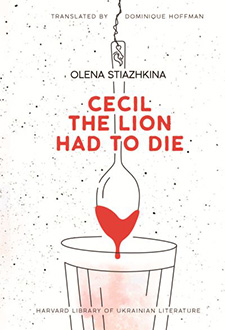

The story of Cecil the Lion blazed brightly in the news cycle and was almost immediately forgotten. But his death is given new meaning in Staizhkina’s novel, Cecil the Lion Had to Die, as a metaphor for the war in Ukraine, a symbol of senseless tragedy, and the transience of human attention.

The book, published first in Ukraine in 2021, and now in Dominique Hoffman’s deft English translation, is partially a rebuke. Why didn’t bombs falling on Ukrainian cities, the forced displacement of over a million Ukrainians, and the deaths and disappearances of countless others surpass Cecil the Lion as an event worthy of international attention?

Instead of Cecil, Stiazhkina directs our attention to the lives of regular, albeit fictional, Ukrainians, from her hometown of Donetsk, which has been under Russian occupation since 2015. The book reads like a family photo album. Each chapter is a snapshot, titled with a character and date, just like the caption of a photograph. Through this series of non-sequential pictures, Stiazhkina interweaves the stories of twelve characters over the course of thirty-four years. Each of them must grapple in their own way with the question of how to live in a globalized world, where the heavy constraints of Soviet rule have been lifted and replaced with a boundless freedom in which no one quite knows the rules of the game.

The first photo, taken for the local newspaper, features the whole cast of characters: Andrey and Tanya Nefydov and their new son Lyosha, single mom Angelina and her new daughter Thelma, recently widowed Bogdan and his son Ernest, and the Lishkes—Petro, Maria, and baby Halyna. The year is 1986, the same year as the Chernobyl disaster and the centenary of the death of German Communist Ernst Thälmann. To honor the anniversary, Heinrich Fink, a local Soviet functionary, concocts an idea to name a child (or children) after Thälmann in the name of Soviet-German friendship, but the event doesn’t happen as planned. The photo features all four newly minted babies, their six parents, the Soviet official himself, and Babá, one of the local spirits. The ritual forges the four families into one. Willingly or otherwise, they are “foisted upon one another by the turbulent political fantasy” of the Vice Chairman of the District Executive Party Committee, who from then on is known as Grandpa Fink.

Two of the babies, Ernest and Thelma, are loosely named after Thälmann. The other two, Halyna and Lyosha, are given names with no historical baggage. But by the time these children are school-aged (another photograph on their first day), Soviet practices such as naming children after dead Communists are things of the past, and a new world has been ushered in with none of the ideological constraints or rigid structures of life in the Soviet Union. The kids experience a childhood saturated with Kinder Egg toys, pirated seasons of Spongebob, and dreams of special pink Cadillacs for Ukrainian mothers who sell enough Mary Kay. Gradually, accidents in coal mines, violent encounters with gangsters, a holiday in Milan, teenage love affairs, and grown-up infidelities leave parents and children feeling like the rails have come off, that the writing is on the wall of a Khrushchev-era apartment building.

In Stiazhkina’s view, to be born in Donetsk in 1986, to grow up in a part of the world so ravaged by violence, is to have been issued a ticket on the Titanic, fated to sink under the weight of Russian war and occupation. The book is replete with references to the biblical story of Belshezzar’s Feast in which the prophet Daniel (the one who was saved from the lion’s den) foretells the fall of Babylon at the hands of Persian invaders. Like the people of Babylon, the members of these four-families-turned-one have been “weighed, measured, and found wanting,” and now have to contend with their own Russian invasion. Looking back from the third decade of the twentieth century, it feels as though the lives of these four children were doomed from the start.

But there is a fairytale element to the novel that provides a way to break the curse. The characters have two ghostly guardians: Shubin, the coal-mining spirit of Ukrainian folklore, and Babá, a grandmotherly ghost of the Lenin District, who will save your life or burn down the liquor store, depending on her mood. They also have a kind of godfather in their adoptive grandfather, Fink. Fink is a Ukrainian-born ethnic German who grew up in Kazakhstan after his family was forcibly deported by the Soviets. As a child in the postwar Soviet Union he was constantly browbeaten for his German origins. His scheme for naming the children after one of his German heroes is his way of attempting to give them a better life than he had, although implicit in the book is the question of which pair will fare better, the ones named for Thälmann, or the ones unbound by this tie to the totalitarian past.

Fink’s belief in the power of human transformation offers the characters a lifeboat, a way not to go down with a ship that is getting sucked into the Russian whirlpool. The characters are offered a chance to change their circumstances. This could mean overcoming a gambling addiction, being a better parent to the second child than the first (Thelma’s little sister Dina arrives on the scene when the original four kids are already in their twenties), trading cosmetology for a new career as a Ukrainian sniper, or moving to Munich, Kyiv, or Moscow. But it’s not clear if all the characters are willing or able to take advantage of these second chances and the opportunity to redefine themselves.

One tool Stiazhkina uses to signify the characters’ ability to adapt and to take control of their lives is language. In the original, the book is written in both Ukrainian and Russian in near equal proportions. Some chapters—and even conversations—are bilingual. The use of each language is partially temporal, where Russian is the language of before and Ukrainian of after, the dividing line being Russia’s initial invasion of Ukraine in 2014. Language, in this case, is not a sign of a character’s allegiance, but a signifier of transformative potential. The characters who orient themselves around a more constructive future appear primarily in Ukrainian, while those who are mired, for whatever reason, in the past are rendered largely in Russian.

This critical nuance, which is essential for understanding the orientation of each character, would be lost in English translation, were it not for an innovative solution devised by the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. The use of each language is cleverly preserved for the English-speaking reader by the color of the text, black on white page for Ukrainian, and white on black page for Russian. While the color-coding doesn’t match the original text to the letter, it preserves a crucial linguistic distinction without which the texture of the novel would be flattened.

Stiazhkina herself has undergone a similar linguistic and personal metamorphosis, one that she details in her book Ukraine, War, Love: a Donetsk Diary, translated by Anne O. Fisher and published in English by the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute in 2019. Like many other natives of Donetsk, she grew up and built a career speaking and writing in Russian, even winning Russian literary prizes. But this became a source of shame for her in 2014 when Russian troops started their reign of terror in Donetsk. She, like many other writers from the Donbas region, chose to reject Russia’s claim on Russian-speakers and adopt Ukrainian as her language of self-expression. Because Russia has used the trope that it is “defending the rights of Russian speakers” as a pretext for its violent attacks on Eastern Ukraine, for native Russian speakers to write in Ukrainian is to defy Moscow’s attempt to claim them and to assert their own selfhood and nationality.

In some ways, Cecil the Lion Had to Die has much in common with other war novels written by Donbas natives. For example, Volodymyr Rafeyenko’s Mondegreen: Songs About Death and Love, also meditates on the transformative power of the Ukrainian language, particularly for those forcibly displaced by Russian troops. Another common thread is the use of zombie apocalypse or alien invasion imagery to describe the alienation of friends and family members taken in by Russian propaganda. For Tanya, one of the mothers, the transformation into a pro-Russian alien takes place gradually over the course of divorce and remarriage, and she becomes estranged from the rest of the family. This echoes the experience of many Ukrainian families who have been unable to break the spell of Russian propaganda and convince friends and relatives from Russia that Russia has attacked them unprovoked.

While Tanya’s mutation is metaphorical, in Rafeyenko’s The Length of Days: An Urban Ballad (Harvard University Press, 2023) Russian intervention causes several characters to literally turn into massive man-eating insects. These images contribute to the apocalyptic feeling evoked by the Russian invasion and occupation. Stiazhkina’s repeated references to Rembrandt’s painting Belshazzar’s Feast resonates with Stanislav Aseyev’s allusions to the Dutch painter Heironymous Bosch as a way of depicting the hellscapes of war-torn Donetsk.

Throughout the book, the characters of Cecil the Lion Had to Die perpetually struggle to find the right words to express themselves. While one might expect the adoption of a new language to complicate communication, for Stiazhkina this is a kind of homecoming. In an interview with Suspilne, Stiazhkina recounts that as she was leaving the Donbas in 2014, she thought, “If a missile catches us now, how will we know we are home when we regain consciousness? Probably if the doctor or the person who opens our eyes addresses us in Ukrainian, right?”

Since the book’s original publication in 2021, the consequences of Russia’s war for Ukrainian families have only grown more acute. While it was possible in 2015 to lose sight of Ukraine amid the Syrian refugee crises, Charlie Hebdo, the legalization of gay marriage in the United States, and the death of Cecil the Lion, since February 2022, the scale of Russia’s aggression has become too explosive to ignore. “Not seeing Ukraine is a disease,” writes Stiazkhina in her Donetsk Diary. “Ask Viktor Yanukovych what that disease does to you.”

Indeed, Russia has worked hard in its attempt to make Ukraine invisible, to wipe it from the map, to deny the very existence of the Ukrainian language. They have even destroyed the Vivat publishing house, one of the largest in Europe, to prevent books such as this one from reaching its readers. But Ukraine is arguably more alive in the global consciousness than ever before. Stiazhkina joins an all-star list of writers, directors, and leaders who are correcting the record and raising the stories of Ukrainian families above the noise of social media ephemera.

So, too, might be the practice of relentlessly documenting all of life’s precious, bizarre, and tragic moments. Like Cecil, the weddings, birthdays, and baby pictures that we swipe past on social media are ephemeral, consigned to memory almost immediately, lost in the Cloud. Do these moments have meaning? By the end of the book the characters have been “diffused and scattered like spores in the heart of Europe.” Several of them are no longer on speaking terms, for both family and war-related reasons, and they stop taking photographs. But they don’t stop wishing: “The world has become dangerous in ways they never foresaw and they have very few wishes left. One of which is a photo. A photo with everyone. A selfie with Thelma. With Dad. With all the parents. With Ernest and Lyosha. With Grandpa Fink. Get him in the frame, too. A selfie with everyone.”

The novel ends in 2020, but if it had an epilogue, it might show that the transformation of this country at war is far from over. While parts of Eastern Ukraine seem doomed to destruction and Russian occupation, thousands of Ukrainians have taken matters into their own hands, raised arms in defense of their country, and redefined themselves in the Ukrainian language. It’s not clear, even now, if Ukraine will take its place among European nations or if Donetsk will sink like Atlantis. It may be a lost city for now, but Stiazhkina’s characters demonstrate that people don’t have to accept their fates, even those assigned at birth.