The cat lady is a cautionary tale. A story that chimes in your head when you leave a philandering boyfriend or a job that prematurely greys your hair. There are no cat gentlemen. That’s not to say there aren’t lonely men straying the pages of English literature. Jay Gatsby could’ve been a cat gentleman. Instead, he threw parties that camouflaged just how lonely he was. Holden Caulfield hid behind his cynicism, and in a big city like New York, everyone is lonely, not to mention that Holden Caufield was a teenager. The only exception, perhaps, is Robinson Crusoe, who did have cats to keep him company in his isolation. But he doesn’t fit the bill either. He builds makeshift furniture—he’s self-reliant and not piqued about having to be—and his situation is outside his control, unlike the slovenly cat lady, who chooses her loneliness despite all the warnings she heard when she was young. In Crusoe, you can find inspiration, or at least you’re supposed to. But when you run into the unnamed woman in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” anxiety, fear, and rage envelop you.

Both characters are isolated from society. Crusoe is cast away on an island, and the woman is locked in a room. As Crusoe hallucinates companions, the woman descends into obsessive madness. Neither character chooses their isolated situation—Crusoe is shipwrecked, while the woman’s husband forces her into the room to “recuperate.” However, what’s different about the characters is that Crusoe is an adventurer who happens to go mad, while the woman in Gilman’s story is a patient. If anything, you pity her. Even if you interpret her “madness” as a form of defiance, it’s still hard to take heart in her state of affairs. Within a society that often silences and pathologizes women’s voices, a woman’s madness becomes a threat to be contained. It challenges the very order that seeks to control her. Her madness—literally hers—must be feared.

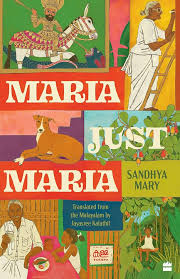

While Gilman’s character seems to succumb to despair in her isolation, Sandhya Mary flips this idea of inevitable suffering in Maria, Just Maria by granting Maria, her protagonist, agency and even a sense of amusement in her solitary life. The novel begins with a dream. Maria has woken up in a mental asylum and tells us she’d like to write a book. In the novel’s non-linear narrative, however, we soon find ourselves transported back to Maria’s childhood, a time seemingly defined by visceral experiences rather than introspective pursuits. This younger Maria, who finds kinship with stray dogs and revels in her unconventional upbringing, embodies a different kind of freedom than the one sought by her older, asylum-bound self. The act of writing, of imposing order and meaning through language, seems far less appealing to this younger Maria than, say, the wild responsibility of raising an elephant. Maria grows up with her grandparents and other relatives in their ancestral home, Kottarathil Veedu. This period is depicted through her interactions with Chandippatti, a talking dog, her grandfather Geevarghese, and her dread of holiday gatherings with the rest of her immediate family.

Maria, Just Maria is constructed from notes that Mary originally wrote in English, which she then used to create a loose narrative that became a novel she wrote in Malayalam, and which was translated back into English by Jayasree Kalathil. While incidental, the process of translation and re-translation seems integral to the novel’s exploration of voice, identity, and the fluid nature of memory itself. The novel’s multiple linguistic layers inform its very structure, prompting the reader to consider what is gained and what is potentially lost in the passage between languages. Some characters flicker in and out of focus, their stories at times fragmented or incomplete. It’s as if these characters, like trinkets that once sparkled, have been momentarily misplaced in the novel’s own journey between tongues, leaving behind a residue of their presence, even in their absence.

Maria’s aunt Neena, for instance, likes her solitude so much that her husband and his family are embarrassed by her self-assurance and surprised at her kindness towards her husband’s lover, a “servant woman” named Mollama. Then there is—I’m using the same phrase that Mary often uses to introduce another one of her trinket characters—Mathachan, who considers himself to be a “lucky man[,] much luckier than Geevarghese” because of his internecine but platonic relationship with Maria’s grandmother. Sometimes, Mary introduces characters and does not tell us much about them until chapters later. It’s disorienting to keep up with them, but only if you attempt to. Reading the novel is like becoming a hoarder of details. The narrative structure, precariously balanced like a game of jenga, makes it difficult to discard any character or storyline for fear that even the smallest piece might hold the key to a larger understanding. Mary justifies the episodic nature of the novel in her conversation with Kalathil in the postscript, “ . . . after all, it’s written by Maria,” underlining how fidelity to the character necessitates splintering all the conventions of form. The rationale behind this fractured narrative isn’t immediately evident, not unless they’re willing to listen to Maria digress like I was.

Maria has one consistent desire: to be “just” Maria, not bridled by the expectations that she should work—which she hated during her time as an editor—or be married—which she experimented with and didn’t enjoy. When her husband says that being occasionally unhappy in a relationship is just "how life is" and must be accepted, she says, “Another life should be possible.” The lack of an imagined alternative doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. Maria, of course, wants to “work” but not in the way expected of her—she wants to work in a world of economic justice, where her identity wouldn’t invite incredulity that it currently does, where work wouldn’t define her, where she would be “just” Maria, not Maria the editor, Maria the madwoman, or Maria the orphan, as her siblings introduce her to their schoolmates. The way she lives seems to indicate that there is more to life than merely resigning oneself to the inevitability of unfulfillment.

This liberating idea fades when the reader is met with this shard of logic: Maria can exist the way she does because everyone else sustains her. Her friends pay for boarding and food, and her brother pays for her eventual stay in an asylum. This can be unsatisfying for the readers who are looking for more than a stilted escapism when the protagonist is obviously painting a fantasy for herself. There is no room to suspend your disbelief. But I wasn’t too bothered because Kalathil’s translation cosseted me. Sometimes, you enjoy a book for its form. I enjoyed this book for how it is translated.

When Maria refuses a snack from her mother, who is as good as a stranger to her, she says, “No, thank you,” and her brother imitates her, saying, “Nyo, thyankyu,” proceeding along with her two sisters to bully her in “sing-song voices”. Although she’s mocked for her colloquial accent, Maria assumes it’s the fact that she is polite at her own house that invites derision. She knows she’s the butt of the joke, but not why. Kalathil lets the reader in on the heart-breaking realization that Maria’s siblings’ mockery is rooted in a deeper, more personal discomfort with her politeness, which they see as an affectation. Kalathil also splits open for the reader the humour that laces Mary’s storytelling. When Anna, Maria’s grandaunt, asks for rice water (“kanjivellam” in Malayalam), she pronounces it as “kanjaalam,” swallowing a few syllables, prompting everyone to dub her "Kanjaalam valyamma” (literally, “Grandaunt Kanjaalam”). Kalathil ensures the reader understands the wordplay and humour behind this anecdote by nestling the correct pronunciation and the meaning of the word into the narrative, choosing not to relegate the linguistic mix-up to a dull footnote, bolstering the characters’ absurdity.

Kalathil isn’t interested in hiding the fact that the novel is a translation. In sentences like “And, of course, at school where it was a festival of thrashing,” you know the English is a costume for the Malayalam. The English sits a little oddly in it. In the postscript, Kalathil talks about keeping many of the words and phrases that Maria coins throughout the novel: “I’ve chosen to retain these as they are because, well, the idea that others learn words and make them part of their speech is how a language acquires new words.” Language, for Maria, isn’t static—neither is it for the novel she has found herself in.

When Maria craves a specific brand of ice cream she used to eat as a child, Joy Ice Cream, Aravind hunts down a shop that sells it and orders her all the flavours. As she eats the ice cream, she says it doesn’t taste as good as it used to, and Aravind responds by nicknaming her the “Cat with the Bad Attitude.” This nickname comes from a Russian folktale where a cat in a drawing compels the little girl who drew it to draw it many other things, testing her patience. Eventually, the cat tricks her into drawing a window through which it walks out.

Maria has all the trappings of a cat lady: lonely because she fails to understand the people around her who understand each other well, isolated because she’s in a mental asylum, misunderstood because she dares to defy the status quo, without realizing the consequences, and impolite because she almost always says what she feels. The novel ends on a sad note: “Poor Maria”, we think, but this is not a lamentation for the choices that Maria made; it’s an accusation against the world for refusing to accept Maria’s childlike wonderment and idealistic outlook that it so desperately needs. The cat lady in this novel—who in fact has a strong affinity to dogs—openly indulges in her penchant for an alternative life, even if she doesn’t know what that looks like. In her solitude, Maria pays little mind to judgements about her unusual lifestyle. Her “madness” is her honesty and her ability to embrace it. Her perceived failure is the failure of those around her, mirroring how society deals with individuals who challenge its norms. It is our failure.