Theo Verwey rocks back and balances on the rear legs of his chair this morning. Don't, I want to say, you will fall over backwards. I have never seen him sit like that. He is deep in thought. The palms of his hands are pressed together tightly and his index fingers rest against his mouth. Keeping guard of his mouth this morning? Does something want to slip out? He is not that kind of man. I do not read him like that. Although I admit that I do not read him well.

I am sitting with the bulky stack of cards in my hand, the dictionaries open before me. The first card in the stack is da. The last card is dyvelaar.

"Da," I say, "where does that come from?"

Da or dè is probably an abbreviation of daar (there) and was noted for the first time in Afrikaans by Pannevis as deh and in the Patriotwoordeboek as dé, he explains.

"Dyvelaar," I rhyme teasingly, "as in twyfelaar?"

"Dy-vel-aar," he spells out, "or dy-huid-aar." A vein in the lower leg, the vena saphena, he explains.

"Not to be confused with the femoral artery, the arteria femoralis."

"What would the dermbeen be? And the dermbeendoring?" I ask.

"The dermbeen is the topmost, flat part of the hipbone, the ilium, and the dermbeendoring is any of its peaked protrusions."

"Dermbeendoring," I say. I repeat it a couple of times to feel the uncommon sequence of sounds in my mouth.

We are still listening to Monteverdi madrigals. Madrigali guerrieri e amorosi, performed by the Taverner Consort and Players on historical instruments, conducted by Andrew Parrott. This is not my favourite music by Monteverdi, but I do not object. The next track is exquisite, though, and we listen to it in silence. "Su pastorelli vezzosi. Su, su, su, fonticelli loquaci." (Arise, comely shepherds. Arise, babbling springs.)

Theo leans back in his chair, his hands behind his head, and it must be the effect of the music, for I am unexpectedly overcome—overpowered—by a sexual receptivity to him in a way that I have not experienced before. The sensation is so intense that I feel slightly nauseous and have to bend forward. God forbid, I think, I could slide my hands under his shirt, over the chest, and let them nestle in his armpits.

It takes a while to regain my concentration. I continue to page through the dictionary. I read the definitions of "death" and "life." This morning I rose with a heightened sense of mortality. The soft armpits, the powerful male stomach, the tender groin and instep of the foot. What would it be like, carnal love with this man? A day or two ago I told Theo Verwey about the passionate meeting between the man and his wife at the end of the book. I mentioned that they have sexual relations standing up. I told Theo that she clasped her legs around her husband's body, but did not mention how ardently she kissed him. In the small hours I dreamt of a seducer—someone focusing obsessively on me. Something threatening in the man's attentions. In the soft, compressed space of the dream he forced himself on me with an offensive licentiousness. I woke up and too soon lost the mood and content of the dream.

This morning I am inclined to think that it was death who had fawned upon me and flattered me like that last night. Why not? Would I not be able to clothe death in this way in my subconscious?

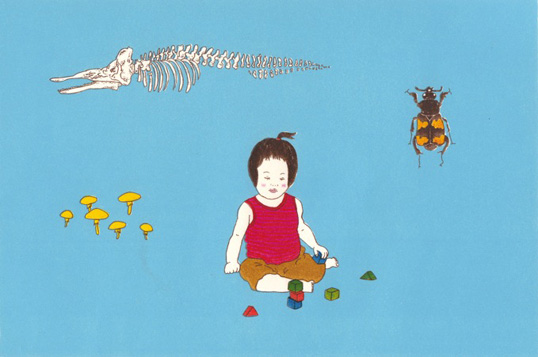

Their dictionary definitions hardly shed an adequate light on the mystery of either life or death. As a child I would often sit and watch dead insects. Or I would kill an ant to observe the difference between the living ant and the dead. I see now that I tried to probe the secret of life with my child's mind.

"Do you have a clear conception of what life is, and how it originated?" I ask of Theo.

"That you will have to ask Hugo Hattingh," Theo says.

"Will he know?"

"He will know, I presume. He should know how life first originated."

"What kind of man is he?" I ask.

Theo Verwey makes an odd little gesture with his head and shoulders. Disparaging, dismissive? I cannot say.

"I don't know him," he says. "Have you started to alphabetise the cards?"

No, I have not. I glance through the cards in my hand. On the greater majority of these cards are words formed with or containing dood (both death and dead). Often descriptive, often to indicate the intensive form "unto death"—to the utmost. Doodaf (tired unto death), doodbabbel (babble to death), doodjakker (gambol or frolic to death).

"Doodlukas?"

"Regional. Dead innocent."

"Nice," I say.

Doodluters as a variant of doodluiters (blandly innocent or unconcerned), I read, doodmoor (murder, torture or strain to death), doodsjordaan (crossing the river Jordan as a metaphor for death), doodsmare (tidings of death), doodswind (wind bearing death), doodswym (total unconsciousness), doodboek (register of deaths), doodbaar (death bier), doodbus (death urn), dooddag (day of death), doodeens (agreeing completely), doodellendig (miserable to death), doodgaan-en-weer-opstaan (die-and-get-up-again, aromatic shrub Myrothamnus flabellifolia—so called because it appears dead in dry times but revives after rain), doodgaanskaap (sheep dying from causes other than slaughtering), doodgaanvleis (flesh of animal that has not been slaughtered), doodgeboorte (stillbirth), doodgegooi (very much in love; literally thrown dead), doodgeld (money paid out at death), doodgetroos (resigned unto death), doodgewaan (mistakenly assumed dead), doodgooier (heavy dumpling, or irrefutable argument), doodgrawer (grave-digger, or beetle of the genus Necrophorus), doodhouergoggatjie (descriptive name for any of various dark beetles of family Elateridae that keeps deathly still as self-protection), doodhoumetode (method by which an animal mimics death).

"They are endless," I remark, "the words formed with death."

"There are many interesting words," Theo says, "but a large number of them have been lost."

"The world is changing," I say. "We don't relate to death as intimately any more. I have never seen a winding sheet. Or felt the wind of death blow. Actually the mere thought of it makes me shiver a little."

Theo smiles. "The wind of death, yes. An unpleasant thought." "An indecent thought," I say. He smiles. I continue looking through the cards. Doodkiskleed (black cloth covering a coffin), doodkisvoete (feet as large as coffins), doodknies (to waste away by continual moping), doodlallie.

"Doodlallie!" I say. "Where does that come from?" "Very prosperous. A regional word." Some of these unusual combinations I have not encountered before.

"Doodop?" "Totally exhausted."

Doodsbekerswam (also duiwelsbrood—devil's bread, poisonous mushroom Amanita phalloides), I read. Doodsbenouenis (distress unto death), doodsdal (valley of death), doodseën (blessing for the deceased), doodsgekla (moaning associated with death), doodsgraad (degree of death).

"Degree of death. As if death has degrees."

"The degree of heat or cold above or below which protoplasmic life can't exist."

"Protoplasmic life," I say. "Would that be the first, most basic form of life?"

"Ask Hattingh that as well," Theo says.

"Would that be the primal slime?"

"It could be that, yes."

Doodshemp (shroud), doodshuis (house of death), doodsjaar (year of death), doodskamer (room of dying or death), doodsklok (death knell), doodskloppertjie (little knocker of death—deathwatch beetle, family Anobiidae), doodskopaap (death's-head monkey), doodsvlek (any one of the coloured spots found on a body twelve or more hours after death), doodsvuur (ignis fatuus: foolish fire, because of its erratic movement).

"I clothe myself in my shroud, my shirt of death, lie down in the room of death at the appointed hour and hark the death knell tolling," I say.

Theo Verwey smiles.

Doodsrilling (shudder as if caused by death; fear of death), doodsteken (sign of approaching death; in memoriam sign), doodvis (to fish to death). Doodtuur or doodstaar (gaze to death).

"Doodtuur," I say. "A strange word."

"To gaze yourself to death at what is inevitable, for example."

"Like the hour of death," I say.

"Like the hour of death," he says.

"To fish to death I also find interesting. To think a stretch of water can be fished to death."

"Yes," he says. "A particularly effective combination."

I ask about the origin of the word dood.

"Probably from the Middle High German Tod, the Old High German Tot, from the Gothic daupus, of which the letter p is pronounced like the English th—probably based on the Germanic dau," he says. "Compare the Old Norse form deyja, to die."

I would like to ask him how he feels about death, now that we are covering the terrain of death so intensively. But it is too intimate a question. Dead intimate. As intimate as death. Intimate to death.

Highly improbable that we will ever know each other that well.

I continue looking through the cards. Dader and daderes (male and female doer, perpetrator). (Theo Verwey and I? And in what context would that be?) Dadedrang (the urge to do deeds). Daarstraks (obsolete for a moment ago), dampig (vaporous; steamy—after the joys of love?). Dries (archaic for audacious), dageraad (archaic for daybreak; Chrysoblephus cristiceps, daggerhead fish).

"Dactylomancy," I say, "you probably know . . ."

"Divination from the fingers," he says, "from daktilo, meaning finger or toe, as in dactyloscopy."

"Looking at fingerprints," I say.

"For purposes of identification," he says. "Based on the fact that no two persons have the same skin patterning on their fingers—and that this pattern remains unchanged for life."

*

On Friday morning Theo and I listen to Cimarosa. Andrew Riddle is the conductor, Theo says. At first I suspect he is pulling my leg. Riddle, as in riddle? I ask. Yes, as in riddle. Riddle left the London Symphony Orchestra to join the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Theo says, and succeeded in getting it back on its feet again.

The music hardly speaks to me this morning. I bend over my cards. Where should I begin? I have urgent matters on my mind, urgent issues for which I cannot find suitable words.

For a while we work side by side in silence.

I am busy with the word dool (roam, rove or wander). Doolgang (labyrinth). The cavities in the inner ear, hollowed out of the substance of the bone, are called the osseous labyrinth. The figurative meaning of doolgang is an errant way: the labyrinths, warrens or networks of the criminal's life. Error is from the Latin errare—to stray. Ronddool (rove, or roam about). Spiritually or morally on the wrong track; to deviate from the way of virtue.

"What do you understand by the virtuous way?" I ask Theo. He raises his eyebrows enquiringly.

"Virtue is the tendency to what is good, and the virtuous way is a metaphor for a life in which the good is pursued," he says. He has clear eyes. He is impeccably polite. His gaze rests on me evenly—without curiosity or demand. That does not prevent me from watching him closely, from pointedly focusing my attention on him. Do I wish to provoke him? Besides his interest in words, he has a great appreciation for music. I have no objection to listening to his music with him. Here, too, I can learn from him.

"Labyrinth, or maze, I find a beautiful word," I say. "It speaks to my imagination. It is poetic, it has resonance, I can visualise it. But I have difficulty with the virtuous way—as a concept it means little to me."

He nods politely. "As a concept and as an expression it has probably long since lost its validity," he says. He gazes reflectively in front of him for a while, before returning to his work.

"How did virtue become deug?" I ask.

"Virtue comes via Latin to the Old French vertueux; deug is of Germanic origin," he says (without looking up from his work), "from the Dutch deugen, from the Middle Dutch dogen." He is also a discerning man, I have noticed. He likes beautiful things. I have seen him unobtrusively lift a cup to look at the name underneath, and turn a teaspoon to check the hallmark. I noticed that the day Sailor treated us to cake at teatime. Sailor had brought along his own tea service, teaspoons and cake forks. No half measures for Sailor—only the best for him, Sof remarked to me.

Doolhof, I read. Maze. Where one cannot find one's way; place where one can easily get lost; bewildering network; labyrinth. The figurative meaning of the word is a complex situation or set of circumstances, in which it is difficult to follow the right way; a situation that makes no sense. Anatomically the word refers to the passages and spaces in the temporal bone of the skull, where the senses of balance and hearing are situated.

Deug and deugdelik. Virtue and virtuous. I see Theo Verwey as a virtuous man—a considerate husband and a loving father. He is reserved. He keeps things to himself. What he holds back, I do not know. I have my own assumptions about his inner life. I imagine it to be as ordered, as filed as his extended card system. I would be very surprised if I were to learn that he is given to excess. This is a man in whom the will—or the virtuous impulse—keeps the appetite, the pleasure-seeking instance, thoroughly under control. This is how I read him. I may be wrong.

*

I sit with the cards in my hand. We are still busy with the letter D. Dorskuur—cure brought about by restriction of fluid intake. Dorsnood. Suffering from the throes of thirst? I ask. Similar to other less commonly used word combinations like dorsbrand (burning caused by thirst), dorsdood (death from thirst), dorspyn (pain caused by thirst), Theo explains. Shall we go and have a drink? I ask. (Theo smiles.) Dos (decked out). (How charming he looks this morning, decked out—uitgedos—in that fine, cream silk shirt.) "Gedos in die drag van die dodekleed," Leipoldt says. Decked out in the apparel of the shroud. Doteer (donate). Douig (dewy)—not a word particularly suited to this province. Douboog (rain- bow formed by dew), doubos (dew bush—word used in West Griqualand for the shrub Cadaba termitaria), doubraam (bramble bush of which the fruit is covered with a thin waxy layer). The many word combinations formed with draad (wire), with draag (variant of dra—carry) and with draai (turn). Who would have thought, I say to Theo, that simple words like these could be the basis for so many combinations? Draaihaar (regional word for hair crown). Has it been your experience as well that people with many crowns in their hair are unusually hot-tempered? Theo smiles and shakes his head. Draaihartigheid (disease caused by a bug found in cruciferous plants whereby their leaves turn inward). The word sounds like a character trait, I say, a twisting and turning state of the heart. Theo nods and smiles. Draais (the word used by children when playing marbles, yet sounding so much like a synonym for jags—horny). But it is especially droef (sad) that interests me. Woeful. Indicative of sorrow. Causing grief or accompanying it. Evoking a sombre or doleful mood. Bedroewend—saddening. Also in combination with colours, to indicate that a particular colour is murky or muted and can elicit sadness, sorrowfulness and dejection. Droefwit (mournful white). And droefheid is the condition of being sad, sorrowful or mournful; inclined to dejection, depression and despondency; something gloomy, cheerless and downcast, as opposed to joy. Is that all? I think. So few words for an emotion with so many shades? The complete colour spectrum—from droefwit (mournful white) to droefswart (mournful black), from droefpers (mournful purple) to droefrooi (mournful red). (Droeforanje, droefblanje, droefblou—mournful orange, mournful white, mournful blue.)