The Paglota family is celebrating a significant event: the silver wedding anniversary of the central pillars of this sacred association, the family.

Since the early morning hours, the two Paglota daughters, with their curls tied up under lovely muslin bonnets, have been moving furniture and clutter from one place to another.

The spacious dining room has been transformed into a ballroom; assorted chairs, of two or three types, are pressed up against the perimeter of the room; the black accent wall, which on any given day is smudged by the white fingertips of these charming girls, shines.

One of the rooms opens to the patio, where potted plants and ferns have been carefully placed as decor; another leads to the room where lunch has been laid out. This is normally the Paglota girls’ bedroom, but their dismantled beds have been moved into the pantry.

The young ladies of the neighborhood have been talking about this happy news for fifteen days now; the announcement came out in the social notices of the parish paper. It’s expected that the event will bring together young women and men from good families.

The dresses the Paglota girls have on are new, even if the same can’t be said of their shoes, to which a heroic layer of black wax has been applied instead.

Their silk tights have also endured a little mending: a few “dropped” stitches have been skillfully repaired with a crochet needle.

They’ve spent the hour from 6 to 7 p.m. doing their hair, and it really does look elegant. The mother and father, modestly bourgeois, are wearing their best regalia.

The neighborhood patisserie has brought over a nice lunch; nothing’s missing; faces are glowing and spirits are impatient.

At around 9 p.m. the doorbell starts to ring frequently . . . girls from the neighboring street arrive, as do the little girl cousins from Flores, the Rossi family, a few boys on their own, etc. . . . Little by little the number of guests grows, the house fills with people . . .

At 10:30 p.m. we’re “au grand complet.”

In the ballroom some fifteen good-looking girls, with powdered faces and light-colored dresses, are seated in a row, chatting quietly.

In a corner near the piano, like old leaves blown aside by the wind, a few mothers have gathered, almost all of them dressed in black. Some twenty boys out on the patio smoke and talk about horses, tangos, girls, and other such things, their faces appearing somewhere between dull and childlike.

Among the girls present, four or five play the piano, and one of them starts things off with a lively tango that electrifies the legs of the patio boys as if they were running on Volta batteries.

The girls gaze provocatively towards the door that leads to the patio . . . six or seven faces peer in, but the attraction isn’t sufficient yet to mobilize them, and the tango proceeds, coming to an end without being danced.

After some brief chatter, new introductions are made, a few more people come in, and the same girl makes the piano bounce to the rhythm of a foxtrot.

This time, the Paglota boy chooses a partner and the dancing gets underway. By the third song, there are already three or four couples on the dancefloor, and by 11.30 p.m, the ballroom can no longer contain them all, and a few people go out onto the patio.

The girls take turns dancing to the upbeat pieces, which are mainly tangos, two-steps, foxtrots and a few Boston waltzes.

The majority of those present dance skillfully; from time to time one might notice a boy attempting to enliven his cumbersome and awkward partner, or another who, despite his best efforts to the contrary, gives himself away as a cabaret regular.

If you’ve seen one boy, and you’ve seen them all; uniformity defines them . . .

It’s that same shiny hair slicked-back with greasy products; it’s the same tie, the same figure, the same conversation, the same ideas.

Are they the sons, perhaps, of a hole puncher that suddenly pops them out of life and throws them into the middle of family dances?

The girls, at least, each have their own little personalities . . . This one here has a nice smile; that one over there plays the piano well, another has an alluring head of blonde hair; one’s first impression is that they’re all coming out of individual cocoons . . .

We’re left wondering how to account for this difference, since they are from the same homes, have the same education, the same traditions . . .

The answer is simple: an 18-year-old woman is already a woman; a man of this age is an insubstantial thing, and doesn't even have what women instinctively possess: grace.

Once again we’re back to following the dancers, tireless, rhythmic, heroic. At about 12.30 a.m. everyone moves on to lunch.

That’s where the boys get some real personality . . . and it sometimes happens that a girl loses hers.

Two more hours of dancing, and a comforting and well-timed hot chocolate.

Later, more tango, two-step, foxtrot, the cumbersome girl, the boy who almost suffocates his partner. The eyelids of the serious ladies in black begin to droop; a few at first, then others, begin the rush to leave.

But there are still eight or ten couples that don’t show any sign of giving in to tiredness . . . At 6 a.m. the ballroom is empty.

Chairs in disarray, the piano open, a few flowers fallen on the floor . . .

A smell floats in the air, with hints of powders, perfume, makeup, brilliantine, people of the white race . . .

The girls dream strange dreams; the boys discuss the particulars. Nothing.

An honest family dance.

Certain poems by women tend to be more dangerous than this . . .

Artwork by Hugo Muecke

The Irreproachable WomanI have a particular fondness for the woman who goes out-and-about, irreproachably put together. From her fine complexion and the sweet glint of her eyes to the tiniest detail of her handbag, she provides a pleasant resting place for the eyes of the passersby.

The truth is that life is quite complex and varied, and therefore everyone has the right to interpret charity in their own way.

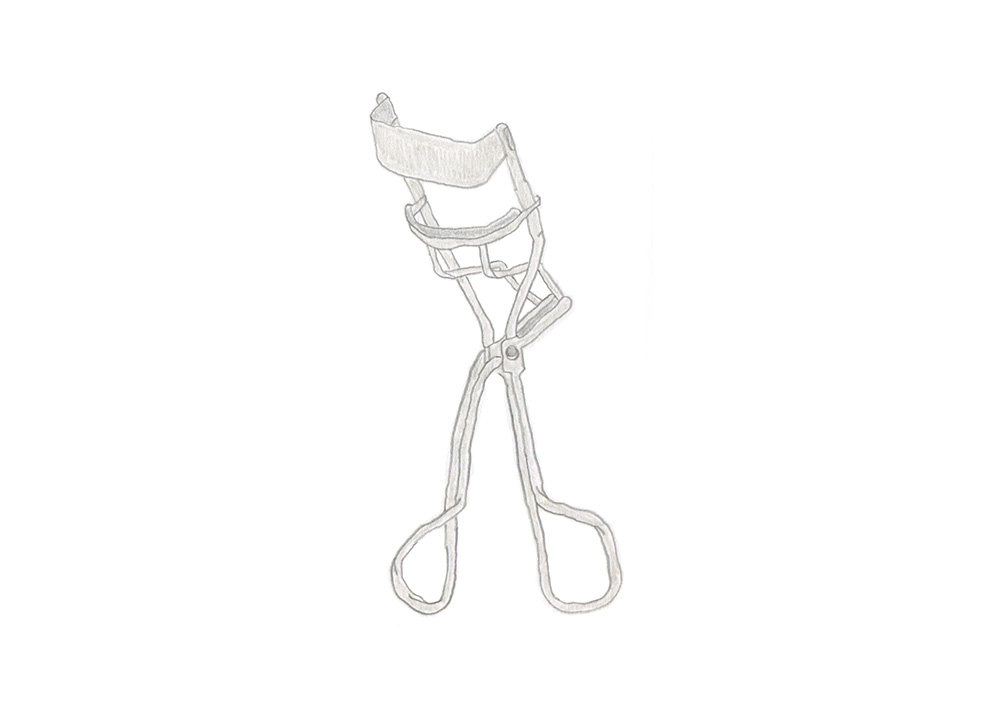

Without a doubt, the benefactresses of humanity are those skillful little ladies who spend half an hour in front of the mirror for no other reason than to curl their eyelashes and arch them away from the eyeball, correcting thus the handiwork, most likely of a left-hand, that shortened by half a milliliter the ellipse of her ocular orbits.

And obviously it would be cruel, aesthetically speaking, not to forcefully obtain that extra half a millimeter, or less, that well-arched eyelashes are able to induce thanks to an optical phenomenon.

Furthermore, because there aren’t any forests in Buenos Aires, if we discount those in Palermo, which are very remote, and those that appear on postcards and paintings in shop windows, and that, it goes without saying, don’t move no matter how hard the wind blows, those benefactresses have surely thought about how charitable it is to provide the gaze of the passersby with the happy spectacle of a dense jungle of large lashes, in the center of which two blue, green or gray lagoons complete the illusion of bountiful nature.

To achieve this result, the oils of walnuts, almonds, castor and many others flood the root of each lash overnight, like irrigation ditches that, when overflowing, flood the roots of each tree and fertilize a favorable plot of land for a new tree (or a new lash).

By repeating this procedure for months on end, an increase of eight lashes per eye is achieved, as well as considerable growth of the little lash tree itself, if my friend’s calculation is to be trusted.

Other equally well-known routines in the care of nails, skin, hair, cheeks, undergarments and outerwear, mean the irreproachable woman needs a lot of time before she can leave the house all made up, whether to go shopping or for tea or simply to show off her newest dress.

Observe her way of walking, such a discreet and modest stride! If you were to measure it, you'd find that it does not exceed 30 centimeters. The head, so very elegant, forms a slightly obtuse angle of 105 degrees (an invariable) with respect to the neck; she has the look of a somnambulist, her mouth is inscrutable; the jungle of her eyes triumphant…

The cut of the dress is irreproachable: the shoes—with such fine material—contour the toes, true to their form; the tights reveal a mother-of-pearl pink; the hat adjusts to the head like to a mold; the gloves, tantalizing the fingers, are only separated from them by an imperceptible layer of air; she seems, all in all, to have just stepped out of a wax bath.

If you see her at 4 p.m., when she leaves her house, and come across her again at 7 p.m., when she returns, you’ll observe that not a single hair is out of place, and that the doorstep that saw her off in all her perfect radiance welcomes her back in without any aesthetic percentage discounted.

I have here a statistic that a friend gave me; it’s calculated based on three to four hours of being out-and-about, including visits to shops and tea houses.

Approximate movements required to maintain irreproachability while out-and-about:

Glances in the mirror (different types, sizes and reflective surfaces) — 25

Glances in shop window panes — 60

Stretching of gloves — 12

Adjusting of pins so that they don’t fall out of place — 10

Moistening of lips — 30

Special emphasis of the bosom with a slight pulse — 5

Lifting of the hands to the hairpins that keep the veil in place — 18

Touching up of powder (very discreetly) — 2

Straightening of the seams of tights — 2

Furtive polishing of shoes, by rubbing them against the back of the leg — 6

Unanticipated adjustments of handbag, collars, folds etc. — 50

Total movements — 220

Assuming these tactics for the maintenance of out-and-about irreproachability are kept up for two years, at two outings per week, and that this aesthetic fervor lands the prize of a husband, we surmise that this husband would represent around 45,000 such “ad-hoc” movements. This muscular wear and tear alone, not to mention the corresponding accumulation of toxins, would be enough to awaken the zeal of any moralizing hygienist. “N’est pas.”

And after all that, let anyone dare claim that a man isn't worth anything . . .