We always did this whenever my son Rebo and I met. I was sure he’d ask me to buy a new Beyblade, that’s why I saved up for him. It’s roughly 30 to 50 pesos or more depending on its design, energy layers, forge discs, and performance tips. I’d be lifting weights because I was sure Rebo would like me to carry him whenever we’d visit his favorite store at our barangay’s local market.

The toy store’s half a kilometer away from my mother’s house where we would see each other often every Saturday. Rebo asks me to drop him down when we’re both in front of the store so he can point to his favorite toy. As we approach, the seller welcomes us with a smile. He’s known us for a long time, even the schedule of our visits. He’s ready to pitch in the newest Beyblade that Rebo might like to buy. Rebo always looks first at the colors and design of the energy layers and the forge discs. Plastic or steel? That’s just an afterthought. But for a long time now, Rebo chooses the plastic ones. He plays with the Beyblades way more than the other toys, like trucks and cars. Maybe because they’re so much smaller. And unlike the latter, Beyblades can be carried anywhere: just pull them out of your pockets.

I was sure Rebo would pull out lots from his pockets. While he’s getting ready for a “battle,” I’d sometimes check my pockets and only feel my hands, remembering that I gave everything to him. The game is a contest of endurance, spinning longer than the opponent inside a plastic bucket called the Bey stadium. If the opponent’s Beyblade flies out of the ring, they lose. If the opponent’s Beyblade stops spinning first, he loses. Yet, unlike the other kids who give up after a defeat, Rebo continues to fight. He’ll grip the saw-like teeth of the ripcord harder than usual. He’ll tighten the lock of the Beyblade launcher as if he’s holding a gun. And when the game begins, he quickly pulls out the ripcord from the narrow hole, releasing the Beyblade like a flying saucer spinning down to the platform to fight again.

For four Saturdays, my youngest son fought battles with his Beyblades in the field of play. For eleven months, he fought leukemia in the hospice of feelings.

*

To a teacher like me, April is summer break. To my youngest son who will be turning four years old, these are the days he’ll play outside with his cousins.

It was the last week of March 2003 when he ran a fever for a week. When the fever broke, a few days passed and he lost his appetite. Then, he turned pale. By the first Saturday of April when I saw him again, he didn’t want me to stop carrying him because he got tired quickly. Little by little, bruises appeared.

First, it was on the legs, then on the arms, until these patches spread like wildfire and were found on his foot, chest, and thighs. His lips paled as if soaked in vinegar. The clinic, a few blocks from here, came immediately to my mind. I would have liked to tell the doctor: “I have 500 pesos here and I’ll look for more if needed. Tell me what’s happening to my son!” But even after the fees had reached 3,000—on top of pleas, donations, and debts, three doctors and two clinics—and after I had numbed myself against my son’s screams every time a needle pricked him for a blood test, the illness remained without a name. His heart rate was higher for his age, his red blood count plummeting—these were the doctors’ only interpretations. Failure to diagnose. This case needs more tests. More blood tests and pain. The muscle aches and shivers. Me, my wife, and our family get numb hearing more of these words each day.

The failed attempts at diagnosis were difficult to bear. I had to endure not only the pain in my knees but also the weight I carried in my chest as I stood here waiting in the hospital. Whatever the results were, I must be ready. Rebo’s mother stood in long snake-like lines at the largest public hospital in the country. They were lining up for a hospital card to schedule a consultation with a pediatrician who specializes in diagnosing the symptoms.

That day, Rebo wanted me to carry him, not his mother. This is what he wanted: Even if his Naynay could carry him, what he wanted was for his Taytay to carry him and hold his Ate Kala on my other hand.

“Because it’s Saturday, Saturday should not end yet. Taytay should not leave early because I will have to wait again for another Saturday or his pay day before I see him again. Never mind leaving Naynay for a few hours; she’s with me every day. I just want Taytay to carry me, hold me, tell me a story, play with me, buy ‘ays wis’ (ice cream) and ‘babuygyam’ (bubblegum) for me, and let me take a nap on his chest because it’s just Saturday!” I know these are the exact words he’ll want to say if he could let his young mind and his stuttering tongue to speak.

When Rebo got sick, a year and a half had passed since my separation from Joida. There were many disagreements. We looked in different directions. And money was often scarce: the result of a young and unripe marriage. I don’t want to go anymore into the details of our separation. This is one of those memories I have buried deep in the mud. There came a point in my life when we had to forget the past and be civil for the children. This was when I was living on my own in a place no one must know about. Our kids lived in Joida’s sister’s house. That time, I had the opportunity to teach in a big and prestigious private school for rich kids and I was able to withdraw livable wages from my ATM. And unlike other fathers who leave their children with nothing after breaking up with their wives, I made sure that the larger part of my “two-week’s worth of wealth” went to my two children and what remained was saved up, just enough for me to drink a little beer.

*

It was painful to realize that the undying love I had for my children was not enough to shield them from a deadly attack.

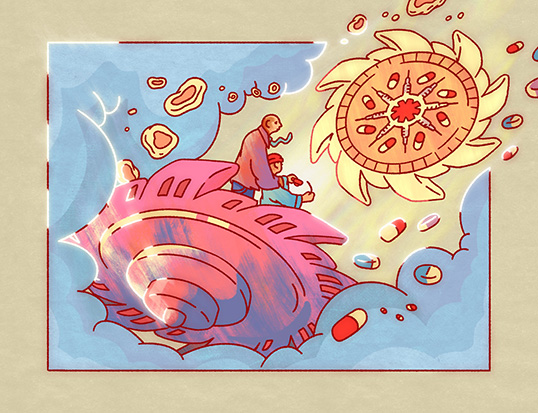

Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia, also known as “ALL,” is a type of leukemia common among children like Rebo. Chemotherapy is the only treatment. A series of cycles for the treatment takes weeks. Induction, consolidation, maintenance: three phases of treatment. Six, four, down to one strong dosage must enter my son’s fragile body. These drugs will kill the cancer blasts that grow inside him. These drugs, blind to anything in their path, can destroy even the healthiest of organs and cause further complications.

We had been in the hospital for two weeks before the name of his disease was disclosed to us. We never left the hospital from the first day we planned to bring him for a check-up, hoping that the doctor would just prescribe drugs for anemia or something else that would make his heart beat normally again. The doctor’s words were a deafening rush of details and interpretation. Yet I managed to somehow process it slowly, notwithstanding my benumbed mind. Rebo’s face flashes before me: he is crying in pain every day during blood tests and blood transfusions. The needles puncture his arms, his feet, his hips, his hands, and any other part where an unswollen vein appears. Blood flows freely in the tubes.

Rebo is a picture of many spots. Small and large bruises, red and dark rashes.

He is a picture of a balding child, losing his hair to chemotherapy.

He is a picture of many fallen hairs swept by the breeze, not knowing where the wind blows.

Radiation or genetics? We were uncertain. Simply put, his bones failed to develop and his marrow wasn’t able to produce enough blood for a long and healthy life. His bones never grew.

Buto, dugo, pesteng buto! Pesteng dugo! No parent would ever want to hear what I heard. My son doesn’t just have diarrhea or fever. He is dying.

*

We stayed in the hospital for a long time. I thought it was a month, then it became two, then three, and then four, until I forgot how many months had passed. What I was sure of, though, was that we would stay longer.

“I graduated with a bachelor’s in education but I can’t find a job.” “Actually, even if you teach right now, you can’t handle it.” “I agree, sir.” “Can’t you afford a rent of costs 300 pesos a day?” “Not really, sir.” “All right, show this form at the Social Services office. To your right.” “Thank you, sir! Thank you very much!”

I have to pretend and lie so Rebo can be transferred to the hospital’s Charity Ward. At least here, Rebo can sleep on a mattress that is much more comfortable than the metal bed with wheels in the Emergency Room. Plus, there’s a TV. If he’s lucky to get the remote first, he can catch up on his favorite show. There are lots of other people watching too: the sick (from the severe cases to the critical), the relatives at each bedside (from the laughing ones to those crying or sleeping), and the visitors (from the hurried to the lingering). In this ward, illness manifests in all people from all walks of life. There are some who live in poor urban areas. Some come from the nearest to the farthest provinces. They hope to get well here. All of them are praying for donations to come from famous yet unnamed philanthropists who sometimes visit them because everyone’s desperately in need, even of a cheap injection.

While the bed and food are free, we still have to buy all the prescription medicines and medical supplies needed for the cancer treatment. Even with my daily grind, I have to stay here to save money. Back then, I was earning fifteen thousand pesos a month and if the Philippine General Hospital had found out, Rebo would have been removed from the charity ward. He would have had to be transferred to a costly private room. I prayed hard for him to be allowed to stay in that place. My greatest expense was all of his medicines, which is around six to eight thousand pesos a week. That doesn’t even include the injections, the dextrose, the tubes, the food that he craved, the laboratory fees outside the hospital for his blood analysis, or my fares. If you were previously bad at math, now you’d probably be the smartest because you’d do lots of accounting for all the cash that goes in and out, letting out a deep sigh at the end of the day.

You would also learn to read strangers. The noisy and the quiet ones beside you, the generous and the parasitic. The mean and happy nurses. The snobbish and approachable doctors. The smart and stupid interns (especially those who pricked needles into my son eight times and still didn’t draw any blood—they deserve my anger. The heartless laboratory technicians who didn’t accept the amount of blood samples even though the doctor approved it (“What do you think you can do with my son’s blood? Scoop it from a bucket?!”), and the relatives who were calm at first then lost their minds from depression. The sick are constantly noisy: either in bursts of laughter or wails of despair, both young and old. The quietest among them? Those intubated souls.

As for Rebo, once the ritual of taking his blood is over, he turns into this frolicsome, naughty kid. “Remove this dextrose from me! I want to visit the other beds!” Often, the people in the ward make fun of him, “Go away, you’re not sick, eh!” He claps back with the bat of an eyelash, pulls out his tongue, and makes funny gestures. After a month, everybody knows “Rebo bulol at kulit” in the Charity Ward.

*

Help poured from everywhere; even the smallest donation kept my son alive.

“Ma, has Tita Naida sent her remittance? How about Lola Conching?” “Kapitan, thank you for the donation, ha!” “Councilor, how do I go again to the Sweepstakes office? By the way, thank you for giving us the collections from the zone leaders. My mother cried in front of them.” “Tita Marilyn, I’ll just pay this when I get back on my feet.” “What? These came from the donation drive of Tita Jean’s students?” “Tita Vic, please take care of Kala for now, ha! I can’t leave Joida alone at the hospital, eh.” “Kala, don’t be naughty. Behave!” “Bro, have you told the gang? Just a few pints of blood will be donated.” “Thank you, compadres! Drinks on me next time. Just eat bitter gourd for now.” “Ma’am, sir, I will be absent today. I need to be at the hospital. Thank you for the kind offering of the Faculty Club and the other departments.” “Sure. You can pray for Rebo at the hospital. We’ll wait for you there.”

We stayed at the hospital for five months until Rebo reached the last phase of treatment, the maintenance stage. It was September, which meant that he would visit the hospital once a month for his chemo. This would go on for three years. By then, Rebo had celebrated his fourth birthday and some hairs had regrown on his scalp. I expect that my son will get well by the time he is seven, a ripe age for going back to school. I am sure he won’t stammer anymore.

Outside, my son seemed like the healthy boy that he once was. Play over here, play over there. Eat here, eat there. Except when we returned to the hospital for a chemotherapy session. Each time a session ended, my son looked like a withered vegetable for three days. He didn’t want to swallow anything except water. He didn’t want to bite anything except an ice cube. “An ini ‘Tay nan aawan o!” (‘Tay, my body’s so warm!) He threw up a lot and felt irritated all the time. He didn’t want noise. He didn’t want chaos. Iritado.

By the fourth day, he was back to normal. He’d wake up early and join me in taking his Ate Kala to school and picking her up at the end of the day. When they got home, he’d play with her. As soon as he got tired, he’d switch to his favorite pastime: slouching on the sofa and watching his favorite children’s show.

Aside from seeing them every Saturday or pay day, I’d call my children every morning and afternoon. And most of the time, Rebo was standing by to pick up the phone. But when the “three days of suffering” in chemotherapy arrived, it was out of sheer luck that he was in a mood to talk to me. I would often ask him if he felt better and he would loudly answer, “Magaying na!” (I feel better!) I would also make him promise that he wouldn’t leave me and his sister Kala, to which he often said, “Ayoo na!” (I don’t want to!) Yet sometimes, he’d joke about it: “Us-o o na!” (I really want to!) Then, he’d sing a song he had learned from TV.

If he only knew how disheartened I was to hear “Us-o o na!”, how my stomach turned from this premonition.

Just like other children, Rebo was excited about Christmas. December had just begun when he asked me to buy new clothes and toys. Before these gifts could even arrive, in the middle of December, we were shocked by the results of his new blood tests: cancer relapse. The cancer blasts had reappeared. He needed to undergo the same chemotherapy again. Everything we had done in the past was for naught.

A new set of things to worry about: suffering, fatigue, donation drives, and hospital bills. Back to zero. Cancer cells from the first chemo regenerated and multiplied. His body would have to go through all of the treatments again after already being so worn out by the disease. I knew he wouldn’t let its overwhelm him. Three days before the end of January, I answered his wish: “Uwi na ‘ayo ‘tay! Ayaw o na a uspi-al! Di o na aya.” (Let us go home, Tay. I don’t want to be in the hospital anymore. I can’t take it anymore.)

*

It weighed heavily on my chest.

The truth is that his mother and her relatives told me to leave the fate of Rebo in God’s hands. I remember losing my temper over their arguments. It was the most defeatist, stupid, and faint-hearted argument I had ever heard. I yelled at them. Started a quarrel. But when Rebo spoke, I stopped. Even though I wanted to continue to fight, I told the doctors to stop the treatments because his body couldn’t take it anymore. That was clear from the bruises that appeared across his body when we were just starting the first sessions of chemo.

My warrior fought for fourteen sessions and eleven months of treatment.

*

“Son, what do you want? A birthday party tomorrow? It’s in five months, ah! But all right, if that’s what you want. Yellow balloons? All yellow? Sure, I’ll buy those. We’ll prepare food because it’s your birthday! Yippee!”

On the first Saturday after he got out of chemo, he wanted to throw a party in advance of his fifth birthday. I invited many people and asked them to bring gifts. It should be the best Saturday of all Saturdays. Toys everywhere. Stuffed animals, mini-helicopters, walkie-talkies, Crush Gear, remote-controlled cars, and most of all, his favorite, the Beyblade. Lots and lots of Beyblades.

He accepted all of it and many other gifts for turning five. Even as an illusion. Even though it was not yet the time.

At the advance birthday party, he had a Beyblade tournament with his cousins.

Three days before the third Saturday, I came for a surprise visit. He was slowly losing strength. He didn’t smile often anymore. He couldn’t even move to launch the Beyblade on the floor so he held onto it in his frail hands. Sometimes he kept it in his pocket. But he tried to be strong even though he could no longer stand on his legs. He had blood clots inside his gums. Outside their home, I was very astonished when he asked, “‘Tay, may pera a?” (‘Tay, do you have any money?) I quickly pulled out my wallet, opened it, and showed him the cash crammed inside. I asked him what he wanted to buy, and he pointed to the nearby sari-sari store. No sooner had I bought the candies he asked for than he left the store and sat on the sidewalk. He was showing his fondness for me. Buying those candies was his way of showing his love for me. When we went back inside the house, ants swarmed over the untouched sweets on the pavement.

By the third Saturday, Rebo had lost all his hair. But it had not fallen out on its own. When he was irritated, he had pulled at his hair to completely remove it by the roots. On that day, I asked a favor from a colleague at work: to hire a mascot who would perform a free private show for Rebo. Though I didn’t see him smile or laugh, I knew he was happy at the end of the show. It’s the kind of happiness that slowly fades and disappears.

His strength waned in a flash, so by the fourth Saturday he couldn’t even insert the ripcord inside the Beyblade launcher. When he spoke, he felt tired and gasped for breath. I tried taking him to the carnival but he only wanted to ride the Red Baron, a small helicopter that goes up and down, and rotates around an octopus. Whenever the ride went up, he’d look at me and smile with sadness in his eyes. After the ride, he asked to go home at once. And when we arrived, he immediately went to bed and stared at the blank ceiling.

The fifth Saturday was the last Saturday of February, exactly the end of the month. And at the end of February, my son died. It was only a matter of time after his tears had fallen before his glassy eyes closed, and he breathed his last breath.

He died in my arms. They told me that he waited for me before he died. We weren’t able to talk anymore because by the time I arrived at the door, he was already screaming in agony.

He suffered for an hour and a half. Blind eyes, stiff body, mouth full of blood, and gasping breaths. “This isn’t true! I don’t believe it. My son will live! He promised us he wouldn’t leave me and his Ate Kala! Where’s the peaceful death you all told me about?!” I wanted to shout all of this to the family around me but I wasn’t able to speak. The grief was loud enough to silence me.

As someone who wanted to be a good father, when I knew he couldn’t fight it anymore, I gently kissed him and let him go. “Go ahead ‘Bo. Thank you for the four years. We love you. Goodbye.”

And I cried and cried.

*

I won’t be able to bring him to his first day of school anymore. We won’t ever have those little heart-to-heart talks between a father and a son. Or even talk over beer about dating a girl. Or even argue or debate. Or travel somewhere.

What would have been his dreams even if he only lived for four years in this world? How about Kala? They were the closest allies when the separation happened. How can I explain to my firstborn that she wouldn’t even see her brother again? That Rebo’s loss means no one will be taking her to or picking her up from school. His clothes will miss him. His shoes will miss him. His books and toys will miss him. His sister, mother, and I will yearn for him.

I forbade the Beyblades to miss him, so I put all of them inside a white bag and placed it on top of his cold, blue hands before his coffin was lowered into the ground and the earth covered his grave.

It was the sixth Saturday when Rebo left the hospital. It was the last Saturday his loved ones saw him.

The Beyblade and their owner are gone now, laid to rest in the coffin. They journey into the afterlife, where there is no sickness, no hunger, and no suffering. Peacefully gyrating and turning. Spinning endlessly in bliss.

Meanwhile, those of us left behind grieving on earth will continue to survive and learn the art of grief.