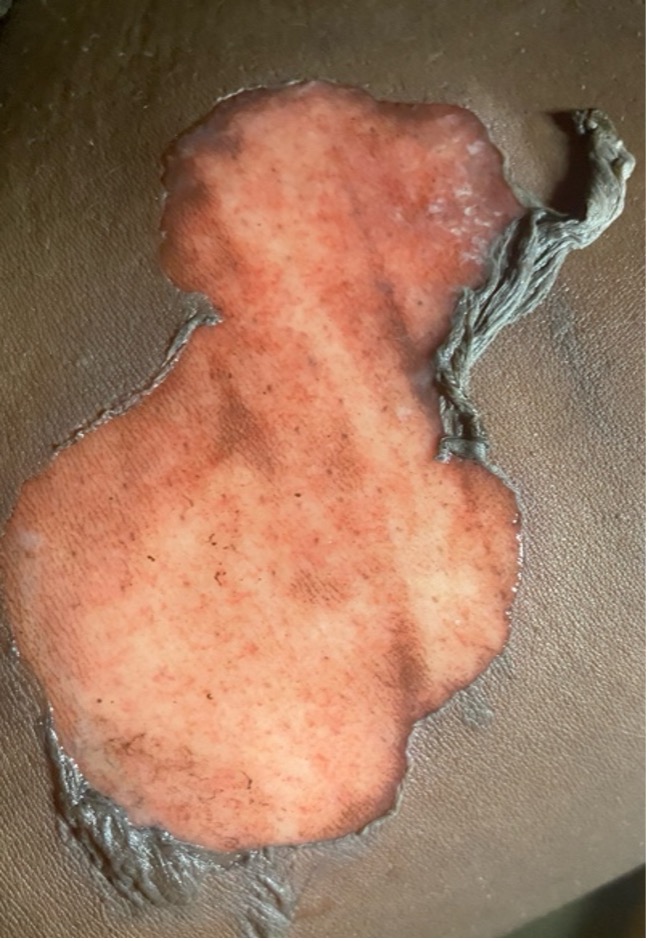

Everything goes away, yes, but before it does, a very slow process of rebirth unfolds, unannounced. The teapot slips from my fingers, its contents spilling onto my body as it travels to the floor. Screams piercing the air. The neighbor next door rushes to my aid. Hours in the ERs of two different hospitals, followed by weeks of grappling with partial paralysis. Alone, by myself. Just me and the burn, a drastic call to order from my flesh.

One, two seconds? A quart of scalding water cascades onto my right thigh, instantly erasing all plans from my calendar as searing pain clouds my thoughts. Hours pass in quiet observation of the intricacies beneath my skin. My sole task became to keep my eye trained on the miniature world thriving beneath the scorched flesh. There, tissues and fluids obey laws we, as humans, often overlook or choose to ignore—laws we have not authored yet depend upon for our existence. And our detachment from the biological marvels keeping us on our feet is what distances us from everything: from our bodies, our flesh, and all possible or unimaginable universes.

“It is necessary to delve into oneself since the secret is not to go outside, but to enter within,” Victoria Santa Cruz said in a little book I was reading in those days. When the boiling hot water consumed the skin in mere seconds, it opened a portal to my inner worlds, where, as Victoria also said, the real battles are waged without witnesses or applause. Like Victoria, I heeded my internal rhythms at last. Surrendered to them. Surviving.

The time of the flesh is distinct, marked by the intensity of pain and the hope that accompanies each new millimeter of skin gradually resurfacing. Everything can reemerge, even burnt flesh. I would be reborn anew.

And it dawned upon me that everything was already there, inside me. Pain does not overpower me because I am the pain. And life and death. A piece of skin on my thigh is pulled away, like an old curtain, but slowly, following the rhythms of my atoms, it comes out again and I observe their serene dance and celebrate both the shedding of old skin and the emergence of the new, from hour to day, week and month. It is not the world that generates my emotions. It is my hearing, my taste, my touch, my smell, and my sight, which start from me, which are in my body and produce sensations. Everything, the wondrous and the demonic, exists in me. And then, quietly taken by my senses, I shed all fear, realizing it to be the true malaise. Not the second-degree burn caused by the scalding hot water spilled on my right thigh, but the fear spread all throughout my body, which disconnects me from the lump of flesh I inhabit. I reached for Victoria’s book: “I knew the taste of connection, the taste of silence.” And I drift away within myself, until I firmly plant my palenque in the wild territory of my Black flesh.