Several years ago, while I was working on a project on memory with a group of young Somali refugees who were attending the Asinitas Italian school in Rome, I received a proposal to participate in the “Dizionario”—dictionary—section of the program Fahrenheit on Rai Radio 3. Every week an author was asked to choose a different word for five days in a row, following their own personal criteria with maximum freedom. Since at school it often happened that we would discuss the difficulty of translating words and concepts between Somali and Italian, the proposal from Fahrenheit seemed to me rich with possibility. I presented the project to the students and their teachers, and they welcomed it enthusiastically. Our meetings were pretty informal; every discussion was generated by a word and, in some way, by the impossibility of translating it. We would find terms that came close to the word, but that also brought us to unexpected places.

One of the words discussed was the verb partire in Italian—to leave. Listening to the students’ stories of the moment they made the decision to leave was very emotional. It was something that they continued to think about during the following years, like an obsession. They called this obsession buufis in Somali, from the verb buuf, which means to swell, to burst. Hardly anyone spoke of a single reason. Deciding to separate yourself from your home is very difficult; it’s like a defeat. The people who find themselves in this condition are almost possessed, persecuted by spirits. Leaving is often something sudden.

In Somali there is a very well-known lullaby that a woman in our group would sing: Hobey hobeeyaa / Yah hobey hobeyaa. The lyrics of the lullaby had a word that fascinated me: carrabay, which means to leave in the afternoon. You leave in the afternoon only in the case of grave calamities, when you are forced to, because leaving in the afternoon, in the middle of the day, means leaving many things incomplete.

One of the young men who frequented the Italian course was named Farhaan. His story was probably the one that struck us the most because of his repeated departures, his pilgrimages from one town to another, first towards Yemen, then towards South Africa, and finally towards Italy. In between these destinations he would always return home. It was as if his leaving was always born from the desire to return. The first time he leaves in the afternoon. He is only fifteen years old and he leaves Beledweyne, his city, to save himself from the armed clashes. He runs, runs for sixty kilometers, he tells me. He runs for twenty-three hours straight, just short of an entire day. He remains in suspense. A few days later the war reaches even that city where he had taken refuge. To save himself he dives into the river and swims to the other side. Some people follow him, but they don’t make it and remain trapped in the river.

The big reason why they leave is mentioned only sporadically, as if it were a curse: it’s the civil war, dalgalka sokeeye in Somali. The writer Nuruddin Farah in his novel Links explains the significance of the expression in this way: “Dagaalka sokeeye [ . . . ] "In his mind, Jeebleh couldn’t decide how to render the Somali expression in English: in the end preferring the notion ‘killing an intimate’ to ‘warring against an intimate’.”

This idea of intrinsic intimacy in violence is very interesting. Maybe it’s also the reason for the shame, the reason why people rarely use that expression.

They wouldn’t say civil war, but burbur, which means falling apart. While I was in the middle of that falling apart, I decided to take on the trip.

This is what happens when disaster reveals the limits of language. As the South African writer Gillian Slovo says: “Language is inadequate to represent experiences so horrendous that they seem to challenge any possible comprehension.” Is language able to reconstruct a word split by violence? One of the major challenges that writers have to face is that of sharing traumatic experiences. As James Dawes writes in his book That the World May Know: Bearing Witness to Atrocity, there exists a contradiction “between our impulse to heed trauma’s cry for representation and our instinct to protect it from representation–from invasive staring, simplification, dissection.”

When I left my house in Mogadishu in January 1991, my son had been born just a few days before. I laid him on a pillow, and I wrapped myself in a large black veil. For the moment I thought that we would never return again, so I grabbed my latest diary, one of the notebooks in which I had written with much devotion for innumerable years. A few hours later, my house was taken under assault and sacked. Pillow, veil, and diary: these objects were the symbols of that escape, of that split between life before and after the conflict, the talismans of a writing habit that was then interrupted for many years—seven—until my trip (maybe the most important one of my life) to Zeist, in the province of Utrecht, in the Netherlands.

It all seemed extraordinary. I hadn’t been on an airplane in such a long time. The flight was scheduled for the early morning. I think it was March or April because my son, who in the meantime had turned seven years old, wasn’t going to school because of the Easter holidays. I got dressed, I dressed my sleeping son, and finally I put on my contact lenses. I was anxious and in a rush, so I accidentally dropped the left contact, and I wasn’t able to find it. At that point I could have easily put on my glasses, or at least shoved them into my pocket in order to be able to use them when I would truly need them, but for some strange reason (maybe just vanity) I decided instead to leave the house wearing just one contact lens. My first experience with the diaspora was born out of this altered perception: sharp and clear on one side, confused on the other.

Nearsightedness is a veil between the person seeing and the external word. The veil casts a shadow over your gaze, but at the same time the naked eye is able to pick up on the smallest details, when they are close. The French feminist writer and philosopher Hélène Cixous, in her essay Veils, describes the experience of closeness and distance in this way: “Not seeing is a defect, misery, thirst, but not seeing oneself is virginity, strength, independence. Not seeing, she couldn’t see herself being seen, that’s what gave lightness to her blindness, a great freedom of abnegation. She had never been thrown into the war of faces, she lived suspended without images, where large indistinct clouds rolled around.”

In what way do individuals who have lost all their points of reference recreate their roots, restart a new life? Do time and distance allow us to better understand how the past influences the present? I can say that my trip to Zeist was like a return home, to my traveling home. It was then that I was able to reacquire my ability to write. I chose the diaspora as the ground for my writing, and the characters of the diaspora have inside of themselves this brokenness, a link between the before and the after, a frontier that contains something very precious: a secret, a detail, a root. Maybe for this reason the last word that the Asinitas students and I chose was home.

The Doll

I don’t have my childhood toys anymore. And yet Mom calls me on the phone and tells me that she found the doll. I don’t remember it and so my mom immediately takes a photo of it to refresh my memory. The doll is all nice and comfortable in its Veronese living room and is wearing, for the occasion, a crocheted pink dress.

And, given the guilt of my forgetfulness, my mother rebaptizes it with a new name, Gigia, her own nickname that still today my mom’s childhood friends call her by, the same ones who would write her long letters, when she was still a girl and had left for Africa, together with me as a child.

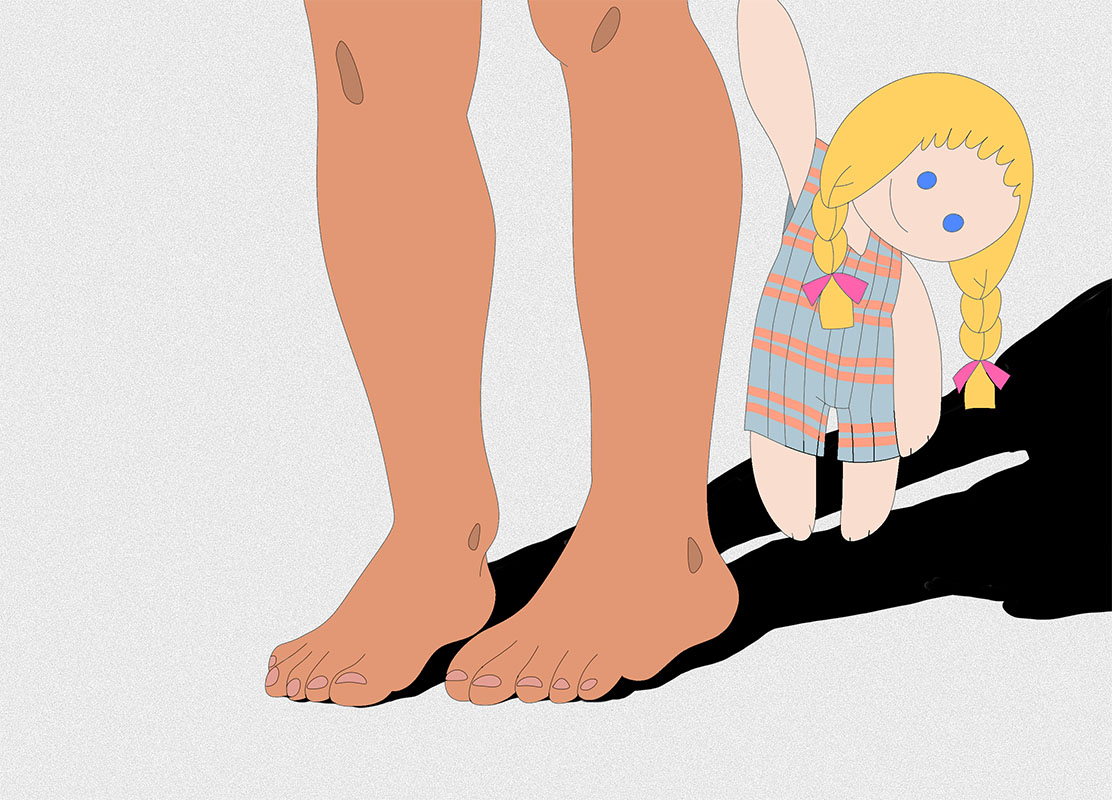

What I actually remember well is my childhood bedroom in Mogadishu and the large ragdoll with yellow roped hair and long Turkish-style plaid overalls.

It would just hang there in front of my bed and watch me with its big light blue gaze, immobile between two lobsters. In those times, a lobster glued to a showy Formica fifties-style table was a quite common souvenir in Somalia.

The ragdoll’s name was Casimiro and it was a friend of my mother’s who gifted it to me when we left from Verona to definitively go live with my dad. For me a doll and for my mom a book about reincarnation. It’s funny if I think about it: Casimiro was like a good wish for the trip, the lobsters were like a welcome.

My mother quickly invented a story about my nocturnal friend, a fairy tale in which there were no lobsters, but just Casimiro, who wanted to fly. First she built two wings out of wax feathers and would jump off the small roof of the house. By the end she opted for the safer and more technological helicopter. The story was recorded on a cassette so that I could listen and relisten to it every time that I felt the need to. In the meantime, there was another guest who was trying to claim a place in my room. It was a little mason wasp that I never got tired of watching, in and out of the window, as it built its house comb by comb.

Some nights I imagined my ragdoll coming to life and following the mason wasp around the new city, together with me and the two lobsters.

To my great disappointment, my young aunt Xamsa took the initiative to strike down the wasp nest with a broom handle. We couldn’t let the insect finish his work unbothered, otherwise it would have ended up destroying our own house.

Casimiro remained in her place without blinking. However, cautiously, other characters began coming to life in my universe, like my little cousins’ clever jackal, or a treacherous hyena, or a female cannibal with amazing hearing.

After sunset, when darkness began to shroud everything, we would all gather on the carpet to listen to stories. It was always the grown-ups who started, short fairy tales and fables taken providentially right out of the everyday lives of the adults.

I never spoke a single word: my mother’s stories sounded too remote to me, impossible even for my cousins, with their hyperbolic imaginations, to comprehend.

Sometimes, when my cousins would get tired of telling stories or of chasing each other around playing hide and seek, I would show them my dolls. Taken aback, they observed my dolls and how their eyelids closed, the long eyelashes and the silky hair. Their pearly color was almost scary when illuminated by the scarce moonlight.

Then dinner would arrive, and we would cram ourselves around the single communal plate, take a piece of bread with the tips of our fingers, and then dip it in the stew.

I remember the evening when they told us that someone had stolen the dolls. It was my father who announced it, shocked that someone had broken into our house for such a futile haul.

Dhakac dhakac dhumjilikow dhaleeliyo dhuc dhuc, ka dhamdhamow dhashow bax

Finally my mom is coming to visit me in my new house. She can’t wait to open her suitcase and show me the doll. This time she’s dressed in orange, my favorite color.

“You seriously don’t remember Gigia?” She asks me. I let them both sit down on the couch.

“Gigia never went to Mogadishu,” I tell her, “all my dolls were left in Somalia to go to war.” She replies with a doubtful look.

“I didn’t grow up in the house in Verona where you found the doll,” I reiterate, “but in Mogadishu. Don’t you remember?”

“What about your first three years of life?” She asks me, disappointed.

That’s right, my first three years of life.

And yet Mom returned to her native city only after a long time. The Veronese house where she had grown up, emptied of her parents, had remained unchanged for a long time after the mourning, silverware and intact clothes, pictures and letters kept in drawers.

I imagine her as she rummages through her old abandoned home, and suddenly she becomes young again and forgets everything. The truth is that we don’t ever want to stop looking for the breadcrumb trail that we made in the woods to not lose our way.

Everything returns to the way it used to be: there is a little fireplace in the kitchen, the dark wooden floor, and Grandma makes the tagliatelle dough with nettles. Mom is a great worker, during the day she works as a secretary in a bakery and at night she studies to get her degree. I go to daycare, and Dad—who is a student and who still hasn’t returned to his country—takes me up to the bastions during the afternoons; one time we even went to the zoo. I would have forgotten about it had it not been for the picture of us giving peanuts to the elephants. Dad is slender and happy, a dreamy gaze in his eyes, a hand resting on the fence. “I’ve seen them free, elephants,” he tells me.

Soon he’ll return to his country, and when Mom finishes university, we’ll also take a plane to rejoin him in Somalia.

My grandmother takes care of me. She’s a tall and elegant woman who always wears heels, and when Dad returns to his country, she warns me not to stick my little fingers in the holes where she puts mice poison. At night she has terrible nightmares and is afraid that that white powder will kill me before I get to see Dad again. She’s always loved my father and when an imprudent barista kicked my parents—one of them white and the other black—out of a cafe, she slammed her fist on the table.

We are all around the table for dinner and since I’m not eating anything, Grandma asks me if I at least want to eat a little bit of my favorite cheese, Dad’s cheese, invernizzi stracchino. It’s wrapped in a thin white plastic, which has many outlines of faces colored in black on it; they almost seem like the heads of black men, and Grandma says it candidly: “Dad’s cheese, the little black men cheese.”

“Instead of that, come to the window and look at the snowflakes,” Mom exclaims. “We’ve never seen ones this big before!”

I’m a good child, and so Grandma takes my hand. It’s winter, the darkest day of the year, and we sing a well-wishing nursery rhyme to make candy rain down from the ceiling. Santa Lucia bella, dei bimbi sei una stella, nel mondo vai e vai e non ti stanchi mai.

In a few months Mom and I will also go around and around the world, to meet up with Dad in a country far away “and when you come back to visit me, you’ll be tall enough to ring the doorbell and you’ll be holding a little brown boy by the hand, as beautiful as you!” Who knows who this little brown boy is in my lovely grandmother’s fantasy: a little boyfriend, a little cousin, or a little baby brother?

To this day, I still sometimes think about that thin plastic wrapped around the stracchino: a white container on which my faraway Dad’s head was replicated infinite times.

“Do you think you have moretti to clean up after you?” My mother has been impatient since she’s been pregnant with my little brother; she’s had a difficult pregnancy. She loudly smacks her lips and complains about the messiness in my room. We have to pack, we’ll be leaving for Italy soon. Is it really so difficult for me to give her a hand? “Do you think you have moretti?”—little black slaves—legacy of our family’s dialect, the little black slaves lived on, exported to Africa in my mother’s language.

There are days like today, when I curse my memory. Mom always tells me: “You and your father have an elephant’s memory.” I curse my memory, which is causing me to remember what she wanted to forget and which made us return to Verona to visit her parents’ old house. My brother is about to be born, it won’t be long now. My mother has had a difficult pregnancy and prefers to give birth close to her mother, in a civil country where there are good hospitals and everything.

We’ve just arrived, only four years have passed since we moved to Somalia. She’s still a girl; she’s only twenty-seven years old, and she’s wearing a large light blue dress with small white flowers. Her hair is incredibly long, and I passed my lice onto her; that’s why Grandma has to use vinegar and a fine comb.

Luckily she doesn’t have curls like me. I really wish that I had long hair like a mermaid, but Mom tells me that she really can’t unkink my hair, I’ll just have to wait until I’m old enough to take care of it myself. Now my grandmother is brushing Mom’s hair with patience, and I observe the little dark creatures wriggle out into the bathtub.

My brother is born, enormous and healthy. Our stay in Verona lasts a few months and when it’s about to end, lots of people come to say goodbye and bring us gifts. Here’s the priest, the one who baptized me and married my parents despite the fact that they practice different religions. He has brought me, in a box that’s been gift wrapped, a black doll with light blue eyes, a flower crown around her neck and a little straw skirt.

Mom doesn’t say anything, then she smiles and whispers that it’s beautiful, in fact it does have the delicate facial structure of all dolls, its hair black and straight.

But the day before our departure, as we are preparing our luggage, I realize that she’s not putting the doll in her suitcase and I ask her why. And, with a sudden rage—I would almost say an unexpected rage—she replies that it was offensive of the priest to gift me a miniature version of a little savage girl, a black doll that even has a little straw skirt: for no reason in the world would she let the doll travel with us. Let it stay here in Verona at her parents’ house.

Now several decades have passed, my blonde dolls have all gone to war and Mom takes Gigia out of her luggage. She forgot about the little savage part, she’s convinced that it was a toy from my childhood and I’m wondering if her presence here in my new house, with her pastel crocheted clothes, isn’t just a simulacrum of my mother who—through me—has turned into a little girl again, with different colored skin.

Roots and Listening

For many years after the falling apart and the escape, I wasn’t able to tell stories. How could I, a teenage mother who had escaped from a civil war, find the right words to describe the horror and the fear, to inspire the empathy and not the terror of my peers, whose worries in that moment were as frivolous as mine were vital? I latched onto studying. My mother, an Italian, was assigned a teaching job in Pécs, in Hungary, our destination after a brief stay in Verona, her hometown.

I had only a few months to prepare for the esame di maturità as a private student. I could do it. I just needed to remain glued to my desk the entire day. I kept the crib close or the baby attached to my chest. I remember the first morning: voices arrived from the window like birdsong. A melody never heard before. The country had just gotten out of the Soviet Bloc, but the traces were still evident. They assigned us an apartment in a neighborhood in the projects. It wasn’t pretty. I rarely went out and my hands bled because of the cold. The people, however, were welcoming, generous. Or maybe I was simply living everything as if it was a benediction. One day a girl who was studying Italian asked me: “What do kids do for fun in Italy?” I didn’t know and so she was disappointed.

The evening was the time for phone calls. During the escape we lost contact with many people: my sister, a brother-in-law, my favorite cousin, my own mother. We reached out to each other, we exchanged news. We felt lucky, those of us that had made it. Because leaving all of a sudden, abandoning your home with the beds still unmade, my young husband who dreams of being reunited with his newborn son, your best friend stopped at military checkpoint, loved ones who risk their life like you risk yours, this isn’t something that you choose.

In Mogadishu war had been threatening for months now, but it was precisely the day that I gave birth, in December 1990, that the anti-governmental forces occupied the airport. I was walking through the hospital hallways to calm the contractions while stretchers arrived full of injured people. I averted my gaze. A boy said to his friend, pointing to me, “Take a look at that one, she has an Italian mother, she could have left a while ago, what is she doing here?” The gynecologist told me to muster my courage. Water and light were missing, the doctor wasn’t there, but I was young. I could do it. My son was born saluted by the triumphant shooting of firearms.

Later on, when all at once silence fell, I was together with him, lying down on a cot. I admired him and then admired him again, almost as if he was a miracle. And suddenly, for the first time in my seventeen years of life, I realized that I was afraid. A new feeling, fear, which I'd never felt before. Not even when, just a year ago, I would run about the city streets, taken by surprise by the curfew. I believed I was invulnerable. But now I had something very precious to save, a sacred relation. Many years have passed since then, most of them spent in Italy. And I firmly believe that you find refuge or shelter whenever you find someone willing to listen to you. Because only then do we stop being strangers and begin to put down roots.