To be honest, even though I expected all this, it seems I didn’t really want to acknowledge what was going on. Expenses aside, I have put so much time and effort into this. I hid my sorrows from her, and many times joined her in smiling while I felt a fierce itch clawing at my throat. It sounds silly, right? To mourn the loss of someone and want to make sure they die because you don’t want to waste that mourning. Since yesterday, I kind of felt that nothing was going to happen. She held her brush in her hand and kept staring at herself in the mirror. I say “herself,” but I can’t be certain if she knew that it was herself she was looking at in the mirror. She looked as if she was watching someone else through the window and was waiting to see how they would brush their hair. Is it really possible to forget one’s own self? Or to forget that mirrors reflect? I went and stood behind her, took her hand holding the brush, and gently moved it over her hair. She pushed my hand back to show me she knew how to do it on her own. I sat on the bed and looked at her. The veins of her hand and her soft straight hair. When she finished brushing, she turned to me and looked at me as if she was just noticing my presence. “Who are you?” she asked. I felt a chill creeping over my body. A coldness appeared out of nowhere and circled around my legs. I got up to close the window, but it was already closed. The sky was so cloudy you could not tell where the sun was. It was the first time she had asked the question. She had forgotten what she needed to do before, but she had never forgotten me.

I turned and looked at her. She was still waiting for an answer. She had not forgotten her question. Everything was still hers, her hair, her hands, her brows, her cheeks, her lips, and the lines around her eyes. Her eyes, though, were not hers. They were the eyes of a stranger who had been thrown there from another universe to replace mom. Aren’t people their very eyes? “It’s me, my dear one, your daughter, Mitra.” She kept staring at me silently with anxious eyes. I introduced myself again. My voice trembled, but perhaps she didn’t even remember what it meant for a person’s voice to tremble. I walked slowly toward her, held her hand in mine, and, imitating her short footsteps, took her to bed. I helped her wear her nightgown, held her in my arms, and tucked her into bed. She had lost so much weight that it was easy to do such things for her now. Then I gave her her pills and caressed her until she fell asleep.

When I woke up—it was already late, almost noon—I called Dr. Missaghian. When he heard my hello, he asked, “Mitra, is that you?” It sounded busy around him; maybe he was at the hospital. I don’t know whether he had already gotten and saved my number through mom or my aunt, or he had just recognized my country code. The last time I talked to him, it was five years ago, a month or two before I left Iran. Had I told you he had confessed he had feelings for me back then? I don’t think I did. I told him I loved someone in Italy and that was why I was moving there. I lied. I can't explain why. Back then, I lied easily, needed pretty good reasons to tell the truth. It wasn’t like these days when every lie spirals me down into anxiety. Maybe I was afraid I would fall for him and reconsider leaving. I told him the latest about mom. He said there was really nothing we could do, but suggested I increase her Memantine dose. He said the change in her living conditions was speeding up her memory loss. He said I should be more attentive and keep dangerous objects away from her to avoid her doing something violent or harming herself. Mom and violence? He said I should lock the entrance door. He wanted to know more about me. He sounded excited, and I was not in the mood. I made an excuse about mom needing help. Then thanked him and hung up.

The house was a mess. I started to clean up, did laundry, and washed the dishes. We do have a dishwasher here, but washing the dishes helps free my mind. I made coffee for mom and tea for myself. I took the milk, cheese, butter, and jam out of the fridge. I don’t like these Swiss cheeses with their awful smells, but mom loves them. I cut some slices and prepared a tray with some, along with toast, coffee, and fresh basil, and took it to her. She smiled, seemed once again like her familiar self, but then said she loved it here and asked whether she could stay here forever. Forever . . . I wondered if she could remember why we had come here. I wondered if she could remember that in a few hours the doctors would come to help her do what she so adamantly had decided to do. “Of course, we can, mom.” I was not lying. Doesn’t “forever” mean until people are alive? I didn’t say more or ask her anything, to be able to continue believing that she still remembered her decision. Am I coldhearted? Am I selfish? Maybe, I don’t know. What would you do in my place? When she first made her decision, she was so determined I didn’t doubt it even for a second. She wasn’t even willing to do another treatment session. At the time, she was still lucid. Maybe not completely, but she only forgot little details. So, I promised her. I told her I would help her out even though it was very hard for me, because that was what she wanted and that was all that mattered. I wanted to be like her who, despite being heartbroken, encouraged me to leave Iran so that I could study in my favorite discipline in my favorite university. And all these years, she smiled in front of the Skype camera, telling me everything was fine and our home would be there for me to come back to whenever I wanted to, to make sure I would not falter on my path to my dreams.

A bit later, auntie called. I put my phone on speaker for her to talk to mom. I kept praying she would mention mom’s decision so mom would then confirm it or at least show surprise so I could know what was going on in her mind. It was a false hope. What could anyone say to someone who had made up their mind to end their life? Auntie only asked how mom was doing and recounted a memory from their childhood that mom too seemed to remember. She then asked me when the doctor was coming. I said in the afternoon, but even then, mom didn’t show a reaction. Auntie said goodbye and, with a muffled voice that seemed to be falling down into a well, told mom that she loved her, asking her to take good care of herself. I'm not sure if she said it out of habit or she really believed there was another world in which one had to take care of oneself. Whatever she meant, taking care of oneself in this world doesn’t mean much. Look at mom. All the exercising and healthy eating for her to end up here in her sixties.

Someone rang the bell. Mom stared at me. I had no idea what she was thinking. I couldn’t tell much from her eyes anymore. I went to the door. I could hear my own heartbeat. I thought maybe I had misremembered the time. It was the nurse. She had come to do mom’s painkiller injection and check her blood pressure. I couldn’t guess if these people really care about a person not feeling any pain until their last moments or they just do what they need to do automatically, like a machine. When the nurse left, I went to hang the laundry. I was unsure why I washed mom’s clothes and what I was going to do with them. It was easiest to not think about all of this and continue with the daily routines until the very end. Like the nurse, continue doing what I need to do without thinking too much about the future.

When evening came, mom started to get restless. The mountains are close by here, so the sun disappears behind them and sets early. I don’t know whether I should call it a sunset or not. Don’t sunsets happen on the horizon? It was around five when the sky got dark. I turned the lights on, so mom wouldn’t feel sad. I mean just the few table lamps and the bedside one, since these houses don’t have much other lighting. Then I brushed her hair and put her nice green silk dress on her. She didn’t even ask why that one. She was quiet again. I put her necklace on as well as some make up and talked to her about her beauty. She smiled but didn’t say anything. Was she becoming a stranger again? I tried not to think of the reason behind her silence. I was unsure of what to do next. I put on some water to boil. For me? For mom? Or for those who would soon arrive? Perhaps the procedure puts some pressure on them too. You cannot get used to such things, can you? I was lost in these thoughts when the doorbell rang. I froze in my place. I had been waiting for this moment for days so that our excruciating wait could come to an end, but my feet didn’t dare move to take me to the door. I added some water to the glass teapot and stood there watching the tea spread its color throughout the water. The doorbell rang again. I started moving. As I walked along the hallway, I threw a glance at mom’s room. And once again, I saw her, I saw her eyes, the eyes of a stranger.

By the entrance door of the house, there is a full-size mirror you unwantedly look at every time you are about to open the door. I looked myself up and down but tried to avoid looking into my own eyes. Was I wearing the right clothes? Maybe I shouldn’t have worn black, but these were the only flattering clothes I had with me. Why didn’t I think of this day when I packed? What kind of clothes are the right choice for such an occasion? Bright colors or dark ones? Do you know? I opened the door. Two broad-shouldered men, not in white coats, but in dark blue suits, the same color as the sky of the hour, stood there waiting. They said hello and introduced themselves. I don’t remember their names. I wasn’t really paying close enough attention to remember. One of them was so tall he had to duck a bit to step through the doorway. I responded to their hellos dryly. I doubt that I even smiled when they did. I just managed to sift their English words through their heavy German accent and say some words of my own.

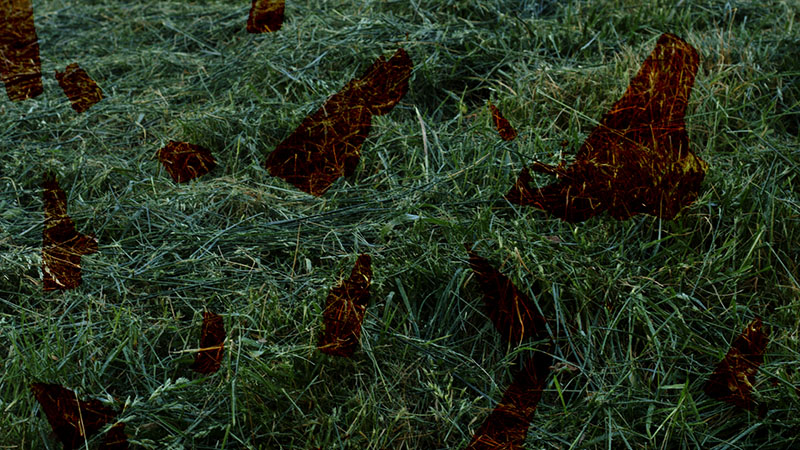

When they entered the room, mom seemed the same. “Who are you two? What do you want here?” she asked the moment she saw them. The men seemed surprised. They didn’t need to understand what she was saying, because the lines on her face screamed of anxiety in every language. The men said something to one another. As if she had suddenly come to herself, mom said something in French. Perhaps she just repeated her questions. This time firmly, with confidence, exactly like when she used to teach. Memory is such a strange thing, isn’t it? In the face of danger, it somehow gets itself there to save one’s life. Why didn’t I learn French from mom? Even my cousins learned the language from her, but, stupid me, I stubbornly resisted it, just because I didn’t want to follow in mom’s footsteps. Now I’ve reached a point in life where I only want to set foot on already-trodden paths. I have no energy left to discover new paths or my possible hidden talents. Though this is a German-speaking region, most people here speak French too. The taller man was busy talking with mom, while the shorter one, I can’t remember with what words, politely asked me to leave the room. He told me they wouldn’t be doing anything now, would just want to talk with mom alone. I was worried about her. What am I saying? Worried? Worried that she would die or that she wouldn’t? Which mom was I worried about? The one who was now defending her life with words I could not understand was the very stranger mom did not want to keep alive. She was the one mom wanted to kill because she didn’t want our image of her change. For mom’s sake, I had to distinguish between the woman lying on the bed now and mom. Who had the right to make decisions about this body? The soul that had accompanied it for sixty years or the one who was appearing more and more in the past few days? How can we remain determined about our decisions for the future, when we are constantly changing and whatever decision we make ends up being not for the one making the decision but for the new one following it who has new tastes, new thoughts, new pleasures? How restrained would one's new self be to implement decisions made by one's already old self? How far should I go to keep the promise I made to mom three months ago? Someone tapped me on the shoulder. It was the taller Swiss guy. I didn’t feel like looking all the way up at his face, looked instead at his red tie that had images of tiny black horses scattered all over, as if they were left to themselves in a meadow. The man repeated their request for me to leave the room. I went to mom’s bed and kissed her. Mom, or the woman. The forehead was the same. Then I walked out.

I went to the kitchen and arranged the cups on the tray. I thought about all the useless efforts I had made, while resenting myself for being angry at mom for staying alive. Maybe my efforts had not been useless after all. Didn’t she say she liked it here and was enjoying herself? I tried to busy myself with something. I found the recipe for a quince stew on the internet. I started peeling the quinces, throwing away the parts that had gone bad. I don’t know if there is a quince orchard here. The day we arrived, our landlord had left us a basket of quinces on the table. They were unripe and hard then. I waited for them to ripen, and now parts of them were already rotten. I then washed two cups of rice and let them soak in water. As if I already knew what I was going to hear soon. I was sautéing the quinces when I heard mom’s bedroom door. I poured some tea and left the kitchen with the tray. Before the men could say anything, I told them I had prepared some Persian tea for them. I was not even certain whether adding the adjective “Persian” to the tea would entice them. They thanked me but refused to have any. Then they went ahead with their explanations, saying things about rules and ethics and moral codes. That because of mom’s reduced cognitive abilities, they could not go ahead with the injection. They also said they could not return our money, except for the ten to fifteen percent which had been for funeral fees. They explained that all this had been detailed in the contract. I guess in its long list of clauses or whatever. They didn’t even apologize. No one apologizes for not killing someone.

If you were here, you would insist on your rights. You probably would say something, confront them, ask them questions, or at least get your money back. But I just stood there, holding on to the tray, and watched the movement of their lips. Maybe a sigh left my lips, I can't tell. I returned the tray to the kitchen and walked the guys to the door. When I closed the door behind them, after the tall one bent his head a bit and stepped out, I went to mom’s room. She was still in bed, anxiously murmuring things to herself. I stepped closer and embraced her. I couldn’t understand what she was saying. Her unclear words seemed to be French. She didn’t embrace me back but grew calm. I gave her her pills. They might not cure her, but they do diminish the suffering of being awake, and so a little bit later, she fell asleep.

It was around nine in the evening when auntie called again. I didn’t pick up. I kept staring at the TV and the news anchor, whom I couldn’t understand, when mom came into the living room with her walker. I felt happy seeing her, as if she had just arrived from a trip to faraway lands. I smiled and told her to join me for dinner. I helped her to sit and served her some of the quince stew with rice. She began eating slowly. I asked her if it was good. She said yes, then asked me, “my dear are they coming tomorrow?”

What could I tell her? When I recovered my senses, I realized I was just sitting there silently, staring into her eyes. “Yes, mom,” I finally muttered. She seemed to feel a hesitation or a question in my eyes or my voice that made her reach out, hold my hand, and tell me that she did not have any doubts. She said she was thankful to me and that I was doing her a big favor. I held her closely in my arms and stared at the empty wall and the suitcases behind her. How could I tell her we had to gather our stuff and check out tomorrow? Where were we even going? Her visa was expiring. What plane tickets could I get for her? I couldn’t send her back to Iran all by herself. Especially to her now empty house.

When I took her to her room, the moonlight was spreading over her bed. She said she wanted to stay awake and finish reading Céline’s Journey to the End of Night. She had bought it in the original French from the bookstore at the Geneva airport to read while we were here for the month, and she was almost done. She asked me to bring her coffee so that she could stay awake longer and finish it. How lovely it was to be only worrying about finishing one’s book before the end of one’s life. She suddenly seemed so much like her old self that I wondered for a moment whether she had been cured. I went to the kitchen and brewed some coffee. I had a headache. I took my medication bag out of the suitcase and looked for a painkiller. I took one and tried to swallow it. They always get stuck in my throat. I noticed the pack of Clonazepam I had asked a friend to bring me from Iran, anticipating the depression and insomnia following all this. It was full. Twenty pills. I put the pack of painkillers back in my bag, but not the Clonazepam. I knew now that mom was adamant in her decision. I knew I had to hold on to my promise. I was not going to let the stranger take over her again. I wore the dishwashing gloves and took the pills out of the blister pack one by one.

As mom sipped her coffee, I sat right by her. Perhaps it didn’t taste good, was more bitter than usual, but she didn’t say anything. Putting up with it or having forgotten the scent and taste of coffee, I'm not sure. Do people forget tastes too? I wanted to caress her but stopped myself. I was worried about not feeling any guilt, of turning into one of those coldhearted killers in the movies. When she began to get sleepy, she put a bookmark in her book, and said goodnight. “Love you, mom,” I replied. Her lips moved a bit, as if she was trying to smile or say something back, but she fell asleep before she could. I kissed her. I kissed her eyes. Mom’s eyes. I put her book away. Only a few pages to the end. When I left the room, the moon was still shining on her.

To distract myself, I began gathering our clothes and arranging them in the suitcase. As if everything had gone ahead according to plan. I could not tell whether our clothes were simply cold or still wet. Then I went and lay down on my bed, trying to sleep. I decided against brushing my teeth to avoid facing myself in the bathroom mirror. But I couldn’t sleep. The room was dark, but there was light behind my eyelids. I decided to come here and write to you. To talk to you. You know I don’t lie to you. You know I didn’t do this out of selfishness. I would be more than happy to take care of mom for years if that was what she wanted, but she didn’t want that. It’s better too for the stranger, right? I don’t even know what twenty Clonazepam pills can do to a person. What if they just make her feel bad? What if? Do you see? I’m talking like a killer who is worried their victim is still breathing. But killing someone is not always a bad thing, is it? What’s the difference between what I did and what the Swiss were going to do? Is mine bad because it doesn’t follow the protocols or as they said the ethics? Even what the Swiss do does not follow the protocols in other countries. The rules of no other country allow euthanasia for tourists. Do the Swiss begin to feel guilty for what they do when they go to another country? Please don’t think it stupid of me to write to you in an email. Your tomb is so far away, but even then, coming to your tomb to say these things to you there would be stupid. I wish you could answer as quickly as you used to. I need at least one person to tell me I did the right thing. Why are we in so much need of hearing this one sentence? My phone keeps blinking every few seconds. It’s Dr. Missaghian. He is sending text message after text message. Perhaps he wants to give his condolences and ask if there is anything he can do. If I tell him, he will surely say I did the right thing. Should I tell him? I wish you were here to tell me what to do and then I would feel assured because whatever dad says is always right, even if it means he is admonishing me and bringing me to tears. Why am I not crying now, dad? Have I become hardhearted? Maybe I haven’t yet accepted reality. I should go to mom’s room and see her. I should touch the coldness of her skin. And, like seasoned criminals, run the empty pack of pills on her fingers. But I cannot. My legs are not collaborating.

Towards the end of Journey to the End of the Night, in the very pages mom did not get to, when Robinson’s body is being taken to the police station, Ferdinand, who doesn’t want to believe his friend’s death, keeps walking to the left and right instead of following directly behind the stretcher. In the middle of the way, he separates from the others and walks through some fences toward the Seine to watch the boats. I too wish not to go to mom’s room, dad. Not to face what I just did. To walk left and right. To get drunk. To dance. And not to believe. To go to a red meadow full of horses. Get onto one of them, put my cheeks on its mane, and let it run beside the rest of the pack, without kicking it on the side to make it go slower or faster, or guiding its head in any direction. I want to let it take me wherever it wants and choose my destination. I’m tired of making decisions, dad. I want to sleep. One doesn't need to make decisions while asleep. In that realm, there are neither responsibilities nor ensuing regrets. I wish I had kept one pill for myself. There is light shining into the room. The birds have started chirping like every other day and the sun is rising. It is rising behind the high mountains. I don’t know whether to call it the sunrise or not.