Over the years, scholars such as Toril Moi and Michèle Le Dœuff have helped to untangle Beauvoir from Sartre, to treat her as an independent thinker by conducting thorough examinations of her prolific body of work. Kate Kirkpatrick’s brilliant 2019 biography, Becoming Beauvoir: A Life (Bloomsbury), provides a nuanced account of Beauvoir’s life and a rigorous treatment of her intellectual development and originality. Beauvoir scholarship in general is also experiencing a renaissance; the bilingual, interdisciplinary Simone de Beauvoir Studies journal is publishing articles that not only treat Beauvoir’s work in its own right but explore her continuing relevance to our contemporary moment.

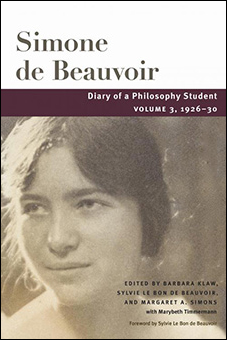

We have new, direct access to Beauvoir’s voice thanks to the incredible efforts of the University of Illinois Press’s Beauvoir Series. In eight volumes, it offers English readers Beauvoir’s assorted philosophical, literary, political, and feminist writings, her wartime diary, and her student diaries. The third volume of the latter is the most recent release, from January of this year. Entitled Diary of a Philosophy Student, it includes three notebooks from 1926 to 1930 that were missing from the previous two volumes. Gallimard released a complete French edition of the diaries—which required years of transcription and editing—in 2008, and this third English volume fills in the gaps of the critical, transformative period of Beauvoir’s life from the ages of eighteen to twenty-two.

The first volume covers Beauvoir’s late teenage years, before she met Sartre, revealing her diverse interests and passions as a student. The second volume shows us a maturing Beauvoir who debates with Sartre and discovers her formative intellectual influences. In the third volume, the predominant theme is love: for her cousin Jacques and then for Sartre; for her friend and confidante Zaza, who tragically dies; for her studies; for life; and for herself. “I have two equally sure and necessary foundations,” she observes, “my own strength and my love.” Within these pages, we learn what she reads, where she goes, what she sees, with whom she spends time. The entries are peppered with quotations, sometimes lengthy, that were impactful to her at the time. These are invaluable resources when tracing Beauvoir’s early philosophical inspirations.

At times, Beauvoir writes with the air of a hopeless romantic, celebrating the joy of everything in her life and her sense of community; at others, she is beset by serious depression and emphasizes a profound feeling of isolation and lack of connection. Sometimes, she has a voracious appetite for reading and a limitless passion for philosophy; other times, she doesn’t feel inspired to read a single word and remarks that “philosophy is a game that becomes boring after a while.” We read about her ambition to take her exams, write a book, and make something of her life.

In contrast to her carefully crafted Mémoires d'une jeune fille rangée (Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter; Gallimard, 1958), which bears the stamp of hindsight, the diaries are immediate and raw. Here, Beauvoir provides a level of detail and a frankness that simply does not exist in the memoir. From a young age, Beauvoir was aware of the blurred boundary between life and fiction. She conceived of her life as a process of narrativization, of the self as an author or an artist: “I create myself. I create my story.” The sense of authorship and authority relative to one’s life is an early articulation of the existentialist commitment to self-creation. In a passage drawn from the new volume, she muses, “perhaps it is through the act alone that the self is posited; and I want myself.” This prioritization of action over thinking became a hallmark of Beauvoir’s philosophy. In an essay from 1948 called “L’existentialisme et la sagesse des nations” (“Existentialism and Popular Wisdom”), she re-articulated her adolescent wisdom: “there is no divorce between philosophy and life. Every living step is a philosophical choice.”

Beauvoir’s equal commitment to love and to self-creation produces a tension between living for others and living for oneself. She frequently expresses a struggle to find “equilibrium” (l’équilibre). Reflecting on her relationship with her cousin Jacques, she writes, “above all I must not live only in function of him. This is what threatens every woman in love: she will abandon in herself everything that is not immediately necessary to the other, she will content herself with being the same as he desires.” This is a startlingly astute observation to have at age eighteen and prefigures her future remarks, in The Second Sex, about women’s participation in oppressive mythologies. She also proposes an idea for a novel based on the premise that “when desire is finally realized, desire has died,” from the point of view of a man trying to both realize and preserve his desires. She did go on to explore the fleetingness of desire, but from the perspective of three women abandoned by the men in their lives, in her 1967 novel La Femme rompue (The Woman Destroyed; Gallimard, 1967). The adolescent Beauvoir, however, at times subordinated her academic pursuits: “who could have told me that I would be, not an intellectual, but rather a woman in love?” Decades later, in The Second Sex, Beauvoir would devote a chapter to “The Woman in Love,” painting a critical portrait of the lack of reciprocity between the sexes.

Due to the private nature of the diaries, they reveal a window into not only Beauvoir’s inner life, but also events that she edited out, glossed over, or rewrote in her memoirs. One of the most significant revelations concerns the early days of her relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre, whom she met at age twenty-one. Despite Beauvoir’s infatuation with the charming young philosopher, she expresses ambivalence and even concern about her relationship with him in the diaries. “My love for Sartre is almost worrisome,” she confesses. “Sartre doesn’t understand anything about this love; that it is the love and not these games of love or these passionate romance novels into which he invites me.” She knows that there is a disparity in their feelings but throws herself headlong into the relationship. Unlike her chaste love for Jacques, her desire for Sartre strips away her previous disgust for the body. But this newfound intimacy causes her concern: “I was taken aback by this very new fever, and fearful of its violence and all that it predicts of a not very appealing suffering.”

Unfortunately, Beauvoir’s premonition was correct. In a series of scattered entries from October 1930 that begin with the description, “days of insane happiness,” she alludes to the loss of her virginity to Sartre. Her reflections are ambiguous, though her feelings of sadness and regret are evident. There seems to have been a profound misunderstanding between the two; Sartre mistook her willingness for sexual desire when it was a marker of her trust in him. Shortly after this episode, Beauvoir pledges herself to Sartre: “I am his as much as he wants, in all the ways that he wants.” But as their relationship continues, there are moments when she seems to be triggered by the events of October. One night, when they are together, she admits, “an unknown caress scared me, but without his suspecting this brief panic that I quickly overcame.” Physical intimacy seems to make Beauvoir not just uncomfortable, but terrified. Is this a trauma response?

These passages from the diaries are heartbreaking to read and reveal the volatile nature of the early days of her and Sartre’s relationship. Describing their infamous “pact” to be each other’s main loves but still engage in other affairs, Beauvoir writes, “I debate with myself. I am profoundly happy because I know that such is contingent life, and after all it is what I have chosen, but there is a sadness, an anxiety that I cannot surmount . . . sadness of the body and sadness of the heart.” As in the passage describing her loss of virginity, Beauvoir emphasizes her freedom of choice in situations that make her sad. She knows that she will get hurt but is careful not to let on: “I lied to him every time that I was sad, which is rare, but still too often; and I hid from him the magnitude of my indifference, which makes him say, ‘It’s too easy.’” She creates an effortless facade for Sartre, who reprimands her for her dependence on him without any awareness of his emotional impact on her. These insights challenge us to reflect anew on the impact of Sartre on her life.

The final notebook in this third volume ends not on a note of despair, but of hope. Beauvoir begins to return to herself in these entries from 1930: “I want a sensational life,” she writes. The promise of redemption begins to emerge: “I must take care of myself, live for myself and through myself as in the past, but with more intelligence and more passion - and a great purity. I have to will this, will this, and will this. If I will it, I am saved.” Indeed, though she remained loyal to Sartre, Beauvoir forged her own thriving career and lived a full life that was not entirely reliant or dependent on him. It can be tempting to see her as a victim, as entrapped in the patriarchal systems she so vehemently decried in her work, or even as a hypocrite, as someone who didn’t practice the feminism she preached, but neither does justice to the complexity of her life and work.

Having access to the student diaries is a gift for English readers who want more in-depth access to the thoughts and emotions of the precocious, fiercely intelligent, and caring young woman who would go on to write one of the most famous books in the feminist canon. In these notebooks, we see her nascent intellectual positions emerging alongside her reflections on love, friendship, and meaning. Beauvoir can come across as a somewhat imperious figure, but the diaries humanize her, revealing the vulnerability and unfiltered passion of her younger self working through intellectual questions alongside personal challenges. Beauvoir’s French is a joy to read, and the translator, Barbara Klaw, has done a remarkable job of capturing its vividness and richness, rendering it accessible in English but removing none of its intricacy. This stands in stark contrast to the first English edition of The Second Sex from the spring of 1953, in which the translator, Howard M. Parshley, deleted fifteen percent of Beauvoir’s words and missed her philosophical nuances in French. He felt justified in his edits because “Mlle de Beauvoir’s book is, after all, on woman, not on philosophy.” Beauvoir’s public and private works serve as a direct challenge to and negation of this sentiment, and the recently translated student diaries show us that we cannot fully separate the personal and the philosophical.