I like to think of writing as something that won’t stop growing. Like a seedling that cracks open, again and again, that extends both up and down, in the hand that writes (the soil, the roots) and in the hands that enact the reading (the boughs, the leaves). I started writing these letters as a kind of ritual, an engagement with myself and with the hands receiving these small fragments in their inboxes via the online tool TinyLetter. I used to wonder all the time what would sprout on screen or page if I sat down to write with no limits or rules, if I let my fingers pull me along, my eyes almost closed. I often think of the act of writing as she who walks in the wake of the rising-falling howls of a wolf that she never sees.

For María Gabriela Llansol, her notebooks were, on the whole, a sort of featureless terrain over which the seeds of writing have already been scattered, though we—from above—can see nothing. As the writer continues to set down her notes, fragments, outlines, and sketches, germination takes place and the ground begins to teem with shoots that, this time, can be seen from above. As Llansol once wrote, it is here, during this process—which might at first seem chaotic and anything but calm—where writing is truly awakened. Honest, true, and boundless writing that for decades has languished in the shadows in Portugal and which now finally has the recognition it deserves.

In some way, she sensed this, and wrote the following in her notebooks while in exile:

I, Gabriela, at the moment of the great decision, determine that I have no parameters:

- I am a woman with no children

- I am a writer (I prefer scribe) with no recognition

- I am a stubborn and steady worker with an unknowable material life

The title of one of her notebooks is The Next Word. I wanted to call these letters by the same name, for both the immediacy with which they have come about and the way they have followed one after the other. And, I suppose, as a nod to her and her writing, so often a companion to me.

FIRST LETTER

What We Weren’t Able to Say to Each Other

I write and I know who is on the other side.

It’s a comforting feeling, like a brief set of brackets amid so much immediacy.

I remember my first diary, which wasn’t really a diary, but rather the letters that four primary school girlfriends wrote to each other in the same notebook. The only condition was that one of us had to write in it every day for a week. On Mondays, the diary was passed to the next one of us. And so we grew up, without realizing it, waiting for the first day of the new week—to read ourselves among ourselves, to place on the page what we often weren’t able to say to each other during the day.

I don’t know where that diary is. There were many, but I kept the first. I can picture the cover, adorned with little red roses, too red, too innocent, too small. That diary is the only thing I still have from those years, and it’s at my parents’ house, stored well away like something that’s not particularly important but that you don’t want out on display or at hand. If I wanted to retrieve it, I would have to engage my body, make an effort. Open a wardrobe, pull up the handle of a huge overhead storage space, take down tons of books, shoes, clothes, magazines, and finally, at the back, I would be able to just scrabble at it with the tips of my fingers. But I would still have to stand on my tiptoes, really push myself, make one last effort.

It might sound bad, but the thing I miss most from those days is writing in that diary. Now, here, as I write these lines, I wonder if I used to write so often because I knew there was somebody waiting to read it. Relief, security, complicity? I don’t know.

Yesterday, eating at the bar under my house, a woman—smiling, a little nervous—asked me if I would please keep an eye on her parents; she couldn’t be sure of them. She was going to the bathroom, but she would worry if she left them on their own. That combination of terror and tenderness on her face stayed with me for the rest of the day, and I am still thinking about it today. The way she moved her hands, her joy on coming back and seeing her doddery old parents, it was like it was the first time she had seen them in such a long time.

I don’t know where I’ll get with these letters, if they’ll count for anything, provide pleasure, company, or simply end up in the spam folders of multiple inboxes.

For now, I hold on to this line I translated from María Gabriela Llansol:

Is surviving by writing to be a blind way of serving humanity?

SECOND LETTER

I Was Born an Adult and I Will Die a Child

For months now I have been obsessed by an image of the Portuguese writer Agustina Bessa-Luís. Actually, it’s a still from the documentary about her, Nasci Adulta e Morrerei Criança, which means something like, “I Was Born an Adult and I Will Die a Child.” This boundless writer, who is nearing a hundred, appears in close-up in a kind of armchair. Behind her, there is a vast tree.

The branches seem to belong to the woman’s body. As if boughs and body shared the same anatomy. The image also has a particular light to it, as if it were a kind of universal language to define the word home.

Yesterday, my father told me a sweet story I hadn’t heard before. And it is about a woman and a tree. My great-great-grandmother Pepa knew by heart every cork oak and holm oak on her land and, when she realised that she only had a few years left to live, not being able to walk or look after herself anymore, she asked to be taken in a kind of armchair to see the oldest and most beautiful cork oak she had. They were harvesting the cork that year, and she knew somehow that neither she nor the tree would live to see the next harvest.

It’s strange, this language of obsessions and words we spin, gradually making them our own. Since the summer, every time I go to my grandparents’ house, I photograph and record the lemon tree on the patio. I don’t know yet why or what for. My father says it’s just any old lemon tree, but I like to weave a story around its boughs and tiny creatures.

Today, there were already violets in the bed around the tree. My grandmother Teresa used to love them. We picked them and put them in water, in the silver vase for violets she kept in the drawing room. That way the house today was left a little less alone.

THIRD LETTER

Dismantling the Obvious

What’s more, at the beginning of the week I finally managed to file an article—one that meant a lot to me—for a magazine about women and rural life. I can see that I was losing sleep over this piece of work, and on several days, I woke before my six a.m. alarm thinking about it. How vital, and what an uphill struggle, it sometimes is to write about our daily lives, to write what we understand, in the end, about ourselves.

And the body knows it, and cautions us. I had so wanted to go out with my father on Friday—to walk the land with him, to help my uncle with his animals, to visit the vegetable patch that, now that my grandmother spends the winter out in the cold, feels more lonely to me every day. But it wasn’t possible and I had to shut myself away, had to give my body time and space to start again.

Yesterday I started reading The Songs of Trees, the second book by one of my favourite writers, David George Haskell. Here you have an extract:

In the national forests and national parks of the United States, cultural geologies, the processes that create geographies of attraction and of fear, have been exclusionary from the start. These institutions were born from philosophies of Nature that revelled in the imagined supremacy of whiteness and masculinity.

And in this way, dismantling, piece by piece, what we assume to be glaringly obvious, I try to build a house, where the first stones have only ever been men (reading, family, references, friends) and I go about restoring it, piece by piece, with the voices and the hands of all those women who have brought me this far, made me what I am today.

Yesterday my mother came to my house with broth and a sprig of peppermint from our pots. She told me about my brother José, and about one of his friends who, already half an orphan, has just lost her father too.

My mother, upset, said that my brother’s friend had told him that she has already lost her whole childhood. And when she left, a headline on my computer about a seminar in Lisbon with students of Lobo Antunes: “When I was born death did not exist and everybody was alive.”

FOURTH LETTER

Dream-Writing but Without a Pen

Thanks to Claudio Bertoni, in August I started writing down my dreams. I don’t always do it, sometimes I forget, sometimes I write too much. It’s possible that the dream I finish telling on paper has already been distorted out of shape. For months, I’ve been dreaming about a vast wooden table.

It is sturdy, too big, and there’s nothing on it. Not even a blank sheet of paper. I run my hand along its surface. I like the sound it makes, the rub of the spotless wood. In the dream I’m dying to write but I don’t have anything to write with. There I am in the middle, asking myself over and over what life wants from me.

Does having more time to write make one more of a writer? Writing as output, I want to move away from that. The questions return again in my dream and in my day. Does the desk mean for me to write? Where have the animals gone? All those women, who have crept through life and are left voiceless and in the shadows, where are they? Will they write about me? Will they remember my hands the way I remember the skin of all those I have touched? And in my head, two things: “to see a landscape as it is when I am not there,” by Bertoni, and a song I can’t remember by Lispector that sings to me and keeps asking me if life wants me, will want me as a writer this week.

I worked in La Rioja and in Castilla y Leon.

At the foot of Moncayo, I stopped to touch the snow.

FIFTH LETTER

Vertigo Before the Pause

Only 3,687 kilometres this month, the shortest month this year.

I always calculate the number of kilometres I cover in my truck. This last time, which saw me totting them up in order to submit my worksheet for the month and so be able to invoice for it, I realised that haven’t ever considered the hours that I spend driving.

I felt something akin to vertigo. I started to add up, half from the bottom and half from the top, and I was alarmed to think it’s possible I spend more time behind the wheel than awake in my own home.

Yet another Sunday in front of the computer: interviews, articles that leapfrog their deadlines, projects, and a book that is a reproach to dedicate more time to it.

Tonight, before falling asleep on the sofa, I’ll pick up my planner again and, once more, write down everything I need to do.

I will tell myself again the line about carving out an hour a day to write. I will start Monday with enthusiasm, like I always try to. They are difficult and contradictory, sometimes, my work and my writing: they can’t exist separately, but there are also many days on which everything feels like a reproach.

I don’t know how to explain this involuntary feeling of guilt that many women experience when we simply “do nothing.” This feeling that I have observed so many times in my grandmother and in my mother, and that I from time to time perpetuate.

Like that concrete slab that sits atop every dead body, that their families chose to leave on a spot that will ultimately turn to bog. Do they know the weight that they bear?

At least it’s finally raining properly.

SIXTH LETTER

A Poet’s Body

There are words I find difficult to say aloud, to write, to give voice and time to.

These last two weeks, two have prowled round my mind, too much.

The first, at the medical review that I’ve not had done for two years.

I’ve finally been tested for brucellosis and toxoplasmosis: my work carries some risks, ones that, despite not being part of my day-to-day, still exist. And so, from time to time, I have to name them aloud, reclaim them even, so as to perhaps be able to put them where they belong.

The other has brought me to the disappearance, a few years ago now, of one of my closest school friends, and this absurd feeling surfaces again—of wanting to respond to something that has no response.

I never met Victor Heringer in person, but we used to talk over social media, and I had left unfinished a translation of one of his poems for a short-lived project that never fledged. They never said anywhere why.

His body was found on the street, near his house, just like my friend.

Nobody dares to say, to talk, to respond.

We sent each other books at the same time but they never arrived.

I like to think that they met somewhere on the ocean, or bundled at the back of the aircraft hold, or in the sorting bin of some post office. I know that it is impossible for both of them to share space and time, but it is comforting to imagine them like this.

Recently I have also felt the urge to finish the translation, but that’s all it’s been, just a foolish and needless urge. He sent the image of his signature together with the poem.

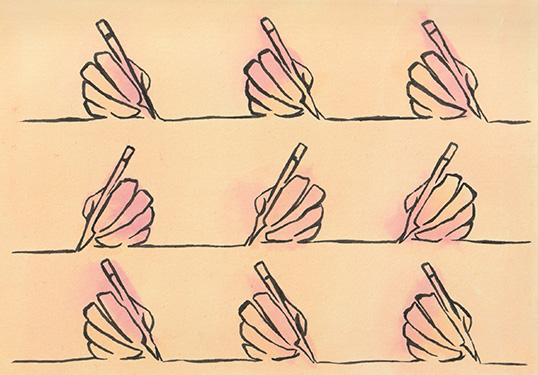

Sometimes I like to open the document and think about the writer’s hand on the paper.

What I liked about that project was talking with the poet, seeing the words grow and change in the other language, looking for sister poems, feeling near to that voice crossing an entire ocean.

Knowing, for a moment, that any single body can be confused with a poet’s body.

Não sou poeta (de Victor Heringer)

Agora que os estalos da adolescência passaram

e a vida assenta como uma cômoda de mogno

agora que os joelhos estalam quando me levanto

sem mulher, sem filhos, mas com emprego estável

é preciso admitir que não sou poeta.

Embora o meu amor esteja solto no mundo

violento, semicego e ferido no ombro

não sou poeta.

◉

Todos me felicitam. Que bom, dizem

vida de poeta é muito difícil.

Logo a gente chega a ser homem

e acaba com as coisas de menino.

A vida afunila.

◉

Eu tinha dois, três truques nos bolsos

de calças compradas em shoppings.

Não soube nunca comprar como poeta

a longa espera por um par de sapatos

sentinela no deserto.

Os sapatos são fabricados e os pés dos poetas passam anos se deformando. Até que um dia cabem.

Por isso qualquer roupa parece velha

no corpo de um poeta.

Por isso estão sempre se desculpando

pelas roupas velhas.

Mas em segredo se orgulham.

Embora eu tenha um corpo

que pode ser confundido com o corpo de um poeta

não sou poeta.

Tenho as pernas fortes e os braços magros.

O torso amolecido dos boxeadores

os órgãos de dentro estropiados.

Mas quem me vê nu instintivamente sabe que não sou poeta.

◉

Não levantei a mão esquerda em golpe de dançarina de flamenco ao ler Jaime Gil de Biedma para os meus amigos,

embora tudo tenha conspirado para isso.

Para que se me entranhassem as coisas.

Concluo que não sou poeta.

Tenho os dedos frios de um técnico em informática

e sou triste como um técnico em informática

mas não sou tão triste quanto um barbeiro.

Eu li todos os tratados da métrica portuguesa.

◉

Assinei dois contratos como poeta

que doravante já não têm validade.

Assinarei um terceiro, como última traição.

Serei perdoado por todos.

◉

Doravante vão reinar o olho e a raiva.

As melhores botas para caminhar na areia

os cálculos de longas distâncias

os treinamentos de apneia.

O amor virá até mim como vai aos jornalistas e CEOs, aos sushimen de São Paulo (SP) que vieram do Ceará – ideais porque têm mãos quentes.

◉

As partes elegem o Foro da comarca de São Paulo (SP), renunciando a qualquer outro, por mais privilegiado que possa ser, para dirimir todas as questões surgidas quanto à interpretação ou execução deste contrato que não puderem ser resolvidas amistosamente.

SEVENTH LETTER

Fear of the Blank Page

I sit down to write and it’s already gone eight. The last light glints in my great-grandmother Rosario’s coffee set, in amongst small piles of books that do nothing but wait, next to the plant pots.

Waiting, lately my life splinters like this: waiting to have time to write.

I can see that these brief letters are a kind of warm-up, a way of shedding the fear of the blank page. It’s no longer cold and my grandmother has returned to the village; I think about her stout legs a lot, and about how when she could still walk she used to have to stop every five minutes to pull up her stockings from where they had puddled around her ankles.

Every time it happened, the wicker vegetable-garden basket would drop to the floor. The vegetables and eggs, just then collected from the henhouse, would also have a rest.

I focus a lot on these moments, these small pauses where life stands still and nothing happens.

This week, Fernando and Andrea come to spend a few days in the village, with my family, to see where the grass grows, to stitch together the book’s beginning with its images. Will the hares come back? Will they fill their hands with corn for the hens again? Will I come upon the poacher’s breath behind the limewash? Will my mother turn little girl again, picking olives? And my grandparents?

Will they recognise somehow this kind of invocation?

I shut the book by Gabriela Ybarra and a phrase continues to resound:

Sometimes, imagining has been the only option I have had to try to understand.

EIGHTH LETTER

Blood and Mud Staining the Snow

The best thing about Sundays is that there’s no rush to have breakfast. Nobody is waiting, the street is still sleeping, and my only company is the sound of the stove-top coffee pot about to blow.

I search for the book that I lost last night in bed when my hands decided to drop and sleep came. Sometimes I have to go back pages because my dreams have become confused with what I read the night before.

I know that last night I read sludge, blindness, razors, rattling, window, engine, puncture. In the dream, I was driving and driving and it wouldn’t stop snowing. Too much mud. The colour and the texture of the dirtied snow made me sad.

We think about snow and we only ever imagine a pure emptiness, so white that it warms us, a magnet we’d open our arms to without a thought. But there is also pain and struggle in snow, blood stains and mud stains. Tracks, remains, some sign of the last movements of a wounded animal.

In February, I had to pull over on the hard shoulder to get out for a moment and touch the snow, dirty it with my feet and hands. It’s strange, how rarely we see the snow and how often we think about it.

Today again, waiting for my coffee, alone, I’ve thought about everything that illuminates and reflects, about everything we believe because of light. I go back to the book I started yesterday, I open it on the page I marked, I reread: almost everything that surrounds us is susceptible to being transcribed, made subjective, channelled through the sensitivities of each and every one of us.

And if death is just a heron feeding on the light?

NINTH LETTER

So Far and So Close

Every time I travel by train I find myself retreading the same ideas, images, questions. I feel a kind of tenderness and sorrow when AVE lines pass right by so many towns. I try to imagine what it means to someone’s daily life, a high-speed train passing by so close and so far at the same time.

Close, because perhaps in a way they do enter, too sharp a thrust in the residents’ lives; I often wonder how many of them use this kind of service and the journey they’d have to undertake to the nearest city to get on board and begin their trip, use the service that they see and feel every day.

And so, also, far. The lines intrude but don’t stop. Not here, not for you.

And the dead? There are so many graveyards so nearby . . . to the point that their whitewashed walls and their cyprus trees as good as border the tracks, as if they were a kind of security, a form of assurance with speed.

Do they shudder in their little boxes every time a train passes? Are the birds aware? Might the steeple-top stork build its nest differently since the Forastero began to slice through its home? Do they tremble? Do they consider it? What does it seem like to them, how do they picture it?

On the way back, trying to write, my father’s sent me a WhatsApp message to tell me that he thought of me today when he discovered a crested lark’s nest (Galerida cristata) with four eggs in the countryside.

Immediacy is not all bad: writing words like to miss, to think, to love, to remember . . . that sometimes we struggle to say. Another breed of language that emerges, while the train keeps moving forward and I shut the computer. Then I smiled when I encountered Jim Harrison winking at me from Dalva: the need to put something into writing arrives after the fact itself; the event registered with calmness bears a weight of calmness greater than deserved.

In the room where I’ve spent the night, a beautiful collage by Carmen Berasategui has watched closely over me. How could I not think about everything that I carry with me, my grandmothers, my mother, the women I love and admire. About that family tree—so essential—that grows and grows.

TENTH LETTER

To Survive by Writing and Fighting

A shadow has hung over me for days. It’s making it difficult to write, talk, articulate what’s going through my mind. I can feel a kind of heavy knot, hauling around a mix of fury and surprise.

I don’t know if it was in the first letter where I highlighted a question that the Portuguese writer María Gabriela Llansol posed in one of her diaries: Is surviving by writing to be a blind a way of serving humanity?

These days—of such fury and silence—I have returned again and again to that question. I have tried to encompass it, make it a little bit mine, understand it, embrace it. Create a form of language from it, an invisible tongue, a kind of hand to seize hold of and write with.

I cannot recall the precise moment I first feared losing my parents, my siblings, and my grandparents, but I can remember every second of the first time that someone tried to assault me. The light in the empty metro carriage, the voice announcing the next stop, the song that I was listening to until everything froze still.

In the seconds before, I had been downplaying—over and over again—the fact that a man had sat down right next to me in a totally empty carriage. I kept telling myself, everything’s fine, María, don’t assume the worst, there’s no reason for anything to happen. My silent conversation with myself was shattered when I felt hands roughly rubbing my jeans: my thighs, my waist, my ass, my vagina.

I was silent, stilled, I turned to stone.

I was incapable of uttering a word, of moving a finger.

As if I were merely a spectator and this just another process to undergo. Suddenly, I heard myself screaming please! when another boy opened the carriage door. My attacker left like a shot and got off at the next stop.

I couldn’t move, couldn’t look up. I had become the prey who escapes but lingers near the hunt. That touch, on my skin and my clothes, took a long time to fade. In fact, I never wore those jeans again. When I got home, I looked at my clothes on the bed. I blamed myself, despite myself, for my clothes, I wondered what could have been the trigger, and worst of all, for months I couldn’t stop reproaching myself for the total passivity that had taken hold of me when it all happened. I never caught that line again. I’d rather it took me an hour longer to get to Lisbon Airport than catch that line again.

It’s unthinkable how these events shape our map of journeys and decisions. How they belittle us and keep us down, like the shadow that for days now has come back to hang over me. That’s why, reading the hashtag #cuéntalo, Llansol’s question has surfaced again. How painful, but how urgent. I think about all the women around me and I just want to tell them to talk, to write, to tell, to shout.

To do exactly the opposite of what the sixteen other men in the WhatsApp group did and only cheered on, laughed, applauded, or looked on enviously. To raise their voices like they have done on the demonstration days in so many places, to smear their faces with war paint, to reclaim the meaning of the word manada—wolf pack—to support one another, to not stop fighting.

How I would love to write to Gabriela and answer her yes, we are useful like this, shouting, fighting, defending ourselves, telling, writing. But not blindly, no dear Gabriela, but clearly and vitally. Yes, surviving by writing and fighting, continually.

Every day I believe more in the margins: those margins that sustain us and safeguard us. The photo, on the way to work this week on a track in Extremadura. Also azure-winged magpies building their nests, bee-eaters, European rollers, diminutive birds of prey high on telephone wires awaiting their prey, storks behind the farmer in the harvests.

The new shoots, another year, as if nothing.