photo by a. rosé

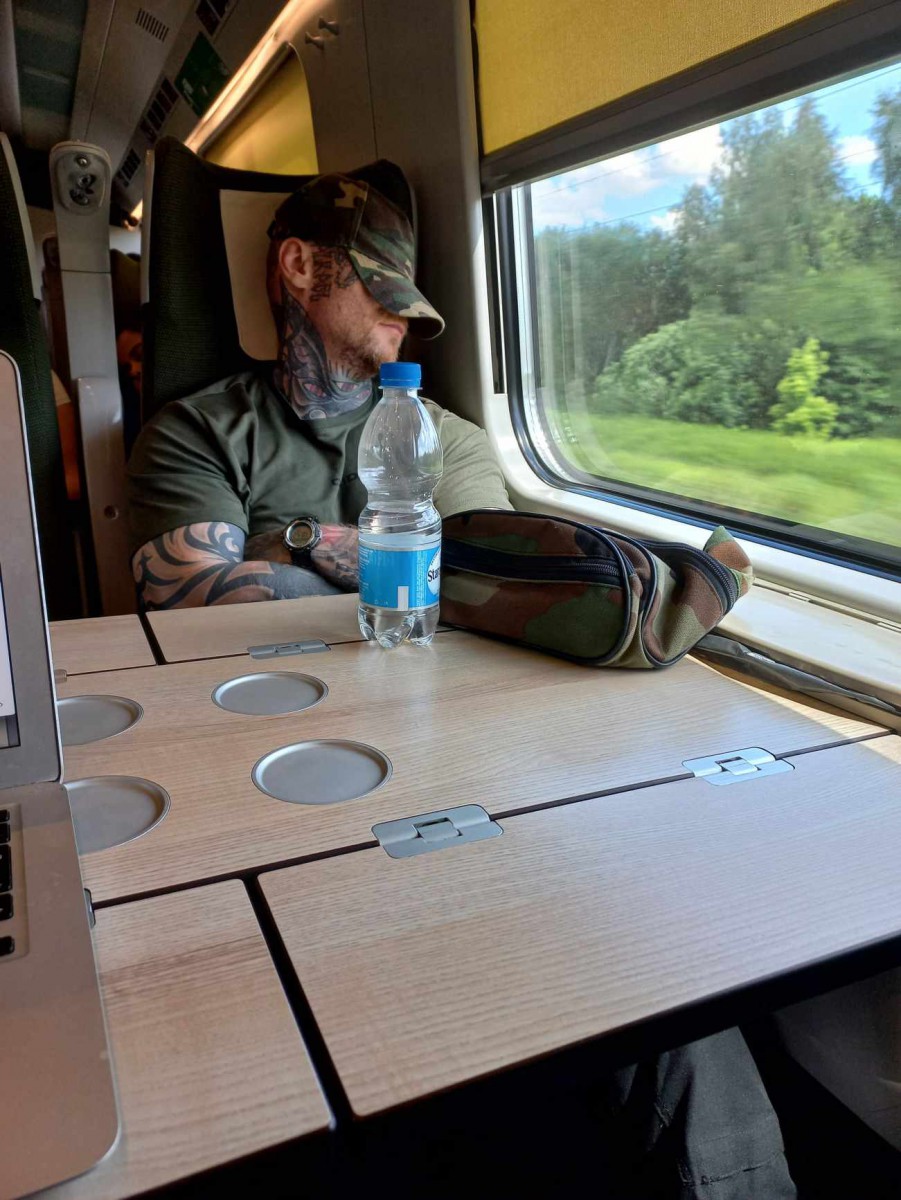

I meet a guy on a train (someday I will write a saga about the people I’ve met on trains). I ask him if the seat next to him is free. He is unable to answer. Finally he mumbles something incomprehensible in English. “Are you from Finland?” I ask. “How did you know?” “From your accent. I lived in Finland for a bit.”Tomi is returning from Kharkiv. Earlier he’d been in Severodonetsk, and earlier still near Kyiv. Immediately after the war broke out, he volunteered with the French Foreign Legion. He had fought with them earlier as well, after the invasion of Crimea.

“What’s Kharkiv like now?” I ask because my friend’s son is there. “Not good. It’s shelled. Do you know about the Wagner Group?” I nod. I am worrying about Natalia’s son, who cannot leave Kharkiv. “What about Severodonetsk?” Tomi says he has a video clip from there. He gets his iPhone and shows me footage shot by one of his friends, with soldiers moving among the ruins of houses and shooting. The Russian soldiers are so close that you can hear their responses to a legionnaire shouting “Fuck you!” at them. I look into his unbelievably blue eyes, “Did anyone close to you die?” “Yes. A friend. You know, I don’t want to fight at all. This war is horrible. It shouldn’t be like this. I met someone from Caritas, and I am thinking about returning there as a Caritas volunteer.”

I look at his lizard-like tattoos and wonder how he copes with all of this when falling asleep at night, if he sleeps at all. But Tomi is a Finn, and Finns believe in magic. He is on his way to Karelia to meet with his witch. She will heal him by drumming and singing. She cannot bleed him because his entire body is covered with scars. After that he will move on to his home in Rovaniemi where his eleven-year-old daughter lives. I see her face and her long fair hair in a photo on his phone.

Tomi has not had a drink for eleven years. Not one. He doesn’t smoke. “I have only one weakness,” he admits, and I am a little scared. “It’s chocolate,” he says, and his eyes smile. “In the army they said that I’m a bit like a woman, so delicate that all I can eat is chocolate.”

“Do you have an ideal place that you would like to live—anywhere in the world?” he asks me suddenly. “There are no perfect places in the world. I need a little civilization and a little nature, ideally. What about you?” I see he really wants to tell me about his place. “Africa.” He went there to fight. He loves the people. It’s all about people. Especially the Eritreans and the Kenyans. Wonderful people. He also was in New Caledonia because the French Legion sent him there to learn French. I think to myself that there must be no better place to learn French. It’s as if he is reading my thoughts. “It is a strange place. The islands are strange.” He learned a slightly different French than the Parisian one. Perhaps more refined . . .

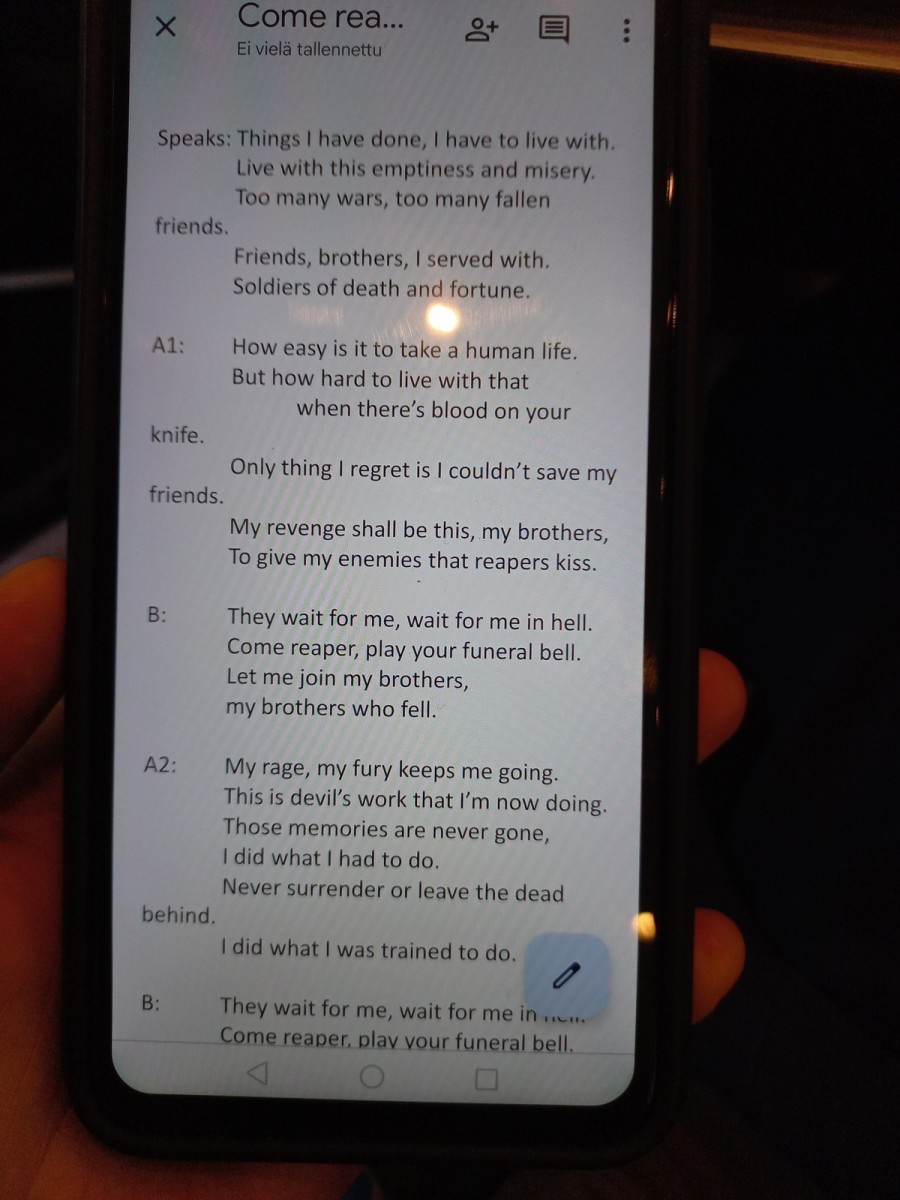

I wonder if this witch in Karelia will be enough for him. Doesn’t he need therapy? Yes, he has had therapy. And he writes poetry. He pulls out his phone and lets me read. A death metal band wrote some music to his lyrics.

I see that Tomi is tired. We exchange wishes for the end of this war. He pulls his hat over his eyes. I leave him like that when I change to my Berlin train.

photo by a. rosé

The Language of Tenderness

From my Berlin apartment I can see a chestnut tree outside my window; it drops its fruit and its leaves are being slowly eaten by time clothed in brown. In the corner store I spot Gorbachev vodka, filtered four times and crystal clear, of course. Mikhail Gorbachev died a few days ago. It was because of him that the regime collapsed, even if he tried to save it by supplying some oxygen in the form of glasnost and perestroika. Nonetheless that same Gorbachev supposedly said, “The Soviet Union without Ukraine is inconceivable” (Ukrainian Weekly, Nov. 24, 1991). The Soviet Union appeared to some as an iceberg, after the melting of which entities appeared that previously seemed not to exist, such as the Baltic countries and Ukraine. In 1989, the ‘Law on Language’ was adopted, which recognized Ukrainian as the only official language. Before that a diglossia existed that divided into a superior language, i.e. Russian, and an inferior language, i.e. Ukrainian. “The 1980s were a national rebirth,” Yuri Andrukhovych (age 63) tells me over Zoom from his Ivano-Frankivsk apartment where the air raid siren no longer sounds as often as it did. “Language was the number one topic. ‘Law on Language’ caused a big debate in society.” Yuri became active in rescuing the language as if it were an endangered species. It was necessary to create special conditions for it, new publications, and take care of the ecology of culture and the ecology of spirit. Perhaps a nation is an imagined community, as Benedict Anderson put it, yet it is difficult to regard languages as imagined entities.

illustration by a. rosé

In Berlin not a day passes without me hearing either Russian, Polish, or Turkish. Spring is in full bloom when I meet Daryna Gladun (age 31) on Viktoria-Luise Platz across from the Potemkin restaurant. This makes me feel uneasy and I promise myself never to visit this place. Daryna is dressed all in black and wears a fanny pack across her chest like a sash. She suggests going to Alexanderplatz (named after Russian Tsar Alexander I) to an exhibition of Ukrainian artists. We walk through the exhibit in the basement of a former distillery wearing masks (it’s still during Covid) and looking at the evidence of Russian crimes. Daryna tells me about them in a calm voice, like in a meditation session, as if she wanted to detach herself from what we are looking at. She escaped Bucha at the very last moment. There was no transportation anymore, and she and Lesyk Panasiuk had to walk for several kilometers. After we leave the basement I ask her how I can help her now. Does she need someone to talk to, or be silent with? No, she has already developed her ritual: she goes to the Dussmann bookstore and finds calm among the mass of books. But I can’t find calm. I start to run. I can’t stop and end up running all the way home across half of Berlin. The same day Lesyk Panasiuk sends me pictures of their apartment in Bucha, to which he returned to install new windows. Scattered shards of glass from the window panes litter the floor. They cover books and everything else like frozen snow.

I remember this a few months later when I am sitting in the Potemkin restaurant. (I won’t ever tell this to anyone. I won’t try to explain how I was caught by a big rainstorm at Viktoria-Luise Platz and went there for shelter.) I hear Russian all around me, and I feel uneasy as the rain grows heavier. I just returned from Paris, where the Indian summer was at its peak. There I sat in a Paris apartment together with Ella Yevtushenko (age 26) and Anna Malihon (age 40) after a launch event for an anthology of Ukrainian poetry published by Maison de la poésie. Two days earlier Ella was in Nancy at a hotel restaurant when an app on her phone sounded an air raid alarm. Inside the luxurious hotel, the publisher, the members of the Académie Goncourt—they all froze. Ella had forgotten to turn off the app upon leaving Kyiv. Red-haired and wearing a green flowered dress, Ella, who looks like an elf, tells me that Russian was spoken at her home because her mother was Russian. Ukrainian was Ella’s conscious choice, even if initially it was like a foreign tongue: “I had to translate everything in my head.” Still, she would read world literature in Russian, as the Ukrainian translations did not satisfy her. She calls the Russian language a colonial heritage. “To speak is to exist absolutely for the other,” wrote Frantz Fanon, who comes from Martinique. The colonizers, by depriving their subjects of language, de facto deprived them of the ability for true expression or linguistic habits, as Sartre put it, likely taken from Edward Sapir, next to the portrait of whom I was sitting recently in a cafe. “How could they, after so many years, renounce French?” wonders Isabelle Macor, the French translator of my Polish poetry, as we dine together. Sartre maintained that while trying to assimilate to the colonizer’s culture one abandons one’s own identity. “Everything had to be perceived through Russian lenses,” Natalia Trokhym tells me over the phone from sweltering Kutaisi in Georgia while picking grapes growing up the side of her house, “Everything was about giving in to Russian culture. Now it’s time to recognize ourselves.” Sitting in a black sweatshirt in Lviv in front of his computer, Ostap Slivinsky tells me something similar: “It is not that the language is innocent. It is not just a tool for communication but also of violence. In an occupied territory the signs are changed.” He cannot imagine a return of Russian to Ukraine, or Russian literature. He says that a quarantine is needed. Only then did I realize that for him now Russian is like Covid.

“Language was the means of spiritual subjugation,” wrote Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. The Kenyan author abandoned English for the Kikuyu and Swahili languages. I am talking about this with Clara Simpson, an Irish actress living in Paris. “You know,” Clara says, shaking her mop of blonde hair, “I wouldn’t claim that the English language is not aggressive towards Irish.” She remembers almost nothing of Irish. In the Introduction to his Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson asked about national identities in their relations to countries: “Anyone who has doubts about the UK's claims to such parity with the USSR should ask himself what nationality its name denotes: Great Brito-Irish?” On my way home I receive a message from Basel from Natalia Blok (age 40). Her paternal grandmother taught her in Russian. Natalia did not understand what her other grandmother and her mother were talking about in Ukrainian until she was five. I met Natalia many years ago during a writing residency in Gotland. She did not speak English then. I was the only person she could talk to in Russian, in my broken Russian. I never studied that language, but my mother read aloud to me poems by Mandelstam, Akhmatova, and Tsvetaeva in their original language. And LPs with songs by Okudzhava and Vysotsky were played around the clock. Even now I find that I sometimes unintentionally use words that are not Polish. A few months ago I asked a friend to help me carry my heavy chemodan down the stairs. He looked at me dumbfounded. So chemodan is not a Polish word . . . I did not know it was Russian. It originally came from the Persian. The BBC aired a program Chamedan on Iranian refugees. Polish walizka, on the other hand, comes from French.

Upon returning to Berlin I learn that starting tomorrow Olga Bragina (age 41) has no place to stay. Her residency is ending. I invite her and her mother to stay at my place. Irina Krasnoper, a Russian poet who has lived in Berlin for many years, brings them over by car. Olga wears a flowered coat and her white shoes sparkle with little silver sequins. She tells me that a language is not owned by any single state. “Russian is not the property of the Russian Federation,” declares Olga. I speak Russian with her mother, to which Iya Kiva shakes her head when I tell her about it later over Zoom. To Iya, Russian is a room she does not want to enter. Russian was spoken in her home. She wrote poems in both languages, but now she consciously chooses Ukrainian. “Russia and Ukraine are like a toxic relationship, and you constantly think about your ex instead of looking for someone new.”

Berlin, photo by Ilya Kaminsky

After the conversation with Iya I run to a reading by Ilya Kaminsky. He is participating in a literary festival in Berlin. After the reading we go for a walk. He tells me about his relative who, after WWII, was shot on an Odesa street for speaking Yiddish. Ilya’s poems are composed in sign language, which I do not understand but observe with fascination. In the United States, from the end of the nineteenth century to the 1960s, deaf students were beaten and forced to sit on their palms so that they wouldn’t use American Sign Language. I recall Natalia Trokhym's story from her kindergarten, where children were compelled to speak Russian. She rebelled and was forced to stay out on a balcony in December with no warm clothing for speaking Ukrainian. She stood there like a statue. “It was my war, I wanted to win it, so I didn’t cry.” She got nephritis and never returned to that kindergarten. It would be fair to say she won. Yuri Andruchovych’s kindergarten used Soviet methods; the kids were told to speak Russian, and everybody addressed each other by their last names. Once when picking Yuri up, his grandmother remarked, “All of you have Ukrainian names, why are you addressing each other in Russian?”Natalya Belchenko sends me a message; she translated one of my poems into Ukrainian. I am deeply touched. I remember our brief meeting last summer. She was returning from a short trip following the footsteps of Adam Mickiewicz, organized by the Polish Book Institute. It was very hot. Natalia wore a lightweight dress with black polka dots. She told me that in her family everybody spoke Russian. Her mother was Russian; her parents came from the villages Belomestnoe and Petropavlovka in the Belgorod region. But her grandmother was Ukrainian. She had come to Kyiv to study at the university in the 1930s and spoke only Ukrainian. “But with me she only spoke in Russian, likely so I wouldn’t have trouble,” Natalya excuses her. For the two of them, Ukrainian only showed up in songs when they sang together, as if this was a safe, neutral zone. Natalya wrote seven books in Russian and two in Ukrainian. I ask her whether Russian literature is important to her. “I devoted enough time to it to know where the present situation springs from.”

I leave for a few days: Paris, Stockholm, Bergen. I read poetry. I meet people from many countries. At a dinner after a festival in Bergen Sonia tells me where she is from. From Portugal. So I ask if her native tongue is Portuguese. “It’s complicated,” she answers and changes the topic. But I am curious about the complicated. “You see, my father comes from Cabo Verde. He spoke Crioulo. Portuguese is the colonizer’s language.” Later he moved to Portugal, where he met Sonia’s mother, and they emigrated to Holland. Dutch is her mother tongue, she says. She went to Portugal once, but her grandparents laughed because she spoke Portuguese like a child. I think about this at the Bergen airport while waiting to board, when a message from Boris Khersonsky arrives. He is waiting for a train in Ravenna. He and Ludmila are at a writing residency in Italy. They were reluctant to leave Odesa. I remember the picture of their window blocked off with books in case of an explosion—a new use for books. At his home, “Odesa Russian” was spoken—a smoothie made of Yiddish, Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian, with Bulgarian thrown in somewhere in the middle. His parents sent him to a Russian school, but from second grade they insisted that he learn Ukrainian. He wrote in “Odesa Russian.” “My Russian teacher liked my poems, and my Ukrainian teacher did not like my poems.” However, these teachers had something in common—they were not good teachers. Marianna Kiyanovska tells me, “Boris made a significant decision, and after Maidan he only writes in Ukrainian.” “But I do not renounce Russian,” he writes me.

Marianna translated Boris’s poems into Ukrainian. To do that she had to find a new language. “Odesa Ukrainian” has a different syntax and a different phonetics. She had to create a language for that translation. I meet Marianna near the Grimm-Zentrum library in Berlin. She wears a fabric necklace with a flowered folk design. At her home only Ukrainian was spoken. Her grandfather did not keep books by Russian authors, except for Blok. Marianna knows Russian literature backward and forward. Or rather from the inside, and as if from above. Chekhov and Gogol are not entirely Russian anymore. They are above this. Just like Conrad, who was a little bit Polish and a little bit Ukrainian, yet chose Africa to tell us about his heritage. This is not about Russian but about some higher language. Marianna translates from a high language, she tells me. It is not a propaganda language, or the language of political idiom, as this is a dead tongue. It is about a language where the cogito lives. Maybe it was not an accident that Marianna bought an apartment in Lviv not far from the place where Zbigniew Herbert had lived. He is one of a few Polish authors she did not translate for a long time because, as she says, she does not know how to translate irony. On the other hand, she can render a melody exquisitely, which I experience when she reads aloud her translation of Julian Tuwim’s Lokomotywa (Locomotive), and I feel as if it is in Polish. It is as if she really found this metaphysical tongue above all divisions, as Walter Benjamin put it. Above the private tongue described by Wittgenstein.

At the end of the day I walk in the Tiergarten together with my biologist friends Olivia Judson and Alexandre Courtiol, who want to show me beavers. Their sex organs are not visible, says Alexandre. You can’t tell a male from a female by sight, only by smell. Olivia is good at this. She can tell. We stand at the edge of the water sniffing. I only smell water. It is good. Olivia could tell that a pair of beavers had been there. We’re too late. Or too early. It’s hard to know. Perhaps Hegel would. I talk to a German writer about him: And here you go, Hegel and Haiti, she said, there is this book on the Haitian Revolution. About master and slave. And I think about Joseph Losey’s film The Servant, with a screenplay by Harold Pinter based on a novella by Robin Maugham, about a servant who was in fact a master. And I think how Foucault wrote about this problem, and about biopolitics. Which brings me back to my biologist friends and our discussion on heritage, on how blood relations are about power. Genetics and blood are only biopolitics. I prefer feelings. And tenderness. Expressed in any language.

P.S.

Listening On Zoom To Ija Kiva Reading a Poem About War

Yesterday we listened on Zoom as Iya Kiva

read a poem in Kyiv where the golden

caps of the orthodox churches did not run to the shelters,

we listened from our homes,

nearly everyone, listened,

and we were all eyes, as if there was

nothing else, just eyes, as if we wanted

to protect her with our eyes with which we absorbed

every word while Babi Yar burned in the background,

but memory does not burn, we trust, memory is rustproof,

memory will survive, hibernate like a mole,

all of us, a thousand people on Zoom,

two thousand eyes, wanted to hold

an umbrella of air over Iya,

shield her with our gaze,

when she finished reading, I raised my head,

on the table was a book from the library,

Emil Cioran’s La Tentation d’Exister,

the hills held Bergen in their lap,

the first crocuses were in bloom, everyone

was looking forward to spring.