I was stunned. I felt like I’d gone back half a century to when we kids used to run through the paddies and the hills chasing down the flyers we called ppira that spewed out of the sky, glittering in the sun, from the aircraft that frequently flew overhead. Not that we had a purpose for these fliers filled with crude words and illustrations, stressing the importance of anti-communism and urging us to report North Korean spies. Instead, merely getting our hands on them was our most thrilling sport. The boy who collected the most was the champion. It was no big deal if in the process of collecting them you emerged bloody from a close encounter with a thorn bush or a barbed-wire fence.

I felt a rush of blood to my brain and fell into a funk. Forty or fifty years ago it was North Korean spies, and now it’s drones, both of them elusive, inscrutable entities that oppress us. The only advance the two Koreas have to show for themselves is scientific. Otherwise they’re moving in separate directions while continuing to train weapons at each other. No wonder South Korea’s suicide rate is tops among OECD countries for eight years running—what with the chaotic last years of the Chosŏn era, occupation by Japan, division into two Koreas, the fratricidal Korean War, armistice, military dictatorship, and the lack of a formal peace treaty. Add to this 250 kilometers of barbed-wire fencing along the demilitarized zone and you feel you’re still living in a prisoner-of-war camp enclosed by barbed wire. How can you retain your sanity? The tension has lasted too long, disabling us body and soul.

I felt just then that we were back in the Kŏje Island POW camp. Unlike Auschwitz, whose prisoners must have been swept with fear at the prospect of one day being ushered to the showers and gassed, in the Kŏje camp you would fall asleep on your shabby cot with no guarantee you’d survive the night. Sleep was a brief respite—who knew when the war might flare up again? What was worse, the enemy were hidden among us, their identity concealed. To survive, our side had to kill the Northerners. And because we had to kill them, they had to kill us, the Southerners. We became their enemies, but because we didn’t know who they were, we soon became our own enemies.

Leaflet in hand, I trudged down the hill. I felt dejected and helpless, like a lonely POW unable to return to the North or the South, stuck in a narrow corridor between lines of barbed wire.

*

I was drafted into the People’s Army in Haeju, Hwanghae Province. I was nineteen years old, recently graduated from high school and preparing to teach at a grade school. After two weeks of training with other conscripts from Haeju I was thrown into battle.

Because I was clumsy with weapons I ended up in a unit that cleared barbed wire near the front lines. Where possible we blew up the wire fencing, otherwise we made a human bridge, spreading a blanket over it then lying face down in our thick layers of quilted garments so our comrades could hop across on our backs. Protecting the face was a special challenge, and the best we could do was use a protective covering of thick fabric for the head down to the neck and bury our head between our arms. In the process we were poked and scratched by the barbs, but of course this couldn’t compare with the injuries sustained by our comrades in other units. My height worked to my advantage and I became a hero of sorts—the others got to declaring I’d soon get a medal.

The problem was, we had to clear barbed wire not just on the attack but also when retreating. So all the way to Waegwan I was prone with my head facing south, but after our main force took a critical hit in the Battle of Tabu-dong and our lines of retreat were cut off by the Inch’ŏn landing, I was more often prone to the north. South-facing, my downtrodden body and I had time to brace up after the troops made their crossing. But on the retreat I had to bring up the rear, floundering after the others as best I could. And even with the blanket and my quilted clothing it was never easy to navigate barbed wire all by myself.

In the end I got hung up on barbed wire somewhere near Ch’unch’ŏn and was captured by the Yankees. God only knows how many soldiers had crossed over me, the human bridge, but then all was still and I tried to get up but couldn’t. All I could do was lift my head to look around, and that barely. I screamed but heard no response. Only then did I become aware of how much my chest and limbs hurt. Trampled, trodden, and walked over, my quilted clothing had been flattened and it seemed the barbs of the fencing had penetrated blanket, lining, and filling and hooked onto my flesh. What if the coyotes started ripping and tearing at my feet? I suppose I should be thankful the surroundings were littered with bodies the beasts could have feasted on instead.

The sun went down and a hazy moon rose and I started crying like a baby. That’s when the Yankees showed up. I must have looked like a dried pollack strung through its gills on a line because they burst into laughter. Then they poked me with their carbines and stuck a flashlight in my face. I howled like a beast caught in a trap, and they howled in glee.

Swollen all over from barbed-wire punctures, I needed a month’s treatment with antibiotics from the Yankee medics. Lucky me, I didn’t develop an infection. Upon discharge from their field clinic I was transferred from one POW camp to another, arriving at Kŏje Island aboard a US Navy tank-landing ship in March 1951 . . .

*

The only person I was close to in the camp was a P’yŏngyang native called Reverend Chang. He came from a family that had been Christian for generations, and during his training at a seminary run by an American missionary he’d volunteered for the People’s Army in an attempt to shield his family from the Communist Party’s oppressive policies toward Christianity. So everyone referred to him as a minister, even though he hadn’t yet been ordained. He likely knew I’d been saved by the Yankee chaplain from a probable death, and he was friendly to me from the start. I didn’t dislike him, but had always felt I couldn’t bridge the gap between me and the god he believed in.

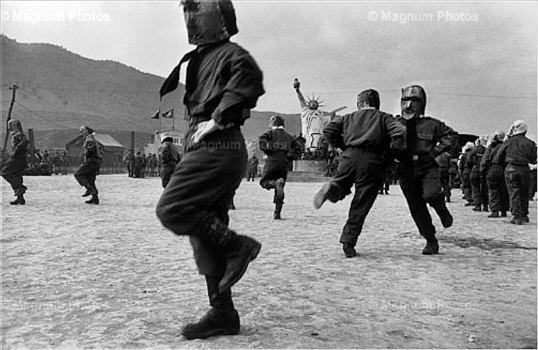

On a warm and unbelievably calm day, so balmy that beggars might wash their clothing, as the saying goes, we did our laundry and hung it to dry on the barbed-wire fencing. That’s what dismembered bodies must look like, I told myself, struck by the sight of the sodden clothing strung all over the wire. Just then I noticed a handsome young blond-haired Westerner on the other side of the fence. He was photographing us. I wanted to smile for him, but instead I gave him a glare, keeping my hands in my pockets. Impassive, he looked me in the eye, then flashed a grin before ambling off into the distance.

Photograph by Werner Bischof

Photograph by Werner Bischof“As long as we’re stuck in this camp,” I asked Reverend Chang, “isn’t there something we could be doing?”

“Well, I suppose we could try dancing? Beats killing each other. And it’s fun to watch people dance.”

“That’s a great idea. But there are all kinds of dances?”

“Right, and if we form one big group and do our lively traditional dances with our legs lifting and our arms flailing around, we’ll end up spooking the Yankee soldiers, don’t you think? Better if we’re moving in some kind of orderly fashion. I bet square dancing would work. I learned it from the missionaries at the seminary. It’s simple but it keeps you on the move. The basic idea is to pair up and spin around in circles. Supposedly it’s a dance that symbolizes the frontier spirit in the American West.”

The next moment he had locked his arm in mine and we were spinning in a circle. But before we’d completed our second rotation our feet got tangled and we fell. Lying on the ice-cold ground, we burst out laughing. Maybe he was right. I couldn’t come up with a better idea, and for all I knew, dancing might make this hell of ours a bit more tolerable.

That same day he began teaching the prisoners to square-dance. At first, most of them found the dance steps embarrassing and slunk off to their tents. But Reverend Chang and I put our powers of persuasion to work and the number of dancers gradually increased. The majority were anti-communist, but we didn’t ignore the fact that some pro-communist moles were among them. Both sides deployed all possible means and tactics to expand their ranks and gather useful information. In that sense, dancing might be utilized to eliminate an important figure on the opposite side, or an inadvertent collision between dancers could lead to a knife-wielding brawl.

Reverend Chang’s ingenious idea of wearing hoods arose from these considerations. Through a special request to the camp workshop he had thirty-three of them made. They looked crude and ugly, but this wasn’t, after all, a fashion show. In no time the dancers had improved to the point where they were ready to flash their moves in public. We were all set.

Reverend Chang put out a call for some fifty dancers and selected the first twenty to show up. I was one of them. Our first order of business was to remove from our clothing any mark or tag that could reveal our identity. In the process three of us had to change into neutral clothing belonging to others. And then one by one we went behind the prisoner tents to the pup tent that Reverend Chang called the “hood room.” There we each picked out a hood and emerged wearing it, in effect becoming a different person. I didn’t know you, you didn’t know me, and we all became one.

Accompanied by martial music, we formed a circle in the middle of the field. The music stopped; the camp band was ready for us. They started in again. “Turkey in the Straw.” I felt I’d been on a long, high-stakes journey at the end of which lay my survival. And here I was at the end of the journey, hooded, arm in arm with my partner, and spinning in a circle.

I was huffing and puffing. My breath grew cold beneath the hood, my face stung.

I remembered hearing that at Auschwitz music was performed from early morning to late at night. It was a grand attempt at deception, the beautiful melodies muffling the screams from the gas chambers and numbing the living to an identical fate.

Perhaps our square dance too was nothing but a theatrical ploy to muffle the cries of people dying somewhere at this instant, and to numb the living to their inevitable death—a thought that made the cheerful tune we were now hearing sound like “The Devil’s Trill.”

But this man whose arm was locked with mine was no ploy. I felt his body heat, smelled his body odor, and knew then he was a human being just like me. What could be more genuine than a feeling that powerful?

Swept with an urge to embrace him, I took him in my arms and held him tight. Startled, he tried to push me away. I wouldn’t let go and tried to pull him back. And to my surprise he let me, and the next thing I knew he was embracing me.

When we are hostile to each other we turn into barbed-wire death traps. Even slight contact can leave a scar. To get outside the barbed wire we had to embrace each other, there was no other way. We had to embrace the man himself, bereft of blanket and quilted garment. We had to blunt the barbs with our blood and our scars.

Holding tight to each other, so tight our feet dragged along the ground, we slowly spun. We were no longer square-dancing but had released each other and broken into a traditional mask dance, legs lifting and arms flailing. Did we remove our hoods? I’m not sure. Did the band pause and switch to a traditional tune? That too I’m not sure of. Did all the others out on the field join our festive mask dance? I can’t tell you that either. Well now, when would this dance come to an end? Better yet, couldn’t it continue forever? Everything existing on this Earth of ours had been sucked into the moment of our dancing.