I begin with these hypotheticals, at risk of sounding gimmicky, in hopes of conveying how much Robin Moger—one of the most prominent, and deservedly well-regarded, translators of contemporary and classical Arabic literature at work today—has taught me about translation as a creative act. Whoever the novelist, poet or essayist he is rendering into English, every text of his is suffused with a supple sensitivity to the vagaries and contingencies of style, a virtuosic grasp of how each semicolon dotted, each sentence broken off, each space held open for a poetic line might breathe a necessary air into the chambers and vestibules of the writing. When I read Moger, what comes to the fore, surely as a photograph being developed, is the sharp silhouette of a writer’s singular voice—whether that be sheathed in Iman Mersal’s laconic, dust-flecked perambulations, Haytham El Wardany’s starkly alchemised aphorisms, Mohamed Kheir’s dream-like landscapes of ruin, Youssef Rakha’s fitful fragments, or Wadih Saadeh’s fugitive metaphysical transits.

Nor is his range restricted to the modern. From pre-Islamic poets like Dhu al-Rumma to Sufi mystics like Al-Niffari, the ancients have also received their fair share of attention across Moger’s career. Noteworthy is the fact that his translations of the premodern corpus almost always experiment with form and movement; out of well-worn palimpsests are created texts afresh, as if greeting the daylight for the first time. They feel wholly new, a staging ground in which the avant-garde bends over to encounter the enigmas and silences of the aged. Pursued to its logical conclusion, this backward-looking gaze culminated in his transcendent collaboration with Yasmine Seale, Agitated Air (Tenement Press, 2022), where each took turns translating and rewriting the same Ibn Arabi poems across numerous versions and iterations. From one poem that plays on the conceit of the doubled letter in Arabic, Moger re-enacts the painful vacillations between splitting and merging through the formal and acoustic duplications of his translation—the “doubled sign” whispering to “doubled figures”, the internal rhyme of “my slightness and your light”, not to mention the poem’s very division into two columns before its final coalescence. These are missives saturated with yearning, testaments to the insatiability of desire and of writing.

In Moger’s hands, every writer’s idiolect feels carefully wrought, invented for its purpose, distinct in its shades and tonalities. I think of Virginia Woolf’s musings on style in a letter to Vita Sackville-West: “Style is a very simple matter; it is all rhythm . . . A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it, and in writing one has to recapture this.” One doesn’t need to know Arabic to sense this ineffable pulse, but comparison with the original language is always revealing; often, Moger takes liberties with the surge and ebb of syntax and diction, omitting and embellishing alike in service of a more expansive pattern. His English prose, honed from these rhythms, sometimes contorts and stretches to accommodate what Arabic sounds like, as in this sentence from Golan Haji’s “The Names of Love”: “He nothinged Moses so that love might begin from nothing.” As one might fathom, the words rendered as “nothinged” and “nothing” derive from the same trilateral root in Arabic. But if one were to probe further, one would see that this root itself—لشى or lam-shin-ya, with the sense of “annihilating” or “crushing”—is itself a composite of two Arabic words, la and shay, meaning “no” and “thing”.

Much hinges, too, on seemingly minute but crucial structural decisions that colour the texture of an entire work. In El Wardany’s The Book of Sleep (Seagull Books, 2020), for example, Moger opts to do away with the definite article for particular operative nouns, shrouding words in an aura of elemental gravity: “Night follows day like its shadow. Day runs, to escape it.” And later on: “Dream is only complete when it is noticed subsequently, just a half turn of regard after which it dissolves into reality and blends with other states.” Almost imbued with the status of sentience, these lithe figures prop up the distilled axioms that pervade El Wardany’s meditations. I’m reminded of what Don Mee Choi does with the word “Bird” in her translation of Kim Hyesoon’s Phantom Pain Wings (New Directions, 2023), reiterating it like a talismanic name until it floats on the brink of intelligibility.

Even on the level of the individual word, Moger reveals an acuity that springs from years of experience and erudition. To cite a favourite instance of mine: “Enayat becomes an archetype, the figure he gestures to whenever he wants to discuss women’s writing, or suicide, or murder, or any of the strange and marvellous things he may have witnessed in the course of his life”. This is an innocuous sentence on the surface, taken from his translation of Iman Mersal’s Traces of Enayat (And Other Stories, 2023). But braided into the ingenious phrase “strange and marvellous things”, which accordions out from the single word ghara’ib (from the root meaning “obscure” or “strange”) in Arabic, is Moger’s recognition of its frequent usage in tandem with ‘ajab, or “wonder”, in the Arabic textual tradition. An affective topos associated with the obligation to marvel at God’s sublime creation, the invisible ‘ajab in Mersal’s writing is shorn of its devotional inflections and resignified, instead, with the predatory gaze of the male critic who co-opts its objects only to aggrandise his own ego. Through the subtle addition of “marvellous”, Moger conjures a boundless semantic universe—at once “claustrophobic and infinite”, as he himself says, in its mirrored reverberations—into being.

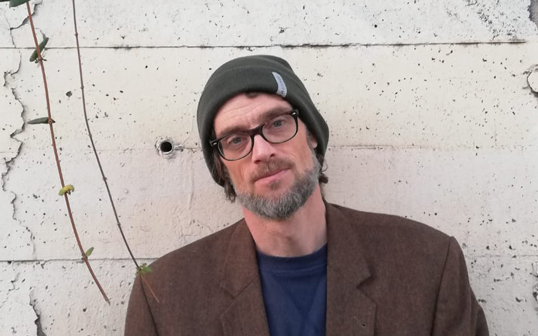

I dwell on these texts at such length because I suspect, from our months-long correspondence, that Moger himself would like for the writing to be foremost; all else, like biography, is so much dross. Yet no account of the translator would be complete without at least a sketch of his life.

After graduating from Oxford in 2001 with degrees in Egyptology and Arabic, he lived in Egypt, where he worked for several years as a journalist at The Cairo Times until its closure. In 2008, he moved to Cape Town. Professional translation had already become a vocation for him by then; after a smattering of shorter pieces in journals and newspapers, his first full-length translations of novels by Ahmed Mourad (Vertigo) and Hamdi Abu Golayyel (A Dog with No Tail) appeared with the American University in Cairo Press in 2010. In parallel, he ran a website entitled Qisasukhra (“other stories” in Arabic) from 2012 to 2018, posting occasional experiments in translation that would often go on to evolve into close friendships with writers and full-fledged translations in print. Since 2021, he’s been residing in the city of L’Hospitalet de Llobregat in Catalunya.

Over the years, Moger has garnered numerous accolades like the Saif Ghobal Banipal Prize for his translations of Yasser Abdellatif’s The Book of Safety (AUC Press, 2017) and Kheir’s Slipping (Two Lines Press, 2021), as well as the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for Mersal’s Traces of Enayat. These prizes, unsurprisingly, belie Moger’s own ambivalence about the fraught reception of Arabic literature in the Anglophone world, its tendency to be reduced to the status of anthropological or political documents. Indeed, he nearly demurred when I first approached him with the prospect of this correspondence, citing the underuse of his “discuss-my-process muscle”.

For all that, I am delighted and honoured that he eventually agreed to speak with me and to entertain my garrulous questions about such illimitable themes as space, desire, otherness, and the ancestral. We began speaking in September 2024 and wrapped up our conversation in January 2025—an ending that feels only provisional, as is often the case with the best of interlocutors.

—Alex Tan, Assistant Managing Editor

By now, you’ve built up quite an extensive and awe-inspiring body of work in translation. I’m most familiar with your more recent publications, including Mohamed Kheir’s Slipping, Haytham El Wardany’s The Book of Sleep, and several books by Iman Mersal (Traces of Enayat, Archives and Crimes, How to Mend). All three are Egyptian writers; they’re quite self-consciously literary, often genre-bending and aesthetically innovative. How have you, over the years, acquainted yourself with the contemporary Arabic (or Egyptian) literary scene and the places that different figures occupy within it? What sort of trajectory did you chart through the Arabic language and into literary translation?

The books you’ve mentioned are the most recent ones I’ve done, though in the case of all three authors I’ve been reading them and translating their texts for quite a long time. When you ask me how I came to where I am now and the way that I work, my initial reaction is to draw a blank. I think that’s because I don’t feel that my progress is best represented as a trajectory. Instead of a smoothly arcing arrow, it feels more to me as having been a learning process conducted against circumstance: picture a pinball machine.

I didn’t start out understanding this, but I now think of translation as being a way to read and grow as a reader, and learning to fix that reading as writing; to think about language and literature and to practice it. From inside this process, literary translation as a distinct practice is not really meaningful beyond being a site where, potentially, you would be able to translate with maximum deliberation and purpose. It’s relatively recently that I’ve been able to work principally as a literary translator and to have greater freedom to try and bring texts that I am interested in to publication, texts that might in some way represent my own project as a reader, my engagement with the literature.

Really, the pinball (or otherwise fungal) course of my career as a translator has been determined by reading, being in contact with writers through that reading, and then through what those conversations and readings throw up. Quite a lot of what I discover is through using translation to read texts, experimental translations that allow me to feel my way into the writing and see it. For a while I had a website where I published those scraps and tests that I thought worked, and that put me in contact with a lot of writers and helped maintain contact with others. There’s a sort of reservoir of projects-in-formation that I try to come back to when time and opportunity allow.

Perhaps, too, it gives you a degree of immunity against thinking about texts in the terms you might be required to sell them with, when you have the opportunity to work from inside your own reading. It also lets you grow into a landscape without feeling the need to map it from above, exclusively through models that come from outside it, or try to pressure it into shapes that rob the work of its purposes.

All of which is to say that ideas like “trajectory” and “scene” are complicated, because whatever constellations of writers I read are held together as much by my own, often very personal logics—ones they themselves don’t have to subscribe to.

Thank you for this beautiful, measured response; through it I feel like I can trace the lineaments and movements of your thought. Your website Qisasukhra is where I discovered Iman Mersal for the first time—I continue to turn to that essay on Saniya Salih. Now I see how the site has functioned as a kind of readerly archive of names that I recognise first of all in your translation, in your voice.

I want to ask if you could unpick a little those personal logics you’ve alluded to, by which you’ve constellated an education—a life in reading and writing. When I read your translation of El Wardany’s The Book of Sleep shortly after I finished Kheir’s Slipping, I was struck by the continuities I intuited between them: the oneiric cartographies that each, in his own way, sketched. Or perhaps even between Iman Mersal and Osama Al Danasouri, whose work you’ve translated for qisasukhra—I know they were comrades, loosely of the same generation, and that she memorialised him in her poetry. When you look back on the darting of the pinball, do you retrospectively glimpse flashes of affinity that might not have been as apparent at the time?

It’s helpful that you mention “my voice” because, though a problematic element on some level, it helps talk about the affinities between different writers’ work—not because it is the link, at least I’d hope not, but because what happens to my voice is a marker of how I’m reading and thinking about the text. This, in turn, is often determined by how I have encountered the text: its literary-social context, for want of a better phrase—that it mirrors connections that exist between the writing of different authors, but also the connections that I have drawn between them, which may be assumptions and approaches contingent on the how-and-when of the moment I read it.

The boundaries between these things are blurred, though, or a matter of perspective. You mentioned Osama El Danasouri and Iman, but I first started reading Osama after talking to Yasser Abdellatif, and Hamdi Abu Golayyel, who were friends with him. Hamdi Abu Golayyel, who recently passed away, was a writer I started to read after an afternoon visit to the Merit offices and the Madbouli bookshop in Cairo, from which I brought back his novel (which I later translated as A Dog With No Tail) and another novel and story collection by Muhammed Mustajab. From that moment the two were very closely associated in my mind—a mordant humour and a horizon so black the only visible relief is the writing itself. It was only later, when I translated Hamdi’s novel, that he told me how close they had been in life, but insisted his writing was nothing like Mustajab’s. And he was right, because Mustajab’s world of rural violence and human failure is dressed in a baroque, parodic formal Arabic, while Hamdi’s storytelling is transparent, stripped and broken—but even so, sometimes they seem like two sides of the same coin, the same characters speaking. I sort of unlearned my earlier sentimental reading in the end, but even now, the way I translate Hamdi’s writing is informed by that first association, one that I argued about with him until he passed away. And that affective grouping has expanded to include other writers like Nael Eltoukhy. To wrap up the point, I feel—and sometimes worry—that my writing of these texts starts to reproduce phrasing and strategies simply due to those affective associations.

I suppose what I’m describing, in an overly Byzantine way, is just what happens when you read. Perhaps more usefully restated, it is not only that patterns do exist, in the sense that connections between texts and writers start to be revealed in hindsight, it is that somehow, inevitably, the cumulative effect of reading and working in translation is that the experience becomes you. This image is essentially one of limitation, but then from that shape grow more branches. Which is something that Iman’s writing is often about: shaping reading and having the reading shape you and the text; agency is muddled, though it’s always your hand that writes in the end.

What would you say you’ve been drawn to—whether stylistically, thematically, or otherwise—in another’s writerly sensibility or world?

What attracts me in texts that I translate is the existence of space in the text. That could be in a number of ways, such as, texts that feel fragmentary, or collage-like, most obviously things like The Book of Sleep or Slipping, but also Youssef Rakha’s series of novels that begins with The Crocodiles. Perhaps the most extreme practitioner of that is Hamdi Abu Golayyel, where the fragmentation/collage is extremely patchy and jagged-edged and permeates right down to the level of the sentence, with its sort of shrapnel, stop-start, highly simplified diction. Then, as with Hamdi, it can be in the writing; or, as with Eltoukhy and Mustajab, simply in the deployment of ironic modes and the tensions this produces. I’m currently translating a lot of prose by Golan Haji, a series of pieces about many things—artists and travels and childhood—through which lines of thought surface and begin to tangle. And of course, and still speaking very generally, this is what poetry offers. It is to these spaces, sometimes perilously, that your affective, supratextual, cumulative understandings are drawn as a reader. As a translator, they are fascinating because the space itself must be maintained and not glossed—you are reproducing the effect.

In other words, such moments are participatory and not didactic—though of course they are precise and rigorous, too. Participation isn’t the same as bringing yourself into the text, although that happens, but rather a demand that you really think and care. The other thing in translation that is important to me increasingly is to try and work on texts that wouldn’t automatically be sought by the English-language publishing industry, or that don’t submit to certain kinds of prêt-à-porter readability it naturally enjoins. Publishing clearly hasn’t worked out how to think about Arabic literatures and I like to think that this is a good thing.

I feel so moved reading your characterisations of each writer’s style: the “black” horizon, the “collage-like” textures, the “shrapnel” diction. You’ve preempted something I had wanted to ask you very early on, when I had first imagined speaking to you; whether you assign a kind of visual image to the sensibilities of the authors you’ve worked with.

I was rereading The Crocodiles, and I think this time I was really bowled over by the density of the literary history, the insider’s knowledge that Rakha and his narratorial persona command over the landscape of contemporary writing in Cairo, the moving ways in which he then relates these amorphous group formations to something like generational affective investments and disillusionments, across epochal historical events. And there’s the whole quasi-roman à clef conceit, if one can call it that, coexisting with true-to-life figures appearing as themselves (Sargon Boulos, Nael Eltoukhy, Wadih Saadeh . . . such refractions, and foreshadowings); I love how Haytham El Wardany’s The Incomplete Literature Group is cited as an epigraph and resurfaces, later, under the pseudonym Saqr Al Janaini (if I’m not mistaken), within the diegesis. And I suppose Radwa Adel must be Arwa Salih, whose The Stillborn is transmuted, when dissolved into Rakha’s fiction, into The Prematures.

You brought up the existence of space within a text. I want to pick up on this thread, in relation to the literary self- or meta-theorisations that come up in Rakha’s The Crocodiles. For one, there is the notion of endless, perpetual incompletion, which seems to bear some kinship with what you’ve called “space”. In this view, unity might ultimately be an artifice and falsehood, serving only to shore up the ego of the authorial persona at the work’s heart. Instead, ceding to the unfinished nature of the work means accepting that which is “perpetually moving and transforming”. And then, much later on in Rakha’s text, the narrator Youssef puts forth a tentative philosophy of the poem as akin to love and the mutuality of desire that it brings. Both poetry and love are united, in this reckoning, by the ephemerality of the joy that each occasions: “If there be such a thing as poetry, then that thing is, to be exact, the joy of a poem’s arrival.” When I read this again, I thought about your word, “space”—the space, perhaps, antecedent to and necessary for such an arrival. A temporal clearing, perhaps.

Between these two approaches to the “space” of the literary (as I understand them), I’m curious about the extent to which they align with, or depart from, the way you’ve thought about writing, and translation. You’ve translated a significant amount of poetry, too, something which is thematised in The Crocodiles through the numerous iterations that Nayf produces of the central Allen Ginsberg piece. How does “space” inform delineations between genres, or between prose and poetry, in your mind? If any generalisation is possible here, across what unit of meaning—the sentence, the paragraph, the individual word—do you tend to bridge (or to maintain) the space between the text and yourself?

The spaces that interest me most are the ones that immediately open up when you start to write a translation, to add to those that exist between the original text “on the page” and whatever it is—once read—“in your head”. I find immediately that that text begins to change, because your translation has trajectories that tug and pull at your first reading. The potentiality of a reading, which is a sort of swimminess of imagery just the other side of being concrete, and things like the sound of its voice and pitch, even the way you emotionally respond to what is happening in the text—you are forcing these things to be less fluid. Essentially, you have to remake that potential: not just mirror some of the voices and registers you heard in your reading, but make them accessible to your reader, in turn. Over the course of longer texts, I sometimes find myself trapped by earlier decisions, which have sort of knocked the text off-course—foreclosed its potential.

Prose fiction is denser; there’s less space to go wrong, for instance, but the decisions also have to be taken more immediately and holistically, with regard to the nature of the text. Poetry decisions often feel different in nature. They are more about the potentiality of the text and precision with space; the most important choice is about retaining difficulty and ambiguity, and resisting strategies that neaten or consolidate meaning and imagery. One difference, at least as I express it to myself, is that prose often actively demands aestheticisation—which here I think of as a kind of persuasiveness or conviction acquired from internal consistency and harmony, a sense that the text is meant to be the way it sounds. In the reception of a translation, there is an irony that aestheticisation in prose, if done strongly, is often glossed as “poetic”. To describe it another way, this is about allowing the various strategies of the author to register as intentional. This can also be true in poetry, because there may be a use of imagery or meter or other references that direct the reader to a literary and cultural heritage, which echo must somehow be made evident, even just the fact of it. But otherwise, the work is to allow disjuncture and unfamiliarity, or plainness.

In The Crocodiles you find another layer to this problem, which is the use of texts within texts, where the reading of the embedded text is already predetermined by its function within the wider narrative. Indeed, leaving aside the constantly re-worked Arabic versions of Ginsberg, there are many poems by writers such as Mohab Nasr and Ahmad Yamani which are used to illustrate a point and—which is important—have been subtly rewritten by Rakha, or even simply misremembered, in a way that makes them part of the novel’s world, placing them in the narrator’s control and serving his purposes. This is a beautiful commentary on reading and transposition, which is appropriate in The Crocodiles, whose lineage runs back through Bolaño’s Los detectives salvajes to Cervantes: characters that make their lives out of/into texts.

I have translated an essay by Haytham El Wardany on reading and writing that uses various poems as texts whose vocabulary is mined to provide branching etymological trees. Golan Haji often does the same, most recently in an essay about love, which discusses the incident in the Sinai desert, when God explodes a mountain into dust before Moses: the Qu’ranic texts in the piece have to be translated in a way that links with Ibn Arabi’s use of various words and the text of the piece as a whole, pulling them away from standard English versions of the Qu’ran.

Finally, I’m reminded of a brief project I had translating two poems—one by Dhu al-Rumma, the other by Al-Nabigha al-Dhubyani—in which the poems are annotated with the akhbar of the poets: the semi-mythical reports of their lives and adventures that often provide biographical “explanations” of why the poem was written and thus what it might mean. By placing a translation in the middle of this cloud of information that tries to defy its biographical gravity, I wanted to reopen spaces in the poem which, it seems to me, cannot be reduced to the intentions and purposes traditionally ascribed to it. To sort of recreate a mystery. At least, to see what that might look like.

You seem to be pointing to an alterity opened up or enabled within the space of the poetic, an elusiveness in the way a poem might turn and branch out, which you strive to make room for in translation. And yet, you’ve also brought up densely palimpsestic texts that you’ve worked on—they embed themselves within recursive citational networks, and often stage the act of reading in parallel to making a life. Individual words, motifs, tropes can reverberate with the undertone of tradition. Perhaps these referential intensities are heightened in the case of Arabic, given the thick continuities that have extended from its classical corpus into the present, so that works from centuries ago continue to be intelligible to—or float within the consciousness of—a contemporary Arabophone readership.

In a similar vein, I’m thinking of the recycling of conventional language in many classical Arabic genres—like the bemoaning of fate’s caprices, or glory’s transitoriness, in the city elegy. Or, perhaps more elementally, the topos of the atlal or the ruin, the grief over the traces of the beloved, that runs all the way back into pre-Islamic poetry. I see this present in the Dhu al-Rumma poem you translated: “these traces which / live out your absence faded / like the tattoos on their arms . . .” It makes me wonder about the threshold at which a particular linguistic constellation shades into something we can call “cliché”. But also: where it seems to have pejorative connotations of derivativeness in English, it feels more like a mark of recognition and erudition in Arabic.

In view of this push-and-pull between poetry’s otherness and its recourse to an already-existing stock of genre conventions, how do you relate to the ancestral and the ghostly imprints it leaves on the Arabic literary tradition?

I’m not sure I think that cliché is really the way to look at it. What might be clichéd is the secondary writing/scholarship about something like the atlal, or anything that simply reproduces certain tropes as a kind of technical achievement. Otherwise, I just think of it as referencing, which of course can be done badly. But anyway, I think the cultural weight given to the phenomena you’re talking about can be overstated, especially when they’re assumed to be central to Arabic poetry, when in reality traditional forms and approaches occupy quite a marginal place in contemporary Arabic poetry. Or rather, an overly fetishistic approach to those traditions—kind of like the spectrum of approaches to the sonnet in English. What should it be, to be a sonnet? And what does writing a “good” sonnet involve?

Though the Dhu al-Rumma poem has much that is classical about it, what it shares with the al-Nabigha al-Dhubyani poem (that I translated the same way) is a certain strangeness—potentially because they are later composites or redactions of part-poems, or because their content and imagery seems to be too much for the purposes attributed to them. They are rich enough to let the bacteria of my translations breed on them, refusing the glosses offered by the tradition and perhaps uncovering something hidden and true in them, accidentally. Passionate accidents.

I’m reminded of Agitated Air, your correspondence in poems with Yasmine Seale, and how you both would translate and re-translate the same Ibn Arabi poem multiple times, almost enacting a circumambulatory movement in a language of burnished intimacy.

What desire pulsates beneath the epistolary reinscriptions you’ve both undertaken, between repetition and newness, when a sentiment or a gesture is rendered numerous ways? And why Ibn Arabi? Sometimes reading Agitated Air feels like watching a thread fraying, unravelling. Just to take one moment out of context: From “The breeze may lie, may sound out sounds unmade.” to “And the wind can lie when it makes strains / of nothing.” and later “I recall the false winds coming in / With airs. Singing themselves”. How diaphanous language itself seems in these iterations, shimmering with its own airs and lies. The Arabic and the English, your two versions refracting one another.

Though Agitated Air brings a stronger purpose to the texts of Ibn Arabi, the mechanism seems similar to me. All the conceits—the correspondence, the arc of a relationship, the bending of the poem’s language and form—are suggestions that arise from the poems themselves and the possibilities offered by their fractures and imagery. Nothing escapes the originals, but is written around them, and couldn’t be without them. At no point did Yasmine or I, I think, ever feel that there was any end to the possibilities of the form, though your image of refracted work rings true, because there is a cumulative determining gravity that starts to shape pathways between the Arabic poems, the translations, and the two translations. To some extent, the last stage of the book, the arrangement of what I sometimes think of as the relationship arc, obscures this particular chronology of creation.

In her book The Arabic Prose Poem, Huda Fakhreddine wrote about Golan Haji’s work with the British poet Stephen Watts. They produced English “translations” of Golan’s poems together that were essentially rewritings, and Fakhreddine says, “The Arabic is not an original; it is only a previous translation of poems ‘imagined’ multilingually. In their English iterations, the poems are Haji’s as much as in the Arabic. For this reason, I did not attempt my own translations of Haji’s Arabic poems.”

I definitely am not offering this as a sort of manifesto for translation in general, but I do think it’s true that your translation grows out of the original somehow, but not necessarily directly: a totally different object (or shape) that must nevertheless be recognisable as the original’s twin. A rock and a flower, but when you lick the rock and chew the petals, both taste of oranges. The degree to which their (real) causal relationship is recognisable or foregrounded depends on the context of its publication: in some contexts, it is of paramount importance because it is the translation’s purpose, its legitimacy. In other contexts you can risk that legitimacy in hope of finding treasure. Nevertheless, in all my translations there are these moments when I recognise that I’ve found something with a particular phrase or rewording: something like the voice you need, or the path to it, or more vaguely—but no less forcefully felt—some idea of how.

I suppose I used “cliché” imprecisely, and perhaps with the misguided intention of reclaiming for it some positive meaning—what I wanted was partly to surface the richness of quotation and intertextual reference as an unremarkable structural feature in classical works of adab, and to mark in some way the muddied, troubled boundaries of the concept of authorship. If we were to shift attention away from the content of repeated motifs and images toward something more like a repertoire of formal principles—techniques of reading, as you pointed out—I’d be curious to ask you how, if at all, these interpretive methods have shaped your own approach to translating Arabic texts. To what extent, and in what ways, does etymology bear on the decisions you make? Is this related at all to your refusal of the “glosses offered by the tradition”, when you translated Dhu al-Rumma, to subsequently uncover “something hidden and true in them, accidentally”? If you could elaborate a little on this circumventing of the tradition’s glosses, I’d be grateful!

There are two ways to look at the tradition’s commentary on these poems. First of all, you have the commentary that is more or less strictly linguistic and grammatical, that explains what the poet meant by this word or phrase, who the subject of the verb is in this confusing line. In the case of these commentaries, not only did I not circumvent them, but I also couldn’t have produced any translations in the first place without them, because in the case of the poems and poets I chose, they might be the only way to understand some things.

But on the other hand, the contextual commentary, the commentary that places the poem in a particular narrative and as the product of a particular set of circumstances—an urge that seems to come in some cases from the need to explain the poem’s strangeness, and to reconfigure the tradition as a single evolutionary line—is the one that is being put under strain. It should be said that this contextual stuff often affects the grammatical parsing of the lines, so in some sense it’s a closed loop. It’s also not particularly original to do that, but the real idea is to sort of maintain this awareness that you, as a modern reader, and perhaps as someone not raised with the slightest awareness of that tradition, exist at a distance in spacetime from everything equally—both the tradition and the lost context it effaces. Yet you cannot, in the act of translation, avoid remaking the poem inside the bubble of your own context—a new coherence arising out of your tradition (which may be more incoherent, or seek incoherence, but which is a tradition nonetheless). In other words, your quest is to seek gold, and the ancient poem, in its translation, is perhaps the way you make breaches to let it be seen beneath the blank rock wall.

In “To the Dead, To Those As Yet Unborn”, the essay you recently translated, Haytham El Wardany brilliantly uses Arabic grammar and lexicography as an elemental metaphor to elaborate what I see as a kind of ontology—or maybe more accurately a philosophy—of self-contradiction. He writes of the effaced etymological history of laysa, its forgotten “compound origin” in being composed of two words: la ‘aysa, as in “not being”. Extrapolating from this, El Wardany locates in laysa a figure for “the movement of an internal contradiction”; he proposes this in relation to his vision of writing as something that always exceeds itself. Through your encounters with Arabic literature so far, can you think, in a similar fashion, of a recurrent aspect of the language’s grammar or syntax that has been particularly resistant to translation, that presents a riddle each time you cross paths with it, or that could also be, for you, a metaphor for something in your own relationship to writing?

And then you wrote about moments in texts when you’ve “found something with a particular phrase or rewording”. Could you sketch an example of such a moment of felicity, and perhaps the alternative paths or phrases that presented themselves to you before you ended up selecting one? I would love to hear about anything that comes to your mind, but I’ve been dwelling a lot with your recent translation of A Horse at the Door by Wadih Saadeh, whose imagery and syntax often feel quite iterative, elaborating a topography of its own. When putting together that chronology of poems, were there points when you found the voice you needed in translation?

Speaking of Haytham’s essay, which is wonderful, and Wadih, I would melt down your two questions into the broader issue of translating critical phrases and fragments: ones that are difficult or otherwise have the load-bearing responsibility of working across a whole collection or body of work. The reason I lump them together, to follow the image of cracks and difficulty letting in light—or restated, allowing some sort of generative movement or dynamism within the text, that produces light/heat and allows the text to be read and create writing—is that both are a question of finding a knottiness and preserving it.

In the case of things I find difficulty in and that make me really have to write around it, it’s not so much words but particular constructions that have consequences in English. I find that lots of times my solution is to produce gerunds to reproduce the right balance between tenses. In Arabic this can look like, say, an initial past tense marker verb, followed by a whole passage or series of verbs in the present tense, to be understood as marked in the past. I find that complicated to deal with in prose especially: to somehow try and retain that sense of being in the past with the immediacy of verbs that feel vivid and alive and present, and gerunds seem like the natural solution. However, they drag with repetition, and though I like their sluggish insistence, it still feels like a failure: a sort of programmatic response. Sometimes a difficult thing is the fact that I have so many sort of shortcut ways to render things pre-programmed into me, that if I’m tired I sort of reproduce them unthinkingly; when that happens, it feels that something has gone wrong in my head with the idea of translation, that I am doing it wrong.

Wadih’s poetry is remarkably consistent in its simplicity and terminology, but coming up with a way to have these images sound and resound throughout the book requires that everything be translated with full awareness. After all, it is, at one and the same time, a distinctive voice and not a voice at all; its dryness or plainness or oddness become hard to reduce to “a voice” because you start to worry whether poems written over four or more decades can really share a voice, or whether it’s an illusion created by reading them simultaneously in a single present moment and writing them out. But I’ve gone with the variations being less chronological than typological: I’m really glad you feel that about the collection, because in the end I want it to be like that, the reader with the sense of a topography, something familiar constructed out of language.

I have translated a lot of Wadih before this book. The feeling that I found early on, and which I tried to keep hold of, was this sense of slight strain—almost frustration—like waves washing in and out but slightly more slowly than you’d like. I think it was only when I translated his very long poem “Dead Moments” that I felt it working properly. Before that I had translated “Seat of a Passenger”, but that is far less stable and forgiving; you can’t sit back and polish words or rephrase, it requires a sort of strong decision about the whole poem, that will allow its awkwardnesses and wildness. That left me unsure. Then came his short poems. For example, almost everything from “A Secret Sky” has almost no awkwardness in that sense: spare, spacious, small poems that allow themselves to be beautiful with a disarming facility.

Maybe I wanted to allow some of that beauty into the longer poems and some of the stringent awkwardness of the longer poems into his more beautiful imagery. It took a lot of takes and retakes before I had enough confidence to feel I was allowing the poems to be themselves. So, I suppose I was learning to read the poems. To express it with less mysticism, it sort of came together the more I read through it; I would notice with more and more clarity when something didn’t fit or flow, or if it flowed too easily.

Could I ask you to say a little more about the strong decision that you made when it came to translating “Seat of a Passenger”? What structural or stylistic considerations passed through your mind that eventually enabled you to preserve its wildness? Was it a poem for which you felt research was necessary (or, perhaps, more research than usual), given the abundance of proper names and contextual specificities in it?

I think the idea of researching those names and the biography that the poem hangs off was done by having read his poetry anyway, and maybe a sense of familiarity with what it is coming out of: my influences for that translation were the whole constellation of his fellow travellers, such as Sargon Boulus and others, and their poetry (there’s a poem by Sargon called “Meeting an Arab Poet in Exile”, which I translated at the end of an article by Youssef Rakha) and then The Crocodiles by Rakha (which has a rewriting of exactly this poem), and the poetry of Mohab Nasr, as well. And I had a couple of cracks at it; I translated it first after translating this equally long wild poem by Mohamed al-Maghout. Though the subject matter is very different, I think it influenced my approach a lot, in how to deal with the images and the way to balance its onrushing flow and multiple fractures and disjunctures.

To look forward a little to the future, within your own traversing of the landscape, which new directions do you see yourself moving in? Concretely, what projects and writers are next for you?

More collectively in the scene of Arabic literary translation, what is there to celebrate, and what to bemoan? I’m thinking of your translation of Ibrahim Farghali’s “Is it really necessary to translate Arabic literature?”, and his claim that “literary worth must be made the primary, indeed the sole, criterion for selection”, especially given a context in which Arabic literature in translation is often reduced to anthropological and political documents. How far do you agree?

I am currently working on a couple of poetry collections: another collection-selection of Ghassan Zaqtan’s poems, from the end of the last to the present day, and Samer Abu Hawwash’s extraordinary collection From the River to the Sea. Those are due to come out this year. I have been working for some time on constellations of texts by the extraordinary Golan Haji that are taking shape into books, and am looking forward to finally herding them between covers and getting them stapled. My translation of Mohammed Kheir’s next novel, Sleep Phase, will be coming out in May with the great Two Lines Press, who published Slipping. Then I have a translation taking shape of Hamdi Abu Golayyel’s memoir of his mother; I haven’t settled on a title exactly, though it was first titled The Field and then published posthumously as My Mother’s Rooster. It’s a question of finding somewhere for it, because it’s brilliant and strange and a joy to translate. At the very back of my list (only because I’ve tried and it’s very difficult) is trying to get The Men of Raya and Sakina published: Salah Eissa’s admittedly unwieldy, vast and detailed history of the circumstances around the Alexandrian murder-gang that operated in the 1920s. There’s really nothing like it.

As for that essay by Ibrahim Farghali: there’s a queasy question hidden in that argument—a plea?—about why there is a need to translate into English. Or rather, why the primacy of English; why, at least at one point, was it the sine qua non of success for some writers? I suppose the answer is money and what it can do: both the money you can earn and the way that money gives tangibility to success. You could get on planes, be written about skilfully, be called something mind-bendingly weird like “one of the most important voices we have from the Arab world”, and enter a literary world that seemed to stand, normatively, for all the world. At least, it saw itself like that.

The way it all works leaves me feeling very conflicted about what I do, frequently. The world we actually live in, in which the cultures which are the audience for my translations have great difficulty in recognising the humanity of those I translate (or, what’s worse, need be convinced of it by good prose), has made the always problematic ways in which these literary products are packaged feels genuinely obscene. I try to remember what is important to me. Anyway, there’s much wonderful translation going on and many more, especially smaller and more thoughtful, publishers taking books that they would have worried about before; there are always things to feel happy about, in that particular, very narrow, way.