있잖아. 어쩌면 사실이였을지도 모른다. You know. It might have been true.

And then, a soothing cold where I feel my liver taken from me and a shuddering relief, a warmth washing through me.

*

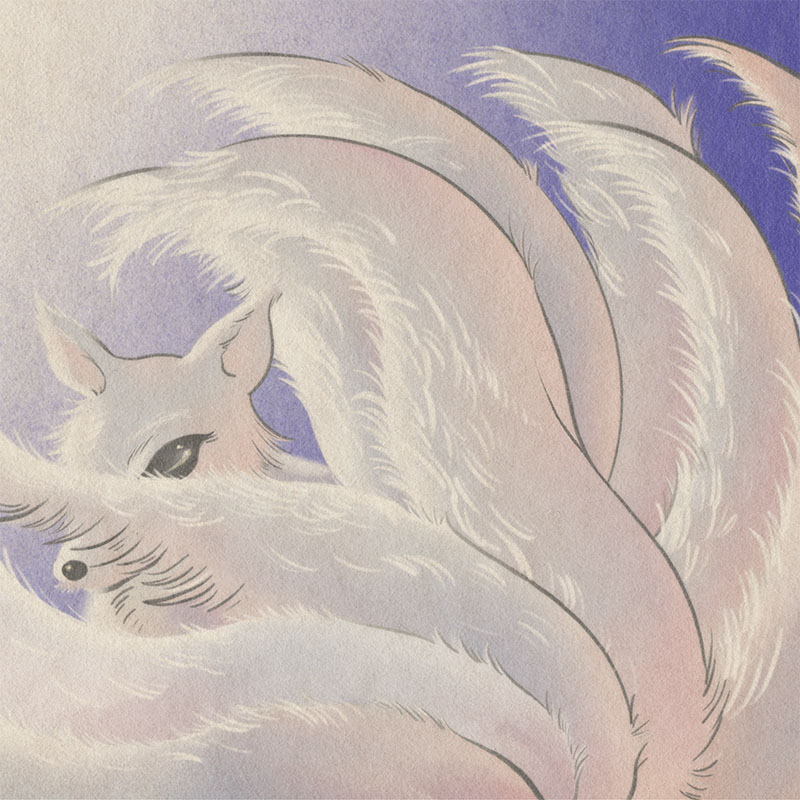

The night I first saw the fox it was misty. The dew in the air smeared the lights across the all-too-green grounds, blurring the vision in my already bloodshot eyes. The fox—she, I knew immediately—sat in the archway of a corridor across the grass. She was still. Then, (perhaps it was a trick of the light?) she swished her tail, so indulgently full that it might have been many, rather than one.

Dusk had set moisture into the grass and eaves of the university buildings as I exited the church. We had sung the service well, and the others had, yet again, disappeared with a fading tinkling of laughter and a casual abandonment of the tasks left behind. As ever, the chaplain gave me a firm pat on the shoulder, a silent delegation of the aforementioned abandoneds. Napkins and cups in the pews, dust that had sparkled in the light through the windows during service and had since been grounded on the linoleum floors for me to sweep up. The light was gone by the time I had locked the little chapel and exited the building.

At the threshold of the chapel, I stepped off the stone steps and onto the damp grass in the direction of the fox. She looked at me.

I wondered if anyone in this school had observed me this way since I had arrived. Girl who sweeps up after service. Girl who retires to her room, girl who studies well. Girl with dark hair, girl with almond eyes. If they did, they never said anything. Summers at grandmother’s—halmeoni’s—house, in the Jecheon village cradled between two mountain ranges, people told you when they noticed those types of things. 여우상아, 탔네. Fox-face, the sun’s darkened your skin.

Little Seon-a’s grandfather at the corner-shop would only give a second’s once over before he’d speak. What have you been up to? is what he was really asking, as he rang up a soft-serve from the ancient cooler and a pack of cigarettes that he’d keep secret if I sat on the back step and smoked one with him.

이런거 니같은 여자애 피는거 아니재. This isn’t the sort of thing a girl like you should be smoking.

He’d mutter, nicking a light off me.

이런거 할아버지도 피시는건 아닐텐데 . . . It isn’t the sort of thing a grandfather should be smoking either . . .

Show him a dimple, and the crinkle in his brow would crack into an uncertain, then boisterous, smile. After all, these observations were an invitation to speak.

Here, there were no such things.

I was walking closer and closer to the fox, the moisture from the lawn slowly seeping into the cotton of my socks. She remained still as stone until I was about a pace away. I crouched down. She was a very beautiful fox, eyes and nose very black, and teeth glinting very white in the lamp light. As if in a trance, I reached out to touch her fur, rippling as the lights blurred my vision yet again. She moved very suddenly then, jerking her snout to one side, baring a canine. I was struck with a sudden and acute fear; I was just a human and this was a wild animal. 아가야. 만지지 마라. Child, don’t touch.

I fell back on my haunches, heels to the floor. I wrapped an arm around my knees.

What?

원래 남을 함부로 만지는게 아니지 않습니까. Isn’t it rude to touch a stranger?

I thought of the chaplain’s hand on my shoulder. I nodded. Alright.

Why are you Korean?

그러게. Why not?

I thought she smiled at me. I sucked on the hot end of a cigarette and the smoke filled my brain, making it cloudy as the night mist was in our cross section of lamplight. My legs had begun falling asleep, knees tucked into an arm and heels against my butt. I stood abruptly.

Well, nice to meet you unnie.

Mustering up a breath, I stepped over her small body and carried on my way through the corridor and to the other side of the quad. I did not look back until I was at the far diagonal to where I had met the fox, but when I turned back, breath bated, she was gone.

*

The girl I sang next to in the university chapel was Ruth. In spite of her namesake, humble servant of harvesting (as in harvesting of napkins and cups and dust) she was not. Standing at attention in the upper left of the chapel, the afternoon light made glitter of the peach fuzz on the delicate curve of her cheekbone from where I stood, just beside her, one pace back. I watched the muscles in her cheeks, the shadow of a dimple, contort themselves elegantly as she threw her soprano notes up above and over into the rafters.

Ruth became my first and only friend at that school the second time we met for service. She had not remembered my name, but I had remembered hers. As an apology, it seemed, she had linked her arm through mine, and in one fluid, warm moment, our hips were pressed together. On the hot August and September Sundays when old men snored loudly in the pews, she’d squeeze our palms together, digging fingernails into the back of my hand to prevent the giggles from bubbling up liquid in her throat, not letting go when sweat beaded through our interlaced fingers. Then I’d smile, watching the shadow of her dimple contorting in her cheek as she bit it, to keep the laughter clamped deep down.

Sundays were a ritual comfort that year of unfamiliars, that year (exactly my second cycle around the zodiac) of the rabbit. I came to expect the low hum in my stomach that came from Ruth. Ruth who liked the Book of Psalms and made a perfectly practiced, perfectly throwaway expression of distaste when the tips of my fingers were stained with cigarette ash and whose shampoo smelt like a green apple detangler used for children with hair like corn silk like her, like the child I imagined she must have been.

Then, inevitably, when she disappeared through the chapel doors before I’d finished clearing the pews, I knew that the fox would be waiting for me opposite the quad, just barely illuminated in the glow of the chapel lights at dusk.

The fox and I met every Sunday. I started bringing her the snacks that my grandmother posted to the pigeon box that was designated as mine when I enrolled. Muktae from Pohang, dried myulchi from Gimhae, sticky yakgwa from Jongro, dried sagwa from Jecheon.

The fox liked yakgwa. As she worked her canines over them in her fox-like way, she’d brush her tail against the tip of my chin and allow me to stroke the silky fur of her back.

언니, 성함은 . . . ? Older sister, your name was . . . ?

기억이 안난다네. Seems I don’t remember.

She told me once. Only, she was certainly an unnie. Though I never asked, the word fit like it belonged in the space between my tongue and my soft palate, and in the arms breadth she mostly kept between us. Though I told her my own name, she never used it, choosing instead to call me 아가—child.

I eventually became certain that the fox-unnie was what we called a gumiho, a realization that came one particularly clear night when a particularly illuminating streetlamp revealed that the ever-bushy tail that the fox-unnie toted was in fact many, rather than one.

I was familiar with the gumiho. She was, after all, a well-worn folktale. A succubus-by-day and a fox-by-night, she was at turns seductive and cruel, stealing human livers for the pleasure of the hunt, then again ascetic and tortured in her attempts to return to humanity.

아가야. 저 소리 들리니? Child, do you hear that?

I used to press my then-compact body into halmeoni’s as we’d press our backs deep into the old ondol floors of the old family home as the wind and cold cried outside.

저 우는 소리, 아가야, 그게 구미호의 우는소리다. That crying sound, child, that’ll be the sound of the gumiho crying.

As halmeoni told it, those blustery nights, there was a gumiho, the cursed nine-tailed fox spirit, that roamed our very own and very provincial mountains and creeks. In Jecheon, you might even feel her gaze on you when you stood at the thresholds of the old hanoks that speckled the deeper part of the forest. She was once, she said, generations and generations ago, a fox only in that she was the wife of a magistrate.

그녀는 빛났었지. She was like light.

Halmeoni would say, and her own eyes would glint as if she were remembering the woman herself.

Like all glimmering women, she was the object of great admiration. For that sin, she was eventually committed to the town’s magistrate, as unimaginative as his status would imply. But how could one cage light? Though I never heard halmeoni finish the tale herself, it was passed down through lips in houses and then in streets among children.

They say he drowned her, in the river running through Geumsusan peak, enraged by jealousy and made mad by her refusal to be captured. I always wondered, then, if she were reborn as a gumiho, would it be to exact revenge? Or would it be just another injustice in a long line of them?

How could he expect to trap a wild animal in the first place?

언니, 내 간 안훔쳐 먹을거지? Big sister, you wouldn’t steal my liver, would you?

The fox-unnie pressed a sharp canine into the soft flesh of my lower belly, all aglow in the incisive lamplight of that revelationary night. I watched as the skin gave way gently, tenderly against her delicate pressure. Then, I watched as she pulled away, leaving the ghost of a mark.

In any case, it’s not such a fair question to ask is it?

언니도 그런 사연 많은가? Big sister, is your story so unjust too?

*

It was a very cold day in March, spring not yet having broken winter’s back, when Ruth hung behind after service to watch me sweeping the floor. The movements felt suddenly robotic under the presence of her attention.

Do you have stuff to do after this?

No.

What do you ever do after stuff?

What?

You know. Like where you eat, what you eat. What you do when you’re bored. I don’t know? I feel like I don’t know anything about you.

Ruth knew more about me than most people here, I thought.

I’m sorry.

I didn’t say it so you’d apologize.

She was looking at me very intently now, more than I had ever noticed her doing before. The furrow in her brow was an intruder, betraying the usually perfectly casual, perfectly noncommittal flicking of her gaze. What was she seeing? She ought to simply comment her observations, spit them into the air between us for me to see, taste.

I resumed my sweeping.

I might go see my fox later.

Your fox?

I smiled, as if it were a joke. More out of obligation than anything.

There’s just this fox, it hangs out in the quad nearest the chapel. I go by and take it things to eat sometimes. It—she, I call it, she’s like a little friend.

Then Ruth laughed. Like I thought she might. This might just be a quirk of mine, a kind of strange-ism, unique-ism, that Americans love so much. A quirk that now only Ruth knew, a quirk that made us and, so, her, special. In spite of myself, I felt a sort of warmth spread through the hollow beneath my ribs. Her laugh was full of a self-satisfied pleasure that pleased me too.

Can I come with you?

I emptied the dustpan into the bin. I looked up through the windows in the slanted ceilings, it was already dark, which meant that the fox would likely be in the far corridor in the quad next to the chapel, maybe waiting, maybe not. I fingered the packet of yakgwa in my pocket.

Alright.

The fox was waiting where I expected her to be. She seemed unsurprised, but disapproving to see Ruth with me. The hot flash of shame that invaded my body was interrupted by Ruth’s incredulity.

I thought this was kind of like a metaphor or something? You’re telling me that this is usually here? Right in the quad?

I nodded silently. Reaching my hand into my pocket, I nervously extracted a round coin of yakgwa. A peace offering. The fox did not come and take it as she normally would.

What’s wrong with you?

I had muttered, but Ruth heard me nonetheless. She laughed her tinkly laugh.

You’re more naive than I would have imagined, talking to foxes, bringing sweets.

I shook the coin vindictively in the fox’s face, but she just blinked mutely, as if she were just a wild animal, and I just a human.

It probably doesn’t want that anyway, you know. Wouldn’t it want chicken or like . . . a dead squirrel, or that sort of thing? It’s a fox, you know.

In a single movement, the yakgwa was removed from my hand and moved into Ruth’s mouth. She moved over the flavor with rhythmic surprise. The sikgam, the mouth feeling. I watched, as her teeth and tongue got caught in the tacky texture of the coin—she no doubt had assumed it was just a biscuit or cookie. Watching her chew the thing, suddenly then rhythmically, mouth working over the flesh of the pastry, annoyance seared white-hot through my insides.

That’s good—what is tha—

I reached out a hand to her, as if to reclaim the stolen yakgwa, but then all I was doing was holding her warm face, cheek distorted as she ate the thing. We hung there in space for a moment. Her expression, again, was an intruder. The flickering of her gaze stayed by the force of my palm. She yelped.

What’s wrong with you?

That was for the fox.

Don’t you have another?

It’s rude. She’s older than us. She should have gotten the first piece.

What are you talking about? It’s a fox.

Ruth laughed, in a stilted way. Then the fox-unnie was gone, and I was left alone with Ruth, flashes of warm and cold, ran through my body, they were pressing a pulsing ache into the spaces between my ribs.

*

After that day, Ruth didn’t press her palms into mine on Sundays anymore. When she sang, I could see, in the frosty spring air, still, the vapor of her breath dissipating into the air. I hung onto that vision, resentfully, until finally May came and I could no longer even see that.

In my free time, I sat with the fox-unnie instead. Unlike Ruth, steady patron saint of blue jolly ranchers and that green apple shampoo scent, the things my fox-unnie liked were never consistent. In fits she grew tired of myulchi and muktae, refusing my gifting practice some days and then charitably receiving on others. The only thing she always accepted was the yakgwa.

언니 안에있는 사람들은 전부다 약과 좋아했나봐. Big sister, all those people inside of you must have liked yakgwa.

I would joke, and her lip would curl curiously over her canines in a grotesque smile. Perhaps it should have bothered me, the idea that somewhere in the bloodstream of the fox-unnie might be the finely-ground dust of many livers of many people, but it didn’t. The words came easy, the smile pleased me.

*

On a night misty like the first, I stepped out of the chapel and I saw Ruth standing in the corridor where the fox and I met on Sunday evenings. She and I hadn’t spoken outside of the chapel since March.

Ruth looked up at me and opened her mouth, but I crouched to the floor as if I didn’t care whether she was there or not, I had my fox-unnie anyway. The fox didn’t usually speak when others were around. I felt Ruth crouch down next to me. All three of us were eye level now. I could tell the fox was irritated with me. She spoke finally.

I’m sorry.

For what?

I knew, and she knew. I reached out a hand to touch the fox’s face and Ruth slapped my hand away with a vitriol and a force I had not seen from her. Her face, I noted with some surprise, was contorted in a way I had not seen before, her lush eyelashes starkly framing a burning disgust in her eyes.

Don’t touch that. It’s a wild animal.

She wasn’t though. I didn’t know how to explain, exactly. The fox, like me, ate yakgwa from my hand and sat quietly in corners and observed them, deigning to touch them. Did that make me, too, a wild animal? In the limelight of Ruth’s keen, burning gaze, though I felt I had to explain.

And, at once, all of our conversations seemed imaginary too—maybe I had hallucinated all of it.

She’s like me, though. Don’t you think?

In the air, I traced the curve of the fox’s long nose, high and regal, and her sharp eyes, deep and black. Ruth did not answer my question.

Am I like a wild animal?

Ruth seemed very agitated suddenly.

No. Well. Well, that’s not the point. Esther, that’s a—a creature. You really shouldn’t be out here all the time like this. What if it bit you and you, got a disease or, like, rabies or something? I know it must be hard being away from home and everything, but . . .

Ah, so Ruth knew how often I was here. Creature. I turned the word’s mouthfeeling—sikgam—over with my tongue. In a sudden motion, I moved away from the fox and flopped onto the grass on my back and stared up at the sky. The stars were mostly obscured by the lamps above us, whose light was smeared across the black. I felt, by ripples in the grass, Ruth hesitating for a moment and then lie down beside me, pressing her hip to my own, in half-apology. My body again tingled with pleasure and shame, which focalized into a single, burning point in my palm as Ruth pressed hers into mine, once more, clammy with dew and with something else.

I missed you.

The words came out of me slowly and then all of a sudden; I was coughing up a ball of spit and fur that had been stuck in my throat for months. This is how it was meant to be: non-strangers touching non-strangers, and words in the air for the other to taste.

Ruth rolled over onto her side and looked at me, and she smiled so that her eyelashes kissed the tops of her high cheekbones. Curling into each other, we made a crude circle with our bodies, shins, foreheads touching. The fox was gone, I knew, with a tinge of sadness.

*

The next time I saw the fox was when the orchard was sold. Halmeoni died on a sublime July day during the monsoon. The rain came down in sheets that day, like the craggy mountains had pierced the membrane of the sky, letting down walls of water all at once. Umma called me and informed me on a Sunday morning, three days afterwards, funeral having been processed, ashes having been scattered, farm having been taken care of. All settled and squared, our last ties severed to that decaying city. All dust, all dust. The abandoned Jecheon mines and halmeoni’s bones in the Eastern sea and the dusty rot of Korean pine planks of the old home.

I skipped service for the first time. Ruth’s soaring notes would cover the absence of my alto ones, in any case.

Though I hadn’t seen her in weeks, the fox was in her corridor when I went to find her, as if we had arranged to meet in advance. I lay on the grass and she curled into my side. I could feel the blood beating through her small, warm, solid body. It was the closest she had ever come to me. I didn’t cry, only slept, had no dreams. Like that, days passed, then weeks. Each dusk, I’d crawl into the little unkempt, weedy space between the corridor and the green lawn of the quad, and fall asleep in the balmy summer air. On particularly warm nights, I’d imagine that the warmth from the ground and from the fox-unnie was actually the warmth from the ondol floors of the house in Jecheon, and the warmth from halmeoni emanating into me as we pressed our backs into the earth and felt sleep descend on us like a weighty veil. Like that, I’d drift off to a clear, clarifying sleep, next to the fox. I missed service week after week. Occasionally I’d wonder who’d clear the pews and sweep the dust away; mostly it never crossed my mind.

At some point, I was awoken by the ringing of a footstep. When Ruth came into view through the corridor, the words muscled their way through my throat before I could catch them.

가—가! Go—go!

I shooed the fox-unnie away. The second betrayal. I regretted it almost instantly, but then it was too late and the fox was gone and Ruth was suddenly above me.

Wordlessly, Ruth pulled me off the ground. We were moving then, towards the chapel, glimmering dimly in the distance, like a fake-place, a fabrication of this school, a mirage house of Ruth and Esther. I was sat in front of the chaplain in her office, a fluorescent, pathetic interrogation room for the sick, sinful, crazy. I wondered which of the categories I fell into. I felt Ruth’s gaze on the back of my neck like a frantic touch. The chaplain broke the silence.

Esther, is everything okay? Ruth has—we’ve—noticed your absence in service these past few weeks.

I sat mutely. I guessed this was, in its way, Ruth’s gift to me.

Esther, we can’t help you if you don’t let us. Ruth also mentioned a concerning obsession with the wild animals that come in from the forest—that can be quite dangerous even if you were in a . . . good . . . mental space . . .

Animal.

What?

Just one animal. She’s a fox.

The chaplain looked startled, and that look—concern? disgust?—flickered across Ruth’s face once more. That look. 젠장. Damn it.

You know, a lot of students have a hard time adjusting when they first get here. But, you have a lot of resources here at your disposal. Really, there are lots of folks you can speak to—

She talks to me.

Why had I said that? Suddenly, I guess, I was angry. Maybe because the fox talked in Korean, no one else could understand it, but that wasn’t her fault. There was no doubt in my mind that the fox spoke. I could not particularly ever remember how the fox spoke, did it move its snout up and down? Or perhaps contort its canine teeth around the round syllables of our language. The phenomenon escaped me. Nevertheless, I was certain it must be true.

What?

The chaplain was looking at me in a very strange way. Not taking her eyes off of me, she pulled out a pad from her desk and began writing—I laughed. It was just as if I were a character in an American drama who had gone a bit wild, a character me and my grandmother might have vaguely seen on the television during foreign broadcast hours. Ruth’s hand reached out and touched my thigh—and I felt the warmth of her hand elicit hot rage rather than sudden desire. The laugh morphed into a cruel silence. My insides were twisted around a spot under my ribs, these people.

남을 함부로 만지는거 아니잖아! Don’t touch those you don’t know!

She talks back.

Esther . . . Though I’m sure you feel that way, is there something else going on that might—

The chaplain’s hands were pawing at my shoulder. I felt the weight of her arm and the weight of sympathy heavy. She was suffocating the life out of me. I had made a mistake.

I stood up from my chair.

I have to go. I’m sorry.

Where was she? I heard Ruth and the chaplain vaguely calling after me as I raced outside. I didn’t have any more yakgwa left to apologize with, to barter with, in the case she really was just a fox, a strange, Korean fox who liked yakgwa more than myulchi and myulchi more than muktae. I was running, and I think it was late. The night felt balmy and heavy in a frustrated, August-fashion. No mountains here to pierce the sky, to wash away halmeoni and her apples.

I ran through the corridor and turned left sharply, wildly, then right. The fox was not here. I had betrayed her too many times.

언니! 언니. Unnie! Unnie.

Sobs crescendoed in my throat. It was a monsoon of sobs, well timed to the season. Maybe the first in a full year. They overwhelmed me. I could not feel my feet stumbling forward or even the tears on my face, only a cracking, breaking pain in the space beneath my ribs and a horrible, thick feeling in the back of my throat. I ran across the quad to the edge of the campus where the road separated our manicured lawns from the forest that always threatened to remind us that our encampment was an unnatural one.

I saw the fox, an apparition across the highway. I was crying now, something had pierced the membrane of my eyelids, and the tears flowed like sheets of water over me. I was drenched all over in the sheets of water that came through gashes in the Korean sky rather than damp in the vague mist that hung over the August of New England.

언니 내가 잘못했어. 내가 잘못했잖아. 미안해, 용서해줘—Unnie I was wrong. I swear it, I was wrong. I’m sorry. Forgive me.

The fox looked at me mutely, as if she were just a wild animal, and I were just a human. I could feel the pain in the hollow beneath my ribs continue to crescendo, to twist my entire body inside out. I ran towards her. I wanted to touch her.

I heard Ruth scream behind me, then a great crumpling, and then nothing.

*

있잖아. 어쩌면 그게 사실이였을지도 모른다. You know. It might have been true.

알아줘서 고맙네. Thank you, for knowing.

The girl lay in the middle of the road, illuminated in the dim light of the streetlamps. Thick blood covered portions of her flat, round face, but a patchwork of skin glowed through under the white light above. Her skin looked even more porcelain than usual, no evidence of emotion simmering under the surface of her peach fuzz. No scent hovering at her wrist and neck points when her blood ran quickly with thick smells of shame and desire. Thin ribbons of that blood twisted from her temples now, pooling on the ground, never again to rush so close to the surface of her skin as the fox lay in her lap. Make no mistake, the fox was quite sad about it all.

Nevertheless, the fox knew the girl wouldn’t mind having her liver taken that night. It really was a shame, though.

그는 언니라 부르던 애가 겨우 애였는데. She was just a child, child who had called her unnie.

The other girl ran off to get others, the driver of the car was turned away, face only illuminated in the blue light of a cell phone to ear. For just a moment, that moment, the dark road was frozen in time in the slow, red light of the car brakes.

The girl’s stomach was like warm butter, as if she were assisting me. I made quick work of the extraction. Against my teeth, the girl’s flesh gave way, almost with pleasure, as if to say, I understand, and, it’s alright. Her blood was sweet, the liver soft. Then, I had my prize and made for the forest. I would not return to the campus for at least a long time forward.

*

I watch from the other side of the highway as the others gather round. A gaggle of people clucking. Face is mostly obscured with thick blood, soft ceramic of stomach sliced cleanly open to the night air. If only, if only, they were saying. If only they had noticed her sooner, if only she’d had someone to talk to, if only she could have adjusted better.

A mirage of my mother appears in my mind’s eye. Arms crossed and with a still grief on her face. In the commotion, she is quiet. All dust, all dust.

I see Ruth wailing louder at the sight of the stomach wound. She swears it was that vicious, mangy, horrible animal. 오열, 오열, sorrow, sorrow, into the shoulders of those nearest to her, spitting grief like stones into the still water.

I knew that the child would be happy to be with me, though.

아가야, 니가 잘못한거 없다. Child, you did no wrong.