“I believe we had a reservation for this one,” they called out, not unkindly we must admit.

Oh, they had reservations? So did we! We had been playing these courts for twenty, thirty years. Who were they? Who were they with their dark, hardly gray hair, their square glasses, their digital watches and mathematical meekness?

“We’re finishing up,” we said. It was but four minutes past the hour.

They had wool sneakers (not what we wore when we were their age), they had facial stubble (we shaved every day), they had ear buds in their ears, not unlike our hearing aids which helped us when we chose to wear them (rarely did we choose to wear them).

They looked like our children, but they were not our children. Our children were far away.

“The calendar is right on the app,” they said, “You can see our names there.” The app! The app! What app? We talked to the pudgy girl at the front desk when we wanted to play. What app?

“Alright,” we said, jovial, for we were in charge. We packed up our balls into our leather bags. We sipped from our plastic water bottles (theirs were metal, we could see in their eyes the fear for the Earth, the future that they would confront, long after we were gone).

“You new to the club?”

They nodded.

“Been playing tennis long?”

They nodded.

We let the taciturn have their court and stood at the side to watch their game—they moved quickly. They were not just rallying like we did but playing properly, calling out scores in proud, loud tones.

We had once moved like they did, still could, sometimes, when the weather was right.

In pockets they had their cell phones (ours were in our lockers, or else at home). They took photos from the court. They smiled with big white teeth and we wondered: who were they to smile?

But we didn’t like tennis much anyway. No, the club facilities proved this. Tennis was in the back, in the worst part of the property, hidden away with just three courts, two that had shade. In our beautiful private club we preferred golf. That was our game.

Try navigating our fields, we said. We saw them sometimes at the driving range, hitting not quite badly, but out in the real thick of things, across our two courses of eighteen holes each, rarely could they find the time to play an entire game. This was for us; we knew the bumps and divots. We knew how to hide some balls from each other in our pant legs or in the side of the cart so that we could place it right where we wanted it to be; this was part of the game, we reasoned.

We’d find them in the club after for lunch. They wore no jackets (did we have a rule? No? There was no rule?) We had soup before salad before sandwiches while they ate quickly. Low carb, no carb, gluten free. What they ate seemed like food for lab animals, sometimes they chugged brown slush in a glass, liquid for lunch. We didn’t even know the club served such food.

They chatted with our waitresses and made them laugh—certainly we too could make them laugh. What were they saying to our waitresses?

“I don’t suppose you could do this without the bread? No, no, it’s just—that stuff can kill you! Are you taking probiotics, sweetheart? There was this podcast that came out the other day . . . oh you do? Please do send a link.”

Where had they come from, these men? Not from us. Our children were not these men. Our children were not here, they were living in the big cities, they were learning painting or dancing in clubs or asking us to seed them opening a restaurant. No, these men were white and brown and Chinese and sometimes even something else. They talked about writing code. What we called computers they called machines. They knew calculus—who knew calculus? Maybe Roger Falstone, who never came around anymore anyway.

They were serious men but they were also so silly, like big children in their T-shirts and joggers.

We did try to talk to them, sometimes over the urinals or in the vestibules where the payphones used to be, while we waited for a lunch table.

Business seemed approachable but no, we could not talk business. They had no sense of our austerity. We had run the world from our corner offices and executive washrooms, but these men did not even go to the office. We’d find them working in the lobby of the club. We asked what they did and they gave us vague answers—advising, consulting, steering. They said they were angels or that they were making platforms. We did not even pretend to understand. They did not cite their parents, as we did, still did, even after our parents were gone. But yes, they did have money.

We tried to talk about movies or shows but these men did not watch those things. They did not go to the theater. They did not own a television (we wondered why they sounded so proud of this . . . as if they weren’t always tap tapping on their phones around us).

We could not even talk travel, for when we tried, they described visiting places that did not interest us in the least: Thailand, Sri Lanka, Nepal. These were places that to us seemed dangerous, dirty, the places we purposefully avoided as we built this club and stayed in those fine lovely resorts in Hawaii, our Mediterranean cruise ships, our Breakers, our Newports, our Monte Carlos.

And love? No, we stopped talking about love. We each had our wives, or were shamefully divorced, but they, at the slightest provocation, told us everything. They were polyamorous, their wives had girlfriends, they had experimented with each other—no, we looked at our shoes but they kept talking—they had clubs in the city where they’d dangle from the ceiling, they had toys they inserted into their bottoms, they were spanked and cuckolded and described complex rituals of consent. Perhaps we had tried somethings in our days, we had had our adventures, but not like this. We excused ourselves to lunch and to an early bedtime.

Then, soon, they found the courses. We had long ago forgotten about the idea of improvement, that the hours they spent on the driving range could change their skills, but here they were now, tapping their toes at us again, speeding us along our leisurely eighteen holes. We looked up at them and saw their hog ties, their butt plugs, their confusing set of girls and women, we couldn’t meet them in the eyes!

The card rooms were safe, yes, we liked those. Dark and cool, below the dining room. They served butterscotch cookies and hot tea all day. We played bridge for hours and got changed for it like it was a sport.

But there too, they found us, like our kids once did when we were in our studies with cigars way back when . . . a curious face tugging at our pant legs.

Here there was something else, another dimension. Perhaps we did not have the tendon strength, the vision for swinging, the physical agility for tennis or for golf (no one dared say this out loud), but bridge was not like those things. Here we still had the instinct, the skill, the careful, years-deep relationships of looking across the table into another human’s eyes to read their intentions, to play the cards they silently needed you to play . . . We did this well, no dullness.

Rex Myerson was the king of this, the king of the card room even before the invaders. He was our straw-haired bridge master (his hair was so light but not gray, just white and yellow hair on a tall stringy body). Rex was never on the golf course, probably didn’t even own a tennis racket (we had seen him trip on his shoelaces taking a jog), and in the lunch room he stuttered when talking to the waitresses . . . he could hardly even order a turkey sandwich. We had driven him to nights at the theater where, on the ride back, he talked endlessly about the quality of the costuming, the musicians’ skills, the interpretation of the script . . . we were so bored! Sometimes we saw him crying by himself in the locker room. We rolled our eyes. Crying over what, Rex?

But in the card room Rex was prime. We fought each other to be Rex’s partner. When the game was so silent, and the stakes were high (a few bucks, nothing big, but we couldn’t cheat here as well as we could on the golf course), Rex would do us good.

Yes yes, we trounced them in the card room. We could not be beat! They barely knew the rules of the game, but even when they learned, when they had the terminology down, there was something about the eye contact, the need for collaboration. They just could not make it work. They could tap tap on their keyboards and command their machines so well, but the economics of trade, of strategy, of face-to-face human communication escaped them. We trounced them good.

Here we wondered: what trick would they pull to do better? How would they come back to unseat us here, this generation of little princes?

No, they could not. They went back to golf and tennis. They took their phone calls out front. They got into their cars, which hummed like beetles.

Rex did not notice what a triumph we had accomplished, or if he did, he didn’t mention it. He loved his game, he loved that we were more enthusiastic to join him in the card room. We were happy to see him happy; after all, he was one of us.

Still, we would prefer not to dine with him. Good then, we said, that he was staying late in the card room each morning and afternoon, albeit, with one of them. That husky woman, bifocals around her neck (our wives had those bifocals). We asked our children to search her name, Daisy Singh: she had built some great chip factory in Malaysia with profits that made us salivate. She had lost as many bridge games as any of them, but only she had turned to us (Rex, in particular) and asked: how do you do what you do?

Did we care that there was a woman in our card room? No! We were good, progressive men, raised by the children of the suffragettes. We cared that she had her cell phone, that she was a tap tapper, that Daisy Singh, but if she canceled out lunch with Rex, perhaps that could be good.

Yes, we took our defense of the card room in stride. We had learned to live amongst these aliens, we realized how smart we always were, how better adjusted to the world. We reveled in what scared them: our elbows and happy touching, our willingness for nudity in the locker room (why did this, of all things, bring them shame?), our American patriotism and our love of red meat, blue skies, our own white buttocks.

Fourth Of July seemed then a victory lap. We pushed the club planning committee big time on the barbeque. We wanted more racks of ribs, a flag even bigger than last year’s, a country band to fly in to play for us (on the phone our children warned us of the band’s reputation, politically disgusting, we didn’t care!). Our victory was hot dogs, processed meats, the things we had in our childhood, not theirs.

We would have the place to ourselves. We would drink whiskey, smell mesquite, be amongst our own. Us in our suits and stars-and-stripes pocket squares, our wives dressed to the nines, everyone together at a long and welcome table.

So then, we didn’t even mind Daisy Singh at the buffet, a single woman, a big rack of ribs on her plate. Rex waved her over—what was that man doing? There was an empty seat on one side of him, the other side being his gin-drunk wife (Rex Myerson’s wife, the seamstress was how we thought of her. She mended tears in our coats and in our wives’ dresses. All of us had little stitches up and down our lining from Valerie Myerson’s fingers. Today, the woman had tailor’s pins left carelessly in her lapel that Rex did not notice, nor the liquored smell of her breath—of course, we did. Our wives even more so).

We were meat full. We were drunk. We let the woman sit with us at our large table.

“Tell us,” our wives said (here, now, our wives were with us. Never had we betrayed them in any way, never had we ever behaved in a dishonoring way to our marriages).

“Tell us, Miss Singh,” we said, “How are you finding our club?”

“It’s very sweet,” she said, a napkin catching sauce over her large chest. Her blouse had flowers in purple and gold, certainly not the colors of the day. “The greenery is so lush.”

“Yes, yes, we are proud of our landscapers.”

“I was walking through the foliage the other day—”

“The foliage? Walking?”

“Yes, there’s a beautiful area over there—” Daisy Singh pointed, towards where? The golf course?’

“By hole seven?”

“Yes I believe it is around there. You know what I found? Wild spring onion.”

“Onions on our course? Yes, we suppose it’s possible.”

“I’m wondering,” she said, leaning forward, “What else could grow here. I’d be interested in seeing—imagine it, between the onions, those ducks by the lake, if we had carrots we could even make an entire meal.”

Our wives fed those ducks. We saw the stale bread ends they saved in the pantry for far too many days. No, no, no.

“What an interesting idea!” Rex said and we shot him the angriest stares we could muster. Can’t you see, man, can’t you see!

After that, our wives took up the fervor more than we had. They hated the new crowd. They walked in tight groups and shouldered past them in the hallway. They stopped waving at them when they drove past someone walking (like the person even noticed this). But we loved them. They were on our side.

They begged us to do something, but what could we do? We dared not share the humiliation of the tennis courts, our shameful retreat from the golf courses, even as we told them stories of the card room like we had returned from battle.

What could we do? We decided to ask Roger Falstone about it. He lived up on the hill in the house his grandfather built when he founded the club. We didn’t like to drive up there, it made us sick, the way the cars would rock on the pathway. But we had to, so we got into three or four cars (Rex asked to come. We worried he would sabotage, or else just otherwise spoil the fun, but oh no, he pleaded, he begged. We let him in but he had to sit in the very back).

Roger had a suit of armor at his door and antique hunting rifles lined along each wall (loaded, he told us, just for fun—they were hard to aim and fire). He had an ancient stock ticker in the center of his library that he somehow managed to connect up so that it kept printing real numbers, real information. It was always too loud; now, thankfully, markets were closed. Roger treated us, all of us, to cigars. We looked at Rex, like he might tattle to the wives.

We asked Roger: Had he been to the club lately? We explained about the men in joggers and ear buds, the tap tappers, the talk we heard of computers. We had understood things during the dotcom times, but this we didn’t.

“Computers might not be the right word for this,” ancient Roger said, “But go on.”

We told him about the liquids they drank instead of eating. Their smiles and their optimism. We couldn’t find it in us to mention their sexual proclivities, we squirmed in our seats, but we told all the rest.

“But, despite this, they have so much money! The real deal.”

Roget smoked his cigar. He ashed it in a great, green ashtray. He stood up and looked down out the grand library window. We peered to see what he could see. It was everything, a great view from up on this hill.

“Give it time,” he said, “Time is everything. These things do not go up and up. They change. You know this. You have all been at the top and at the bottom. These men, they don’t yet know what it is like when it stops raining, when the drought comes. Watch and you will see.”

Yes, we descended the hill that day with much on our minds. Rex couldn’t take the rocking of the car. He kept asking to pull over—which we did, mercifully, to let him out to vomit on the side of the hill.

And Roger was right. A few months later, we saw it on our televisions and in our newspapers. Crash! All those confusing names we heard muttered about in our club—semi propellers, crypto bazookas, bit smashers—were there! Things were not looking good, money was drying up. There, we recognized, was Roger’s drought.

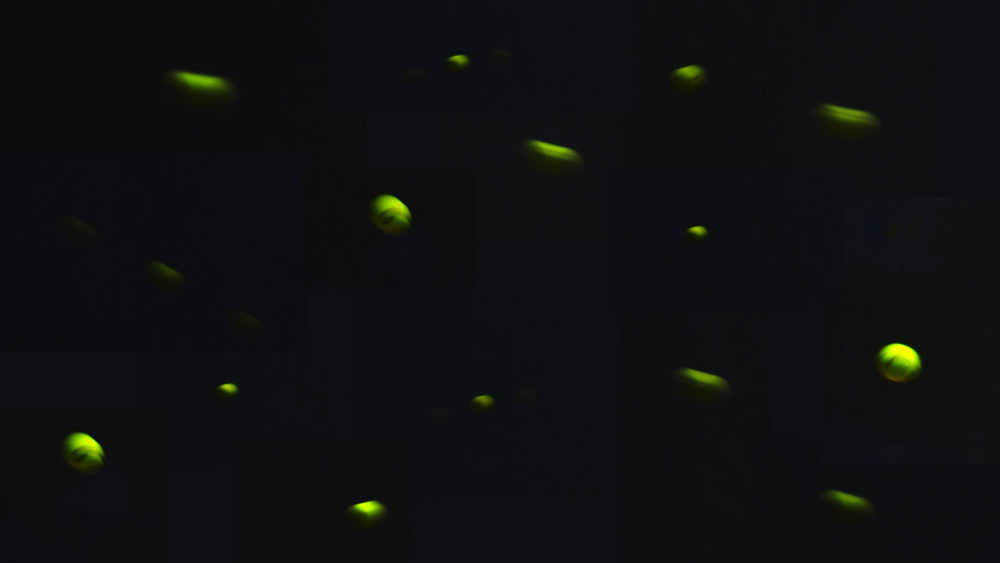

We returned to the club to find they had scattered. Our card rooms were empty, not even Daisy Singh was there (Rex lingered long, was late to lunch when all the good slices of turkey were taken). We found tee times were back and available and we gobbled them up as we once had. We took our precious time on every hole. We didn’t even hide extra balls in our pockets, the play was so sweet. And slowly, some of us found our way back to the tennis courts. We paid to have our rackets restrung, we popped open fresh cans of balls like champagne. We gave each other six tries on each serve.

Later, we heard gossip (from who? It was unclear. Not Rex who, even though he went to tea weekly at the museum café with Daisy Singh, told us nothing of what they talked about) that many of them had had to pull their daughters and sons from the private school nearby. Home schooling? (we laughed), or else, the public school . . . we considered all those young bodies, their futures upended. We didn’t like it, though in a way we did like it, but we were also concerned. We thought about that aspect more than we thought about just about anything.

But then something else came along. Roger Falstone descended one day into our dining room with who on his arm but some terribly young new wife. That got our attention. That became our discussion. How brazen, how insane, how limber she looked. We told our wives we were as disgusted as they were, but then in the locker room, we talked differently. Should we . . .? No . . . Unless . . . To us, this was a fascinatingly interesting line of questioning.

Somewhere amongst all this we attended the funeral of Rex’s wife Valerie; he never told us how she went (we suspected it was her liver). We wore our black suits and we patted Rex on the back. We withheld our usual jokes. We sat up so straight in the pews at the temple for we could not risk a stitch popping.

Who would we turn to for mending?

The rest happened like that, the way a loose thread emerges and quickly. Out of nowhere, soon a hole is there and then the entire coat seems to have disintegrated back into its raw material. Not a year after Roger appeared with the young beauty did he die. The woman took the money, sold the house on the hill, that suit of armor and the guns and the stock ticker. The club went to a vague overseas owner, someone or some thing we never met; it was hard to tell what changed. Some of us found our way into the grave as well; our hearts, our lungs, our old sports injuries.

Daisy Singh appeared again, on Rex’s arm, though we seemed unable to pay that much attention. We were struggling to fill a golf game between hospital visits, medical checkups, goodbyes that were getting duller and duller.

We found ourselves, somehow, in Daisy Singh’s home (Rex’s home it was, though we never ever visited when it was Rex and Valerie). She made us tea. She made us dinners. She lent us paperbacks, which we read in doctors’ waiting rooms; we liked them, we gave them back to her with a sincere thank you.

In the end, we were dying. We were dying when the men came back to the club, a bit more worn for wear, a bit wiser, a bit more like us. Their daughters and sons were in good colleges, we heard, yes, back on track. We liked to hear this. We liked to hear this in the few moments when we managed a visit back to the club, struggling to enter the dining room, struggling to rise from its chairs. They helped us. They picked up our fallen napkins, just as we had done a long time ago, for others, hadn’t we?