It’s true I have it easy in this respect. From the start I’ve taken care of everything, I don’t let anyone make decisions for me, I politely decline offers of help and, above all, I go at my own pace. His small apartment on the top floor of a five-story building with no elevator, a charmless social housing complex built in the 1970s, had just been paid for, and I’m in no hurry to get it off my hands. I spend weekends here alone. Sometimes I set up for a week or two with my wife and our two daughters, though we never stayed for longer than a meal while he was alive.

In ten years, I’d slept here only one night, on the living room sofa I now occupy, leaving it folded out even in the daytime. I don’t sleep in his bed, I don’t wear his clothes. But I eat off his dishes, I help myself from his wine cellar, I listen to his music, to his records, all the leftist singer-songwriters who shaped my childhood years spent by his side. I nose around in his mess, I rummage, sort, file, tidy, toss out. Sometimes I even enjoy it, I can find a kind of thrill in it, as one does in any job that involves prying into someone else’s affairs—an understandable response. And it’s true that there’s no shortage of material. There are people whose house can be put in order in less than an hour, there are those who keep nothing or who’ve never had much. But my father’s apartment overflowed with boxes, binders, notebooks, folders, pouches, satchels, suitcases, all more or less carefully organized in closets and on shelves. He kept everything.

At first I thought I might find a surprise or two, uncover some little treasure or secret from his past, but as I progress with my task, I’m struck more and more by the coherence of his character. Everything is in keeping with what I know about him, with the image I have of him. Everything is consistent with the principles he wore on his sleeve. Everything is just like him.

He had his own microcosm, his own world. A world he didn’t build alone, and of which he was by no means the sole representative. A bubble—like those that exist everywhere, for all of us. A bubble that wasn’t totally cut off from the rest of the world. What they call a little world.

My father’s little world seemed to have been designed precisely to protect him from the larger world, maybe not to fight it so much as to remain as free as possible from the dominant values of the era, consumerism and capitalism. This little world was made of social activism, of political and civic engagement, of French chansons, cultural outings, and walks in nature.

*

It was during one of these walks—alone in the forest, a few kilometers from his place—that he slipped on a steep, wet slope and hurtled down some twenty meters without a tree or a shrub to grab hold of before falling into the void, off the edge of a small cliff three or four meters high, and cracking his head open on a slab of limestone near the source of the Ruisseau de la Baume. He stayed there for three days, and no one was really worried about him because he was on vacation and he was single. Some people from the area finally reported the car parked on the side of the road, and since he’d left a window rolled halfway down, the police were able to unlock the door. A dog was let inside to sniff out his scent, and it guided them to his body.

Yes, that’s right, it was a dog that led them to him. And probably a big dog, a German Shepherd or something—I imagine it jumping wildly from seat to seat and burrowing its nose in every corner of the car. Except that this was my father’s car. And anyone who knew my father knows that never in his lifetime would he have let a dog into his car.

The problem wasn’t with the car; the problem was with dogs. He couldn’t have cared less about his car. He’d just bought this one; for the first time in his life he’d paid for a new vehicle, taking advantage of a trade-in offer only to choose the cheapest and least powerful model. He was always complaining about his co-workers who talked endlessly of their cars, who tricked them out or bought a new one every two or three years, how this depressed him because he couldn’t understand the obsession. But what he understood even less was the interest in, let alone the love of, dogs. He hated them. The presence of a dog irritated him to no end, drove him literally crazy: he could ruin a meal, a weekend, an entire vacation, all because of a dog.

*

According to Officer Bouveret of the Lons-le-Saunier gendarmerie, he died instantly. But as the coroner has it, he moved some distance after his fall. The doctor notes that his body was found not right at the foot of the cliff but about ten meters away, in the streambed that was nearly dry at that time of year. And so it was quite possible he hadn’t died on the day of his accident but the following morning, after hours of agony. The doctor can’t guarantee this to me. He might have woken up a few hours after his fall and managed to get to his feet, only to collapse again after a couple of steps. He might have crawled a few more meters. He might have kept on dragging himself in a half-conscious state.

Officer Bouveret, however, maintains his version of events. When I tell him about my exchange with the coroner and the body’s location a dozen meters from the foot of the cliff, he alludes to the speed my father would have gathered on his way down the slope and to the likelihood of one or more rebounds. He even offers the example of a tennis ball or a rugby ball. I’m supposed to picture my father as a tennis ball or a rugby ball. I try. I shut my eyes and quickly open them again. It all seems a little ludicrous, but what can I do?

The file was closed the night the body was discovered. The public prosecutor didn’t think it necessary to order an autopsy. My father was pronounced dead from an accidental fall in the woods.

*

What I can do is lead my own investigation, return to the scene of the disaster and interrogate the landscape, observe, form hypotheses. I can continue to search through his things, hoping to find a clue, a sign, some shred of proof. I can sit on the floor in his bright living room, with its view of the whole town on one side and the foothills of the first plateau on the other, and wait for a revelation, an illumination. I can get in his car and drive off for a while, spend the day in the Haut-Jura visiting his favorite spots: caves, overlooks, ruined castles, gloomy lakes in the middle of a densely wooded nowhere.

When I go on these little outings, I could take my own car, but I prefer to drive his, the same car his parents and siblings are so eager for me to sell. I don’t really know why, but since his death, the matter of selling the car has become an obsession for the family. It’s the first thing they want to talk about when I see them: and the car, then, still haven’t sold it? They understand that for the apartment will take some time, I tell them and everyone else that there’s so much stuff to deal with, that it’s everywhere, in the basement and the garage, spilling from the closets and the shelves. I wonder what they imagine, since none of them has ever set foot there—but at least they understand. For the car, though, it shouldn’t be all that hard. I just have to make a stop at the car wash and hose off the body, do a quick vacuum of the interior, cobble together my little ad on Leboncoin, and that’ll be that. But I don’t want to deal with it right away. I’d rather drive through the Jura in my father’s car than in my own. The reason is simple: in his car, I’m a real Jurassian. No one takes me for a tourist. That’s how it is here, and maybe it’s the same everywhere; at every red light, at every stop sign or crossroads, if I pass a pedestrian, he won’t be able to stop himself from eyeing my license plate. If I’m at the wheel of my Peugeot 307 registered in department 69, he’ll give a little smirk and I’ll want to get out and tell him no, I was born here, I grew up here, I lived in the Jura for twenty years, don’t take me for a tourist, come on, seriously, I’m one of you. But in my father’s Seat Ibiza registered in the 39, I’m laid-back. In his car, I feel legitimate. I can even curse out a lost-looking tourist, laying on my horn.

*

As I approach the first plateau, I always glance at the large sign that flashes the number of traffic deaths in the department since the start of the year. The roads in the Jura are deadly, and this one, stretching between Lons and Nogna (home of the New Look nightclub) is particularly bad. The roadside is lined with flower-adorned crosses marking the sites of fatal crashes. It sometimes reminds me of the opening credits of Twin Peaks, the image of a road sign at the entrance to the mountain town where the story unfolds: Welcome to Twin Peaks. That sign displays not the number of traffic deaths but the town’s population: 51,201. There is no town so big in the Jura. Twin Peaks is three times the size of Lons-le-Saunier.

The David Lynch series often gets brought up in attempts to describe the Jura. The pine forests, the sawmills, the flatbed trucks loaded with logs: the parallels are clear. But the comparison is always made by an outsider. I had to leave the Jura myself before the place where I was born, where I spent the first twenty years of my life, could bring any work of fiction to mind. Before that, it was home—it was home and so it wasn’t something you discussed, you didn’t compare it to anything else, it didn’t need to be described. There was no point in telling stories about it, let alone criticizing it, because it was all there was. It was the only place there could be, since it was there that I’d always lived. It was the only place I knew. It was the center of the world, no more and no less.

I had to go away to realize it was possible not to know how to locate my little department on a map, or even to have no idea it existed. That you could eat La Vache Qui Rit without knowing it was made in Lons-le-Saunier. That you could sing “La Marseillaise” without having a clue that its composer, Rouget-de-Lisle, was born here. Just like my father and his seven siblings.

*

They were all born in Lons-le-Saunier and grew up in Clairvaux-les-Lacs, some twenty kilometers away, in a housing estate at the edge of the village. My grandfather worked all his life in the different factories in the area, alternating between wood and plastics, the region’s two main industries. In those days, there were four sawmills in Clairvaux; now there’s just one, the Martine sawmill, where my grandfather worked for a few years (there and at Janier Dubry, which stood where the Atac supermarket is now). He worked for the longest stretch at Berrod, a plastics plant in Meussia, starting on the presses used to mold faucet knobs that were shipped to Algeria, then moving on to pot handles. He stayed there for nearly thirty years making Bakelite pot handles, mainly for Tefal. He often brought work home with him to make a little extra money. The living room was filled with crates of pots and handles to be assembled. The kids would roll up their sleeves and help out.

What I know of my father’s childhood is that the neighborhood was full of large families, that the women didn’t work, that it was crawling with kids; now there are only elderly people, and the housing estate is in shambles. I know, too, that my father was in the same class, for all of primary school, with a young Jean-Claude Romand—the one who assassinated his wife, his two children, and his parents after fooling them into believing for 15 years that he was a successful doctor and researcher with the World Health Organization, when in reality he spent his days holed up in his car in different parking lots at the edge of the woods. Jean-Claude Romand was born in Lons, the same month and year as my father, and grew up in Clairvaux, in a bungalow not far from the housing estate. When the story was all over the news, my father took out his black-and-white class photos to show me. But they hadn’t really been friends.

Jean-Claude Romand’s parents are buried in the cemetery just behind my grandparents’ place. Their house has remained empty for more than twenty-five years; it’s only just been sold. In the village, they still call it “the house of the crime.”

When I stop in Clairvaux for a meal, there’s always a moment when the conversation turns to the macabre news stories that have shaken the area over the past few decades. Besides the Romand affair, there’s the story of that young woman who, leaving a nightclub, was kidnapped by three guys—one of them a minor—who raped her and bashed her head in with a tire iron. As if that weren’t enough, it was the girl’s father who found the body some three hundred meters from his home, in his own cornfield. That was four years before the Romand affair; I was six. There had been a big gathering at the Place de Clairvaux and we’d released white balloons.

*

On each of my excursions, when I go out walking in the woods or in search of a particular lookout point or village, I stumble across all manner of religious symbols and edifices. I’ve grown so used to them that I don’t even register them anymore; I’ve become unaware of their omnipresence. Giant stone crosses covered with lichens in the middle of the forest, oratories, niches, statues of the Virgin in every size, churches and chapels galore. Oddly, I find myself associating them with the fountains, wash houses, and monuments to the dead that serve as landmarks in our villages but are otherwise mostly useless now. You could even include all the ruined castles on the hilltops that overlook the last remaining farms, now surrounded by an apiary, a water treatment plant, a fitness trail, a new housing estate.

Arriving in Orgelet, I notice that Janod, the large manufacturer of wooden toys, has changed its brand name from Jeu Jura to Juratoys.

At the roundabout on my way out of Orgelet, I take the exit to Cressia in search of the famous manor house that my father often mentioned with a smirk. If you don’t work hard at school, I’ll send you to Cressia, he’d say.

The residence houses a private Catholic school, Notre-Dame-de-l’Annonciation. The entrance gate is open, but I park outside, on a forest path, and enter the grounds on foot. The road climbs windingly toward the castle, which is perfectly preserved—its immense wooden gatehouse, its keep studded with machicolations and its little barred windows all intact. I don’t want to come too close; I stay at the edge of the woods and move slowly, jumping back when a voice calls out.

“Sir, are you looking for something?”

A nun is standing right in front of me. A real nun, with a white wimple on her head. I wonder where she came from, this one.

She squints at me. “Sir, you seem lost. What exactly are you doing here?”

“Uh, well, I’m walking . . . ”

“You are not on a walking trail, my dear Sir.”

“Ah, sorry. It’s only that . . . I just wanted to see the grounds again. I’m a former student, actually, I went to school here.”

I’m startled by my own response; I don’t quite know what’s gotten into me. Now I’ll have to do my best to keep a straight face and appear credible.

“My good Sir, do be informed that Notre-Dame-de-l’Annonciation is an establishment reserved exclusively for female pupils.”

Well, that’ll teach me to be a smartass. Maybe I should tell her I’ve transitioned . . . No, I have another idea.

“It was a very long time ago. Long before you were here. By here, I mean here, uh, here down below. It was several hundred years ago, in another life . . . ”

This does not amuse her. She doesn’t even take me for a nutcase—she just stares at me with her light blue eyes as if I’ve cornered her, as if she were trapped. She finally looks at her watch.

“It’s time,” she says, and starts walking quickly back toward the castle.

Emboldened by this odd encounter, I continue wandering through the forest. A little farther on, I discover a small amphitheater covered in a thick layer of moss. I sit down and take a moment to roll a cigarette. I check my phone: one of my father’s brothers wants to know how I’m doing. I start texting a reply when I hear the bell ring and a few engines start humming behind me. Abandoning my text, I retrace my steps and along the way witness a procession of black four-by-fours driving up to park around the castle, its gatehouse now open. Groups of navy blue-clad girls of all ages come out skipping, flanked by two nuns sporting the same uniform as my friend from before. The parents gather their offspring and the four-by-fours make their way back down in single file. I make sure to glance at the license plates—the cars come from Switzerland for the most part, but I do see two Jurassian plates.

I leave the grounds, too and walk back to my car—or rather, my father’s car—and grab my phone to finish replying to my uncle. Since I’m not far from his house, I tell him, I can come by for coffee if he’s free. He answers in an instant: we’re here, we’ll be waiting for you.

*

My aunt offers me a homemade cocktail made in her Thermomix, with rum their eldest daughter brought them from Martinique. I’ve never been to visit my cousin in Martinique, or any of my cousins who live in Australia, Panama, or Vietnam, for that matter.

Of the eight Bailly children, including my father, six still live in the Jura. But almost all of the grandchildren have fled halfway around the world. I’m one of the few who haven’t moved quite so far.

My aunts and uncles go to visit my cousins once every five years and bring back bottles of rum, along with colorful wooden statuettes and dried turtle shells that join the few porcelain dolls and crystal swans arranged on their shelves. They witness their grandchildren’s first steps via Skype, which they pronounce the French way, skip, making everyone laugh. But they count on spending more time with the kids once they retire.

My uncle works at Meynier, a luxury jewelry manufacturer in Lavans-lès-Saint-Claude that produces for Vuitton, Chanel, and Chloé. Each time I introduced him to a new girlfriend, he would give her a necklace and a pair of earrings from the factory—slightly flawed pieces, the defect barely visible. My aunt has long been a secretary at Péterlite, in Clairvaux, a Plexiglas plant that my father told me was known for polluting the big lake with its waste, full of heavy metals: lead, zinc, mercury.

Come to think of it, Louis Vuitton: another famous Jurassian. The real Louis Vuitton, who died more than a hundred years ago. He was originally from Arinthod, which is home now to the massive Smoby factory—another toy maker.

When my family gets to talking about work, I try not to butt in too much. I could say that I’d worked at Smoby, but it was interim work, brief gigs, a few months here and there. When I stop at one of their houses, I prefer to ask questions about the past, with no real agenda. I like to get them talking about their youth, an easy opener. It’s long ago and at the same time the memories are vivid, so they’re not shy about divulging things. They tell me about the dances where most of the couples got together: the soccer jamboree, the firemen’s ball. They tell me about everything that had pissed my father off at that age, everything he shunned, everything he refused to deal with. They tell me about all the stupid things they did between the ages of fifteen and twenty, their first car accidents, a stepfather’s 2CV smashed into a tree right in the center of Champagnole. They tell me about the kermesses, the village street fairs, the traditional fêtes. The Soufflaculs, for example.

The Soufflaculs, or ass-blowers, in Saint-Claude, is a sort of carnival where men dress up in vintage nightshirts and caps and arm themselves with a bellows, those old-timey devices used to fan fireplace flames. They use it to blow air under the women’s skirts, supposedly to ward off evil spirits—to chase away the devil lurking there, in other words. This takes place every year in April and attracts huge crowds to the streets of Saint-Claude. Last year, the festival had made the front page of the Progrès du Jura: the headline was “Soufflaculs Madness.” The next week, it was my father’s turn.

*

After my first meeting with Officer Bouveret, I had to hurry to choose a funeral home. I was walking through the town center when I stopped short in front of one of those aluminum sidewalk stands that display the covers of gossip magazines and the dailies. A Le Progrès poster read: “Man’s body found at the foot of a cliff.”

I went into the bar-tabac and grabbed two copies of the paper; the story was on the front page. The headline was the same as the one on the poster and beneath it, a large photo showed gendarmes and firefighters, along with two men in plain clothes, pushing a stretcher. They were making their way down a leafy path in the direction of two vans parked on the side of the road. The caption said that the victim lived in Lons-le-Saunier, that he was originally from Clairvaux-les-Lacs, and that his body had been found in the Revigny forest after a two-hour-long search. Leaving the shop, I tore the poster from the aluminum stand, then walked a hundred meters to do the same thing at another kiosk. By the day’s end I’d torn down a dozen posters, all of which I immediately ripped up and threw into the nearest trash can.

The next morning, though, it was the same thing all over again—every sidewalk in town displayed news of the incident: “Sexagenarian’s death appears accidental.” The article informed us that an accident scenario was the “most likely” lead. My father became “the sexagenarian,” reduced to the rank of an anonymous figure in a local news item.

*

It was by studying the front-page photo of Le Progrès that I understood how to find the place where he was discovered. In the speech I wrote for the ceremony, I said a few words about this dark and sloping forest with its loose soil, about the small cliff and the source of the stream, about the limestone slab where he was found laid out on his back. I described it as a powerfully evocative setting, a landscape that speaks to the imagination, an unspoiled and magnificent wilderness. A few days later, some of my father’s friends came by the apartment and told me they didn’t share my point of view. They found this forest frightening, sinister, cold, dry, dark, deathly. What had happened surely played a role in their perception, but in any case it wasn’t the sort of place where they’d go walking just to feast their eyes.

It’s true that my father didn’t slip on a bunch of grapes on the slopes of Château-Chalon. What I mean to say is that he didn’t die in a postcard setting. And yet there’s plenty to do in the Jura. It’s a haven for amateur photographers who come with their zoom lenses to capture the fall colors, the fan-shaped waterfalls, a chamois perched on a rocky outcrop. My father was not the photographer. My father was the chamois.

I, too, wished that he’d gone walking along the greenway, slightly higher up in the forest, that day. On the greenway, at least, there’s no risk of slipping. But to opt for the greenway would mean constantly having to step aside for dog walkers and families on bicycles. I didn’t know if my father’s friends saw what I was trying to tell them, and to illustrate my point I threw out a few corny analogies, in the way of: my dad on the greenway would be like giving a soapbox racer to a rally driver, or like dropping a deep-sea diver into a paddling pool, like asking an astronaut to jump from a . . . to launch himself onto a . . . I was starting to get my wires crossed, but I think they understood. What I wanted to say was that it was a place he loved, that he felt at ease in those woods, and precisely for their dark and rugged and inhospitable side. I wanted to say that this forest was a lot like him, that it was a reflection of him, of who he’d been, a solitary guy, a bit of an outsider. Because it was this representation of him that I so wanted to defend at that moment. I was clinging to the idea that he’d died in the woods as a sailor dies at sea. The forest that takes the man. My father, the adventurer.

The truth is likely less romantic. I think I know what he was doing in the Revigny forest that day.

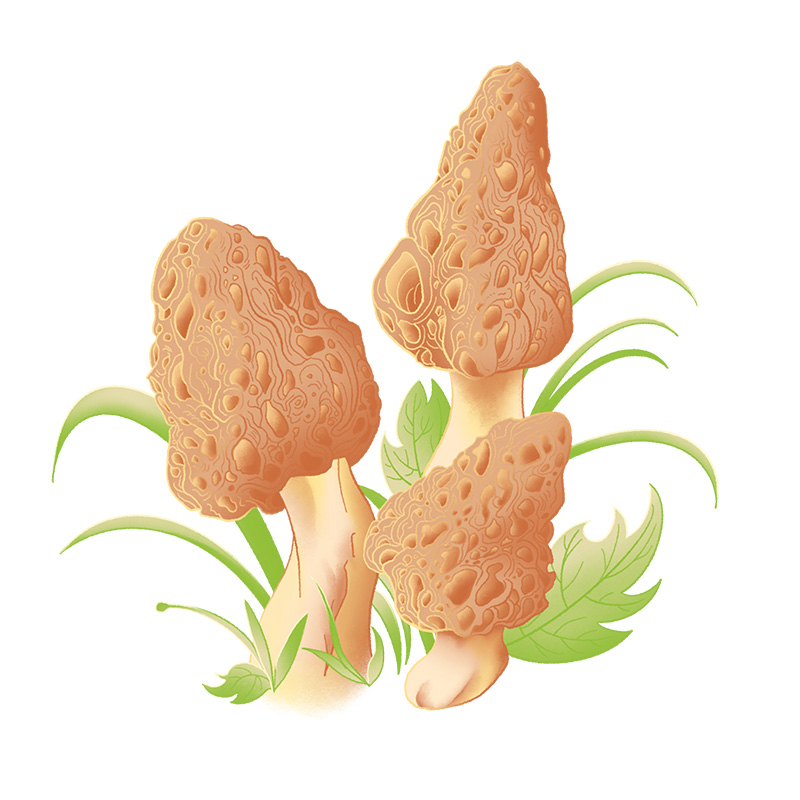

During that first meeting with Officer Bouveret, we had mainly discussed the shoes he was wearing—shoes that weren’t right for the terrain, lightweight oxfords with smooth soles. The officer also informed me that a plastic bag had been found beside his body. He believed that this plastic bag left no doubt as to the reason for my father’s presence in that place: he had gone there to hunt for mushrooms.

The scenario that took shape, then, was this one. My father takes his car to go walking in the Haut-Jura, maybe around one of his favorite lakes. On the way, he stops at the side of the road overlooking a sloping and densely shaded forest known to contain delicious mushrooms, those coveted morels. He doesn’t plan to walk far and doesn’t think it necessary to take his hiking shoes out from the trunk or to bring his backpack, which he leaves on the passenger side seat—inside it, the thermos of tisane and the packet of biscuits I later found. He takes only a plastic bag that he hopes to fill with a few treasures. He goes down into the woods and feels calm, at home. At a certain moment he finds himself on the side of a steep slope, faced with a choice. He could turn back. He decides to chance it.