Louis Poinsignon, with his soft, sloping shoulders, his thin frame wrapped in blue overalls, forever forcing his legs forward in high, black boots—Louis—a blue scarf always around his neck. Dead! No, I don’t believe it! In Vareau, his mother is howling, thumbs stuck in her ears, chewing tea leaves. Well, let her howl! We’ll see! I’ve still got a head on my shoulders; I’ll spit on this scrap of paper from Dispatch.

Deathly pale, Armand fumes for nine days, noticing nothing, not even that the frosts have begun. His mine shaft is full of mud, water is flowing thick as your arm on the ground; the pumps won’t work. Louis Poinsignon, with his smooth hair, blonde as straw, isn’t in the engine room, doesn’t come for backgammon. Off scuffling with the Prussians, like the others, while I keep watch over a pit. An ant, a clean, hardworking little ant, Louis Poinsignon, crushed underfoot—while I keep watch over the pit! His old mother’s howling, what’s that to me? The woman’s got no idea. He’s either dead or—Armand bites his tongue, at a loss—or that’s it . . . he’s not dead. He just can’t be dead. No, he isn’t dead. Louis is not dead.

On the tenth day he tells himself: After all, we’re not slaves. If Louis Poinsignon has fallen in the hills near Roye, it can’t have been for nothing. Pipes, trumpets, drums—just keep beating, thudding, rattling, booming. Cap into the corner, coat into the corner! Bath done! Now home! It’s seven in the evening. Armand’s eyes scan the signs in the town: Féréol Gide, Chemist; Widow Walter, Suits; Camille Ticeuze, Pawnbroker. It’s farewell, dear homeland, farewell!

Eleven o’clock, shaved and in the bedroom again, he says: “Goodbye my dear. I’m off to the inn to eat some mussels.”

“Quiet! Amélie is asleep.”

“Sleep tight, little Amélie.”

Miner’s cap over his ears, darkness in the winding streets: a November storm. Crouching in his stiff black leather coat, signal lantern hooked onto the third buttonhole, he passes the windows of the inn: Widow Walter, Suits; Féréol Gide, Pharmacy; Fat Camille, Butcher Shop.

Wet spray in the air, open fields: hey, you Prussians, you Bavarians, if you’ve got Louis hand him over. A circle of white light from Armand’s lantern dances ahead, two paces in front of the tips of his boots. Left, right, left, right! The clay sucks at his boots. Don’t stop, keep marching!

First through Dizennes: closed shutters on the windows; then past Uzaire’s estate and straight on through the barricades around the game park. Everything’s dead, the birds shot down. No guards! Ah, a rabbit! Now the main road to Craor and here’s a wagon.

“Take me with you to Roye?”

“Pay up and I’ll take you to Craor.”

“What about Roye?”

“No, I’m not going that far.”

He sleeps on sacks of flour till well into the morning, snoring, cowering, starting up with fright. Once he tumbles over backwards, grabs one of the sack handlers by the bare neck and rolls him around sideways over the planks; the fellow wanted to take something off him, steal it. A misunderstanding while half asleep, but now the glass of Armand’s signal lantern is broken in front, its thin casing twisted and his leather coat reeks of smoke; it stinks.

Cold, grey light; bare, endless fields! A roaring sound strikes the horizon hard; it becomes more distinct, cuts out, comes again: a long drawn out “thud”; double bass notes on the organ, reverberating deeply. Danger zone!

Soldiers cycle past on the right and left, moving towards the front, food tins rattling in their kitbags. Patrol units slouch along in twos and fives, guns on their backs and cold tobacco pipes between their teeth. They squint at the sky, their boots squelch against the clay. Left boot: “Is this still France?” Right boot: “Where’s France?” Left boot: “Where’s France?” Right boot: “Who knows?” Left boot: “Who cares?” Right boot: “Yeah!”

“Passes; show your passes!” No-one’s getting through. Off the wagon! A great throng of people from the village, all surging towards Bagolles, Little-Bagolles or Bordigaux, carrying sleeping bags, prams, handcarts and birdcages. Tomorrow Armand’s home will be a big city—there won’t be enough new wine or snails. All streaming away from the front, arguing: It’s not that urgent back there . . . Yes, it’s urgent! . . . The Prussians are firing.

Armand asks: “Where’s the road to Crataires?”

“Are you mad? There’s no getting through. The Prussians are firing.”

“Which road goes to Crataires?”

“What do you want to do there? Pick up your grandmother? Ready and waiting, is she?”

“Hey, you over there, look out!”

“Officer, Sir, my name is Armand Mercier. I must get through. I have relatives in Crataires, a woman, my sister who has two children, small children—one only eight months old. Her husband is in Toulon. I can’t let the woman be killed.”

“How long are you going to keep talking?”

“The woman is helpless. I’m from this district. My name is Mercier. They have to let me through. I can’t let anything happen to her.”

“I said—how long are you going to keep talking? See the sentry over to the left, get yourself a pass.”

“But look, Officer, it’s urgent, for Christ’s sake, please Sir, her husband’s in the naval command, he’s a Vice Sergeant Major. A man you can count on—as you would expect! I’ll never forget it if you help me. If you ever go through Dizennes, I live in the second cross street on the left.”

“Hey! Wait! You over there! Where do Your Lordships think you’re going? . . . You over there in the car: Where’s your pass? You don’t understand, well then out you get! . . . The sentry box, over on the left! I told you, on the left! . . . You too, that’s if you’ve finished talking!”

Soldiers are getting through. I’ll steal a uniform. Where are all the wounded? Where’s the battlefield? Standing in an alcove next to the guard, Armand examines the people. Size 1.8 would be right. A small wagon rolls past softly, slides around the barricade and also heads towards Dizennes. Two soldiers in it, stocky looking fellows, one wearing a red armband, his head bandaged. Thud! Thud! Violent rumbling! People everywhere, walking, driving, running faster.

“Good morning, comrade.”

“Down you get,” they roar. The one with the bandaged head presses his heel on Mercier’s clutching fingers. Too late! Armand is already kneeling on the sharp edge of the wagon floor and grabbing the side panel. The horse charges ahead; Armand’s black leather coat is swept through the filth on the road.

He pants: “To Roye; take me with you. I’ll pay.” Mercier is determined. Looking the two of them straight in the eye as he climbs to the top, he babbles: “My sister has two children. Her husband’s in Belfort, a Vice Sergeant Major, a reliable man.”

“We’re going to Dizennes. Opposite direction.”

“Sorry, I meant Dizennes. It was his heartfelt wish; I have to look after his children.”

The two in front are whispering. Armand squats down behind their backs under the round roof, squints over their shoulders and eyes their uniforms. Their whispering intensifies. As they approach Dizennes they slow down and the slim, healthy-looking one takes the reins, while the one with the bandage arches his back, braces himself suddenly against the upturned horse trough behind him and with a backward lunge—like a jumping jack—tries to wrap his legs around Armand’s. But Armand manages to grab hold of his feet above the ankles and he can’t break loose. He slides off the trough and bashes his head and left shoulder violently against two chests full of soldiers’ parcels. The thin man belts the horse. When they are sitting down again, Armand calmly wipes his hands on the cloth covering the chests, turns to the skinny fellow who’s driving and offers fifty francs in gold coins for his uniform and pass. Gales of laughter!

In a rage, the fellow with the head wound wants to drive so he can tip all three of them into the mud. Meanwhile, Armand, who’s been clicking his tongue and smiling seductively at girls strolling past, has spotted a little country lass wearing a ring of straw under the basket balanced on her head. He tricks the skinny one, who’s raring to go, into jumping down behind him onto the road and chasing her. She flees, swinging the basket in her left hand and panting, her mouth agape, as if in a silent scream. Instead of bedding the girl in a birch copse, however, the soldier finds himself on a sandy patch near the bushes where he has landed after being elbowed over a tree root—he sits there sorrowfully, rubbing first his chin and then his knees. Armand, who’s right behind, stumbles over him and, when he tries to get up, grabs him by the neck above the tie, and starts bargaining: “Now then, fifty—make it seventy—francs and the girl’s all yours! But be quick about it, she’ll be out of sight in ten minutes! We can still be brothers. I’ll let you go! There’s no other way.”

The soldier gulps and gasps like a fish that has been seized by the gills and is thrashing its tail back and forth. “You’re a spy! I’ll scream.”

“Scream then. You’ll be the one in trouble. Why scream? Just put my things on, go to the farm and take the lass. No questions asked!”

“No, you don’t! I’ll scream.”

“You’re asking for trouble!”

Still sitting in the sandy hollow, the soldier takes off his boots while he recovers his breath; with some colour back in his face, he asks nervously if the other man has an identity card. Quick as a flash, Armand rips off his coat and grabs the boots.

“You can have my foreman’s card for three days, for the journey, the police and the rest of it. Before they find out where you’re hiding, you’ll be back again!”

“What about my gear?”

“You’ll get it back.”

“All of it?”

“And ten francs afterwards.”

Dressed only in their shirts, the two of them double up in the freezing-cold, sandy hollow, eye each other warily and scratch their calves. While he’s pulling on Armand’s trousers, the skinny one finds something hard in the back pocket—a knife—and abruptly demands eighty-five francs. Armand pretends not to notice anything, accepts and places his foot on the soldier’s bayonet on the ground. It’s a deal.

Meanwhile, the injured man who’d like to dump the pair of them in the ditch is cracking his whip beside the cart. Armand wearing the light red cap; Pioupiou shuffling along in Armand’s leather coat, the signal lamp on his head, content with the eighty-five gold francs in his fist. Meet here again in three days. Pioupiou dances off into the distance, twirling his beard, gathering up the coat like a ladies’ gown.

Around the wagon, onto the road, northeast—Armand heads straight back into the danger zone. The day’s over. Straight on, against the flood of oncoming people, he falls in behind a munitions convoy! Horses slip on the smooth ice; whips and rifle butts fly at them. Booming sounds, behind on the right. And again, the echo rolls on, “drumm”, from somewhere behind him on the right, a long, drawn-out sound, “drumm”, that sets his teeth on edge.

On the other side of the stream cavalrymen without horses pass by in silence.

“I’m trying to get to my regiment. It’s Territorial-Reserve Battalion 81.”

“Does it still exist, this regiment of yours?”

“I told you: Territorial-Reserve 81. Ah c’mon! Where would they be?”

“Ok comrade, come along with us. We’ll sort it out. I know what’s going on.”

“Ah-ha, so that’s his regiment, 81 Territorial-Reserve!”

An NCO, a white-haired sergeant supervising access to the front, roars at him through a window in the gatehouse.

“You should’ve taken the eight twenty train from Craor—shirkers and traitors, the lot of you!”

“Here’s my pass.”

“You’ve got leave till the 26th.”

“I’ll do without it.”

An ambulance rattles up and whistles.

“Take this man with you.”

On the way, with the high-pitched wail of shells audible ahead of them, Armand quietly releases the door handle; he’s sitting on the stretcher in the wagon, full of anxiety about being taken to the 81st Battalion—and exposed. When the vehicle seems to be slowing and the road is dark and bristling with noise, Armand suddenly drops down backwards into the dirt. Startled, a cyclist jumps off his bicycle right in front of him.

A bright moon, a clear night, hills rising gently to the right and left, smoothly mown slopes. Avenues wind through the valley, past black-tarred timber shacks and sawmills; a windmill spins on the bulging hills. A white, flickering light beam, cast northward from the top of the mill, bores into the night and silently cuts across a glow that rises into the darkness from invisible places, lingers, disappears, then suddenly surfaces, fading in and out with the mist, till finally it slides off over the valley, kilometres away. People and wagons are forced apart. The convoy turns off to the left with Armand in tow, heading for Grand-Moulin, where the reservists and Louis Poinsignon are stationed.

Armand Mercier is weary. He’s riding one of the draft horses, eating corned beef out of a tin. Hill after hill! If only the wagon would stop creaking! Shells screech “whee-ee-ee-ah” overhead, and in between, a bleating whining sound: “meh-meh-meh”! Shards of ice crack under the horses’ hooves.

A long, broad road: nothing moving, just a munitions convoy. This is the way to Louis Poinsignon. Hot tears of grief well up; Armand digs the fingers of his left hand into the horse’s mane and presses his knees hard against the body of the panting animal. If he were on foot, he would just let himself sink down and not get up again for hours. The horse is taking him to Louis Poinsignon—but is Louis there? The village where the army is quartered will be at the end of the avenue, but Louis Poinsignon can’t be there. Weakness keeps Armand on the horse’s back as it trots, rising and sinking. Helpless, the animal just keeps walking up the silent road. Louis Poinsignon can’t be still alive—impossible in this place! This must be where he was taken.

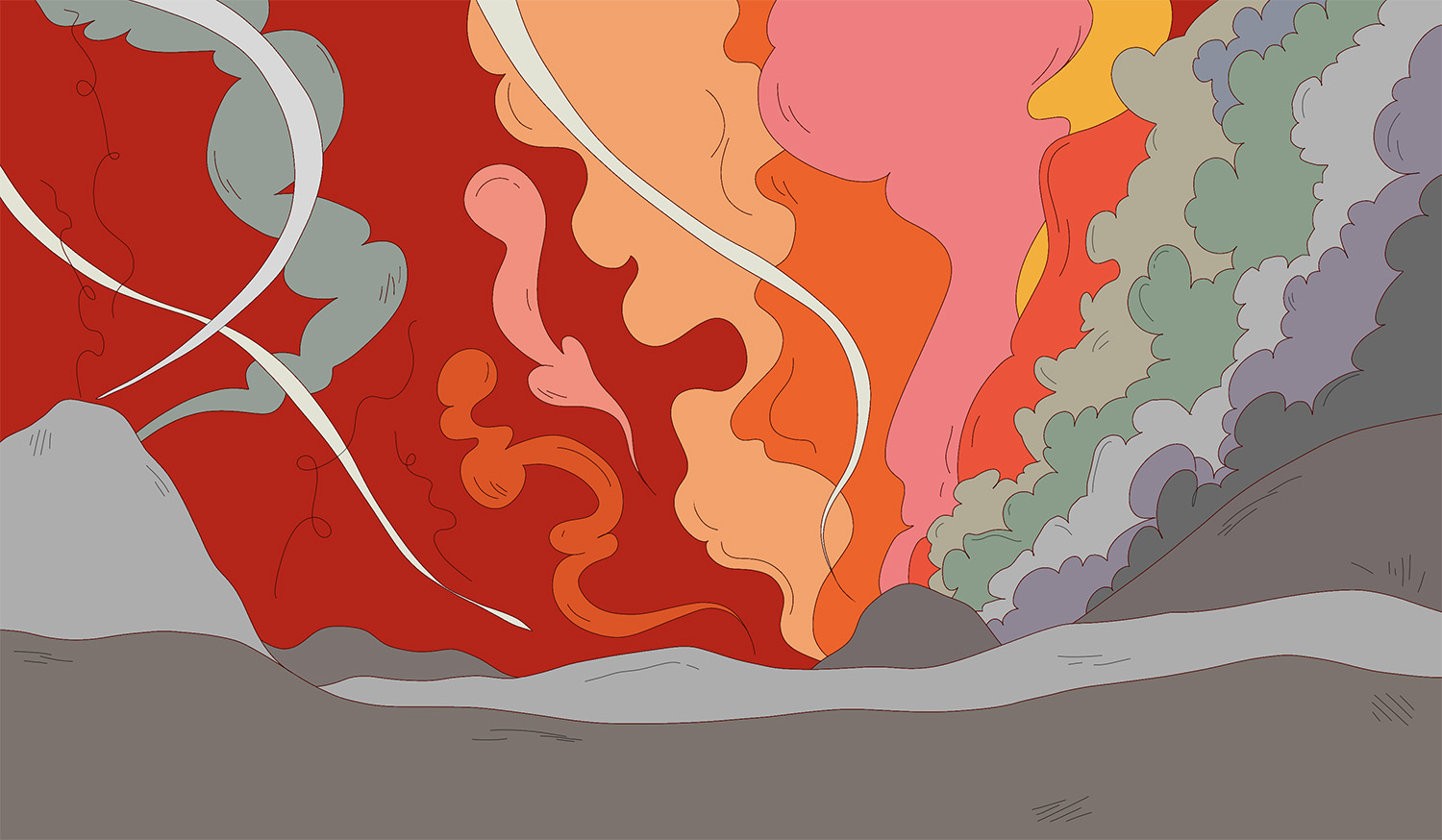

The sky is ablaze, its scarlet glow spreading from the right. Heavy-hearted, Armand gazes through his tears at the sky; the convoy moves straight on in silence. His eyes are fixed on the red glow looming up—now almost a half-circle on the horizon. Bewildered, bitter and disgusted, Armand gazes first at the fiery glow, then at the road and the forest as it slides past. His convoy turns onto the left side of the road and stops. Vehicles come rattling and crashing down from the village: towering transports, straw-lined wagons, open trucks full of the wounded, their bodies shot to pieces, with grenades snarling as they rear up overhead; moaning soldiers on whose heads stone walls have collapsed; others, half-suffocated, who were dragged gasping from the poisonous gas in the trenches. Bodies laid out in endless rows, one behind the other, wrapped in white bandages oozing blood—all that’s left of a delirious, nightmarish throng, twisting and turning in the teeth of the forces that had surged over them on the other side.

Louis Poinsignon—dead! Before the last car has whirred past the twisted convoy, waiting to move on, Armand has slipped into the forest. He wanders around the village, avoiding the area where the reserves are quartered. Debris comes pelting down from the half-grey, half-red dome of flames, is ground up and piled in layers. Bursts of fire, as high as houses, erupt from the earth: a hearth, a hammer, an anvil.

Deeply pained, Armand Mercier creeps out of the woods; around him on all sides people are fleeing, stealing off furtively. A shadowy figure comes running across the meadow with a fancy white hat in her hand. Without thinking, Armand walks along beside her as she steps between the first rows of trees. A dainty little lass, she has a tartan shawl over her left shoulder, but her skirt is spattered with clay right up to her hips. She says indignantly: “I live in Roye. We have to flee. My father and sisters are coming a little later.”

“Why, if it isn’t little Mademoiselle Nini”—he touches her tenderly.

She pulls away from him and looks around anxiously. “Oh God, so it’s you, Monsieur Mercier!”

“Mademoiselle Nini”.

“Now listen. No-one at home is letting on. I’ve only been away three days. I’ve been visiting my fiancé George, the bookbinder’s oldest son. He’s stationed here.”

“You mean you’re engaged to him?”

“It’s a secret. They’re not saying a word about it at home. God, isn’t this a coincidence? So it’s really you, Monsieur Mercier. I had no idea you’d been called up. What regiment are you actually in?”

Showing little surprise at all this, Armand places the hat on her head, pins it down firmly, takes the shawl, places it over her shoulders and gives her arm a squeeze: “Come with me.”

She smiled contentedly at him. “Armand, I had no idea you’d been called up.”

“Sure, I was.”

“If I’d known I would’ve visited you too.”

Head down between his shoulders, he wanders aimlessly around the forest with her: “Nini, there must be something to drink around here somewhere.” He gives her a pinch and whistles. She giggles: “How kind you can be. You know, Armand. Men really are so much nicer in wartime.”

As she snuggles up to Armand, her eyes close. They have stepped into a clearing. Someone comes galloping towards them on horseback from a side path, a military policeman. They scatter, but as she runs away Nini manages to wave to Armand to show where she is hiding. After a quarter of an hour there is a cracking sound in the bushes near Armand. Nini pulls him by the arm. “On your toes now, foot it!” she giggles, commanding him in a mock bossy tone, as they carefully push their way through the thicket, hands out in front: “‘Hey you, what’s your name? Where are you stationed, man? What are you doing hanging around here with a female?’ I’ve heard about this from George. The Second Lieutenant tells them: ‘No females allowed around here. Any soldier with a wench is done for.’ Armand, don’t you think I’m brave?”

She gazes expectantly at him.

“Yes, Nini, I do.”

Her eyes shine. “Oh well. Never mind about that! You know, I was with George in the dugout. There were other girls around too. When the guard noticed and came looking for me, George hid me; well, he tried to hide me, but all he had was a chest, a kind of bread safe near the front parapet—you know a tall, high thing—so I jumped into it on the spot and he lifted me right up. You know, I’d rather be shot by the Prussians than let a crude fellow like that catch me. A real lout! And in such a rage all the time he doesn’t know what he is doing. He’s been eying me off all along, the brute. Just imagine, Armand—I hope you won’t be cross if I call you Armand. You’ve been so nice to me today. Well, I was sitting inside the chest—set up between piles of stone—and the chest had a chink in front nearly as big as a head, made by shrapnel. So, there I am, when I hear the guard shrieking, carrying on and roaring as he looks for me all over the bunker. And George just kept shooting the whole time. He really knows how to shoot—one bullet after another—faster than all the others—though I didn’t see where he was shooting exactly. The Prussians couldn’t do a thing about it. And I wasn’t even frightened. I just listened as he went on shooting. He told me he wouldn’t have let a Prussian anywhere near me. He shot twenty or thirty of them dead and didn’t stop shooting for a whole hour. ‘Thud, Thud!’ again and again! I was so happy afterwards. Soon I’ll go back to him. How I love the war!”

Light flickers between the tree trunks in front of them. He works his way thoughtlessly towards the light with her; neither of them feels the cold. Suddenly ten paces ahead on the forest floor a harsh glare: signal lamps in the bog, men’s voices, spinning yarns. Two sentries in white fur coats, rifles by their sides, are laughing as they hop from foot to foot, swallow and chew something they fish out of a steaming metal pot near the lantern, sucking their fingers.

“He doesn’t notice anything. He wouldn’t know whether his cookpot’s there or not.”

“He’s an ass. I always knew that.”

“Who can get anything out of him?”

“Hah, who can? You tell me! Who can deal with an ass like that?”

“No-one!”

“That’s for sure, always the same. It’s the same too with that fat Second Lieutenant, who sneaks out whenever he can from the back of the field hospital. What’s more, he sends the stupid ass out looking for girls. And in the evening, guess what’s sitting on his lap!”

“We’d better watch out. He’s in charge of the guards at the field hospital today. But he won’t get anything out of me.”

“Not a morsel; I’ll polish it off myself first. He can snoop around as much as he likes.”

They squat around behind the lantern and pour soup into the cupped palms of each other’s hands.

All at once beyond the lights of the field hospital something flares up, dies down and flares up again. It’s straw. Men are tipping bedding from high up somewhere into a fire. Armand can’t move. While he was squatting there Nini had gradually stretched out across his knees; pressed against his chest now, she is breathing deeply and evenly.

The sentry swallows: “Yesterday, Pierre Chavanne, from my home-town, died over there. It was quite a business! So, there he was, lying in a room in the barracks with a fellow from Paris. He’s not feeling too well so the Parisian says: ‘Why don’t you give me your wedding ring? An orderly will only steal it later.’”

“Was Chavanne married then?” broke in the other sentry.

“Married? Nah! Don’t you carry one for luck too?”

The second sentry gulps loudly, suspiciously and then says under his breath: “I don’t have one. I’m not afraid of the Prussians.”

“Anyway, the fellow from Paris says to Chavanne: ‘Right then, you give me your wedding ring,’ and what do you know, he gets it. But Chavanne gets better and the Parisian has a rough time of it. So when the Parisian is well and truly laid up Chavanne begs him to give him his own wedding ring, and also asks the Parisian for the ring he gave him. He agrees. Chavanne is pleased and checks every day to see if his neighbour is dead yet—every morning and every night. But the Parisian gets better again and Chavanne gets into such a rage that yesterday at noon he has a heart attack. So, our Parisian ends up with both rings.”

“Is he dead then, this Chavanne?”

“He sure is.”

“What a dolt.”

“Nah, they’re both dolts. I’d . . . ”

“Sh! Watch out—guards!”

Rifles raised, lights out, single file through the trees.

Armand folds his arms sleepily. The little one is fast asleep with her head back, her hat flopping down loosely on her curly hair. She is breathing with her mouth open, her wet tongue visible through a gap between her teeth. When he presses her hat against her head the hatpin pricks her and all at once she is awake and alert.

Again, the rattle and chatter of gunfire not far off! Finally able to move his limbs, Armand steps over the pot, the girl on his arm and feels how wonderfully fresh the air is. He thinks: Even if Louis Poinsignon is dead, it must have been so nice to march, run, climb and shoot like him. A fine fellow—Armand is glad for him. He tells Nini about him and she too is full of praise for Louis. What if Louis is dead, thinks Armand, what’s there to be sad about! It seems to him that Poinsignon, the tall man in the blue scarf, has to be dead. Things are bound to fall apart—you can feel it in the air! We all want to rush headlong into death. Armand and Nini lark about listening to the “Thud! Thud!” Both hungry, they start running. Armand says: “Hop over to my unit and ask for the Second Lieutenant, but come back soon. I’ll be glad if he’s been shot. Then I can join the unit.” Nini runs off happily. And in the grey morning light Armand hears that the Second Lieutenant and many others have fallen. All that’s left of the unit are fresh reinforcements, strangers who didn’t know Pioupiou. Armand shrieks with delight, springs to his feet, smothers Nini with kisses and says: “Farewell.”

At noon he is digging behind the dugout—instead of skinny Pioupiou, who is off flirting on the farm. Two days of this: shovelling, bringing food and keeping watch.

But on the third day his hands go numb and it occurs to him that although everything is just fine and he ought to be overjoyed, it is after all not clear what has become of Louis Poinsignon. Towards midday, his heart is so heavy and his spirits so low, under such a pall of sadness, that he cannot rest. He picks up his knapsack, hangs the rifle over his shoulder and without saying a word takes himself off. And before he can turn around, he’s near the field hospital. They let him into the guardroom. Then a medical officer takes him along and starts leafing through an enormous book, as thick as an address book, chained to a special desk in the corridor. The clean-shaven man asks whether this Poinsignon was called Louis, or something else. And then Armand hears that on such and such a day his friend died of typhoid.

Armand Mercier doesn’t react. Stiffening, he says goodbye and goes off, telling himself: Well at least now I’ve found out what happened. It’s not until he’s in the woods, remembering Nini and the fresh, bright morning when he joined the unit that he begins to grieve, really bitterly, as if it’s only now that he feels his disappointment. His back aches, he feels torn, thinks: I’ll never be happy again. What have I got left? Only a uniform and a rifle! No coffin, not even a corpse—he’s left me nothing. He has very unkind, ungracious thoughts about Louis, who simply went off and died of typhoid in a field hospital, and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

And in his anger, he keeps walking more or less towards his post; completely forgets he’s wearing a uniform after a while, and howls. He thinks about home, about his wife and Amélie, which causes him such grief that he can’t stop crying—realising that this is where he too will die, of typhoid or something else. “Oh Louis, Louis,” he sighs and sits down on the ground near the baggage wagon. Absorbed in his grief, he wrings his hands and waves his arms up and down. A wagon driver plonks down in front of him. Armand doesn’t hear his curses. The Second Lieutenant pulls him to his feet. Glassy-eyed, Armand stares him in the face, inadvertently punches him on the bridge of the nose, then sits down again by the wheel and—feeling keenly his own misery and the misery of the world—laments his fate.

After five minutes, he is seized by four MPs, shaken and cudgelled. Out in the open, knapsack strapped on, he’s tied with ropes to a pine tree, arms above his head. Two hours he has to stand there—in the freezing cold.

The second hour is up. Armand walks away from the tree, stiff and angry. They have taken away his rifle and sabre. All he wants to do now is run across the field, get his rifle back, charge at the Prussians and fire—and keep firing. Instead, he is sent running past the trenches to the work gang. The trees in the front part of the forest are being lopped, their stumps left in place, their tops touching; arranged in stacks and rows, almost like cavalry rooted to the spot, brandishing lances at the enemy. His work gang is using pickaxes and massive poles to knock down two small foresters’ huts. They chop the frozen earth, scrape off the dust and fill the bins and sandbags, convoy leaders cursing, misfired mortar exploding against a tree trunk, frenzied work. All agitated, their eyes looking around wildly to see what’s behind? Artillery fire heavier, ever closer.

Back through the forest, smashed now all the way to the railway cutting. Armand curses as he tramps along with five others, till he reaches the inn near the sluice behind the embankment.

A white-whiskered villager in steel spectacles is tottering along behind him on wobbly knees—a fiddle under his right arm and in his left a hedgehog, wrapped in a blue handkerchief. Does anyone want to buy the fiddle? In the mood for a bit of black humour, Armand offers the old man two brandies to play a country waltz. A sapper says to his neighbour: “When the old fellow leaves, let’s take the fiddle off him.” Outside, right next to the door, straight into a pile of branches fly old man fiddle and hedgehog, still in the blue handkerchief! Shrieks from the old fellow; the fiddle is under the sapper’s arm; the other four soldiers are onto him. In a rage, the sapper bashes the fiddle against the tip of his boot. Uproar on all sides! The robber threatens the greybeard with the shattered fiddle. Armand snatches up the hedgehog in the handkerchief with an “Ei, ei”.

He is about to stick it under his jacket when someone grabs him by the elbow, flings him around to the right and shrieks: “There he is! The rogue! We’ve got him now. There’s my uniform.” It is skinny lover-boy Pioupiou, in the miner’s coat, the lantern hanging from his buttonhole—a military policeman right beside him. Hullabaloo! Armand’s dragged out. Pioupiou—handcuffed—roars: “Spy!” They’re hauled before the captain in the dugout.

The MP presents arms, black sabre erect, and says he saw Pioupiou here prowling around in taverns with a pile of gold coins, probably stolen. The fellow claims to be a soldier and to have been robbed by this miner, Armand Mercier. Pioupiou snivels: “There I was, just driving my wagon along, when this Armand turns up, with three others and grabs my horse by the reins near Dizennes.” He swears they lured him to a deserted farm and stripped off his uniform: “Those three others had spiked helmets, great big ones, so they must’ve been Germans and spies, what’s more, like Armand.” And what about the gold? He borrowed it in an inn of course.

Armand Mercier fumes, muttering under his breath; looks the other three mournfully in the eye. He bends forward over his belly so he won’t squash the little hedgehog. Better to stay here and fight than go back to the tree. He’s already lost Louis; that’s it, enough is enough! Damn that rogue Pioupiou for getting in his way! Ignoring a venomous look from Pioupiou he flatly denies being Armand Mercier: waves his identity tag. “See!” Armand pleads. They shout each other down, don’t notice the captain smiling scornfully, tilting his head and waving the policeman off. Armand’s not finished; thrusting his fist in front of the fellow’s nose, he splutters: “You, so you’re the honest one, eh!” Face swollen with rage, he turns to the captain: “He was paid. Eighty-five francs he got. I came here to bury my friend Louis Poinsignon, who died of typhoid in the field hospital. But this fellow here is scum; he deserves ten hours tied to the tree. Captain, Sir, he’s just scum—a rotten troublemaker. He’s no comrade of yours, Sir, this rogue”. At the Captain’s glance Armand shrinks back. They both get two hours on the tree for the next three days. Orders to the Sergeant: let them busy themselves helping sappers dig trenches on the forward defence lines. The Captain roars with laughter as they’re led off. Armand thinks: him, with the harsh, angry voice—he’ll be dead too, soon enough.

At nightfall Armand’s convoy sets out from a village riddled with shrapnel, just behind the railway crossing. Full of rage, dragging his pickaxe, Pioupiou marches behind Armand; he’d like to strike him dead over the two hours at the tree. Mercier dodges as he feels kicks from behind, but doesn’t turn on Pioupiou. No use cursing here! We have to fight. Either we fall or the Prussians fall. “What a funny creature the hedgehog is! There, there, poor little thing!” He touches the hedgehog nestling in the pocket handkerchief under his battle jacket.

Two cows, scorched black, come hurtling out of the village below the railway embankment; a burning dog, dancing and howling, seeks shelter in the gaping stomach of a horse that is hissing and giving off smoke. And now, the dugouts: men stream through the narrow connecting trenches; pushed along, one behind the other, from left and right, they flow together—past the latrines in pitch darkness, past the checkpoint with the telephones and the stinking place filled with moans, where the dead and wounded are piled high.

Finally, the very front row; in the dim light of the pocket lamps silent shapes become visible under the ramparts, their faces grey and emaciated, eyes hollow, their coats stiff with clay, pointing their gun muzzles out into the darkness. They climb silently through the breakout points, slip between the rows of barbed wire, cross shell-holes on level ground, forced forward, rifles on their left shoulders, spades under their right armpits, blades to the fore. Sentries on the ground at the front oversee an endless line, like a conveyor belt. The shovels work in secret, no clattering, just rummaging, whispering and moaning in the darkness. “Oh, is something coming?” They whisper, touch whoever is next to them. Night passes, now it’s back to the listening post! Relief! The reserve unit marches from behind into the icy pits, dragging in railway sleepers for cover, tin for the wind gaps, handsaws, whipsaws, chisels, axes, ropes, clamps. Telephone wire is unrolled.

The first rounds of fire from the batteries of field howitzers on the other side come crashing down. It’s here now, the moment of attack. Hollow-eyed men have climbed out of the trenches, discarding their stiff coats. They’ve climbed up into the grey dawn, surging up everywhere, wave after wave. In the open their faces are fixed in the grimace of the dying—men beyond thought or feeling. They are like cats that jump into the swamp and drown—it’s thirst, sheer thirst. They run towards the empty field in a wild, bloodthirsty rage. But it is not quiet, this field; it is just silent, breathing, waiting. The small guns are coming closer, decoys—like bacon used to catch mice. There are so many, many more on the other side.

Listen: radumm, dum-dum! Dull booming and the deadly rattle of artillery!

This is it, merciful God. This is it.

How those Prussians can shoot! The terror raining down; the screaming rage! Keep going! Keep at it! If only we were already there! Don’t shoot! Just bayonets! Knapsacks down! Caps off! Boots to the fore! Rifle butts up!

Again, the cannons: radumm, radumm! Whining bullets!

Armand grinds his teeth; he’s thrown away his rifle. Now he lifts the shovel blade over his head defensively, pulls his bayonet out with his left hand and brandishes it. The hedgehog pricks his upper thigh. Now we must run. Like everyone else he swings his arms, roaring: “Onward, onward!” Oh, oh, radumm, radumm! He’s a mere echo. Mouth open, he yelps at every shot; forces his eyes wide open: where are the big guns; we’ll get them—those Prussians! It’s their doing. They’ve occupied our country. They’ve killed my friend.

Louis! Louis Poinsignon! Louis!

Revenge! Revenge! Mouths and legs and lurking bayonet points: a thousand hungry bayonets. White spikes sliding up and down! A forest of iron that rocks and sways!

How it all shudders and shakes!

That’s what it’s like! Left, right, soldiers stumble forward as they run. Not a sound to be heard. Wooden dolls, they tip over—like rams knocked off their feet.

Infamy, betrayal, infamy!

The Prussians’ fire stings like water, ice-cold water. Now there’s something behind him! A shove in the back! A stab between the shoulder blades, something cold and long—a fishbone that you can’t swallow, forcing its way forwards and up into your throat. It’s a bayonet, Pioupiou’s—he staggers past. Stop! Braced against a knapsack, Armand squirms; heavy footfalls; the next man steps over his knees. The machine guns roll on. “Come on then! Come through! So, you want to keep coming, do you? Revenge! I’m in this, me too!” The hedgehog pricks. A half numb hand unbuttons the little creature. It tumbles out of the handkerchief and rolls away. On the ground now, Armand yelps: “Forward! Roar on, radumm-dum!”

A volcano of shrapnel erupts. Still more shrapnel! They run back amid the clatter of bullets. German bugles blare out. Hoorah, hoorah, hoorah! A black cloud, then something stony, something iron; an armoured car rolls across the gravel! Nearer and nearer!

“Hoorah, hoorah!” they roar. Radum!

Machine guns back! Reserves back! No rifles! No caps! Yes, they’re back again; they’re leaping into the ditches. The Prussians!

Armand has earth between his teeth and a white mouth.

Crushed, ten steps in front of him, is the pastry cook, an old bachelor who told the best jokes before going to sleep; lying on his pickaxe, a little student with round cheeks who looks eighteen, though he was twenty-five; the captain—eighty-two steps further on. Who knows all their stories? All the way to the embankment the forest is lost.