Surrealism as a heightened sense of reality is one way of trying to understand war. Another way is to acknowledge the destruction it brings. In the poem “On War,” Makhno writes, “death [ . . . ] is a hole-riddled soldier’s heart, nothing more.” The metaphor doesn’t depart too far from its object. Surrealism and, more generally, poetry’s way of deriving deeper and less immediate meaning from things nonetheless stagger in the face of war.

Does writing war poetry bring any redemption? Perhaps Barskova identifies The Iliad as the first instance of this genre an essay by the philosopher Simone Weil titled, “The Iliad, or, the Poem of Force” (“L’Iliade ou le poème de la force”), published in 1940 after the fall of France and translated into English by James P. Holoka and published by Peter Lang in 2006. Weil defines “force” as: “that which makes a thing of whoever submits to it. Exercised to the extreme, it makes the human being a thing quite literally, that is, a dead body. Someone was there and, the next moment, no one.” According to Weil, the epic poem defines how “force,” or violence and war, turns people into inanimate objects. One idea of what poetry does is that it engenders a heightened sense of reality attuned to less conscious, deeper meaning. Can this different perception of reality work against the reduction of meaning, of animacy itself, that war entails? Poetry often begs a reader to refrain from too quickly assigning meaning and ending the pursuit of meaning. Can this rhetorical purpose work against what “force” does? Can it delay meaning’s dissipation, delay people becoming things? It’s no wonder that surrealist poetry comes after the experience of World War I.

In “1918,” Ostap Slyvynsky, translated by Anton Tenser and Tatyana Filimonova, writes, “all I remember from that war,” and goes on to describe a horse falling off a platform, a scene similar to that of the raid of Vladimir in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film, Andrei Rublev (1966). The speaker of “1918” describes this scene as if they were present, suggesting that the trauma of one hundred years ago is still a source of meaning for a contemporary Ukrainian poet. Ukraine’s history is as entangled with the experience of war as Soviet history is. But the “war to end all wars” was, of course, not the end of war. In fact, it was the beginning of a new kind of warfare, as Barskova describes it, a war of “massive and ‘anonymous’ destruction.” Out of that war came, at least, surrealist poetry. But the reduction of meaning took its toll. In 1940, Weil wrote about how “the force that kills” can even reduce a person without killing them, merely by the fear it produces: “ . . . though breathing still, he is no more than matter; still thinking, he can think no more.” It’s as if force were an infectious disease which either kills a person or makes them view other humans as “no more than matter,” not as living beings. As Yuri Izdryk puts it in “Darkness Invisible,” translated by Boris Dralyuk, “evil has melted away in our world, as ice turns to water / diffused invisibly, like mist in air.”

Poetry must match this infectious reduction—no easy task. Perhaps poetry can mimic how force reduces meaning, like Makhno’s “hole-riddled soldier’s heart, nothing more,” in order to reestablish meaning. Again, according to Weil, that description of reduced meaning is what gives the Iliad its literary appeal. But can depicting “force” and its effect work against “force”? Similar to Theodor Adorno’s assertion about writing poetry after Auschwitz, Anastasia Afanasieva asks an existential question in a Russian poem translated by Kevin Vaughn and Maria Khotimsky: “Can there be poetry after[?]” However, while the translation has the typical inversion of a question in English, and the Russian original uses the interrogative participle “ли” (li), the punctuation following “after” is a colon. In the original, the next four lines are place-names where conflict and death, “force,” had already taken place in Ukraine in 2018. There’s a repetition of that word “after” and then three more place-names, the last two of which are Donetsk and Luhansk (Lugansk in Russian). The next piece of punctuation comes once the poem’s language has taken on the syntax of statement rather than question, suggesting that Anastasieva’s words are also more like an assertion than a question. It’s as if Anastasieva is reminding the reader of what has happened, perhaps in order to resist any all too easy redemption herself. When she writes, “Impossible to speak of anything else, / Talking becomes impossible,” the reader might wonder if anything can work against what the Iliad describes in Weil’s interpretation. Perhaps all a poet or writer can do is to remind a reader of what has happened, keep it within collective consciousness. Perhaps this kind of inventory of the everyday that one loses during war is why, in an excerpt from Anastasieva’s cycle Cold, translated by Katie Farris and Ilya Kaminsky, there is an ever-shortening epistrophe ending with the word “glory,” translated from the Russian word “хвала” (for khvala). As the poem narrows down, Anastasieva writes, “Of a wind, say: / glory.” And later, “To no one, unknown / One blue on white / And quiet that splinters / the winter: / glory.” The tapering of the epistrophe, of the language both visually and in meaning, suggests a breaking down of all that surrounds. Such whimsical analysis can often occur during lockdown because of war or a pandemic. It can comfort, or it can become a ruminating swirl into insanity. If people are becoming things, the things can glorify other things, and this glory can recreate meaning. By glorifying the things of normal, everyday life that “force” takes from us, by turning them into metaphors for war, Anastasieva works against the reduction war engenders.

However, poetry won’t save lives, will it? Weil’s reading of the Iliad did not change any of what happened for the five years after she wrote her essay. Of course, Ukraine knows what happened in those five subsequent years. In the Soviet Union and even post-Soviet Ukraine, The Great Patriotic War remains an open wound. Was there ever reconciliation with the trauma it produced? Kateryna Kalytko asks in a poem translated by Olena Jennings and Oksana Lutsyshyna, “Was everything, everything that happened for a greater good,” using the Ukrainian word “великий,” (velykyi) the same word used for “great” in Great Patriotic War, “or would all the agony cause a tall tree to grow – bleeding / berries, pounding against apartment windows at night?” What has come of the wars that were supposed to end all wars? What was “great” about them? And is this suffering natural?

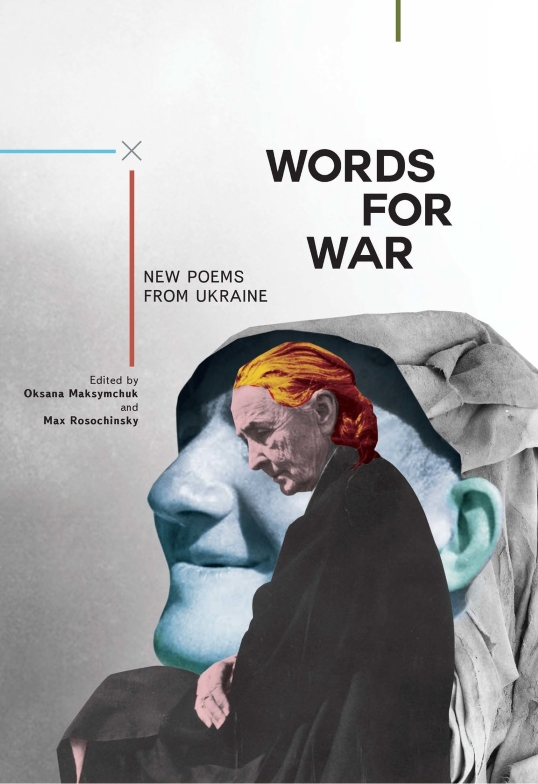

The relationship of the generation that followed the Great Patriotic War to the trauma of that war appears in a poem by Marjana Savka, translated by Sibelan Forrester and Mary Kalyna with Bohdan Pechenyak. Savka writes, “We wrote poems / about love and war, / so long ago / [ . . . ] in the days before we had war.” It sounds like an idyll, the decades after the Great Patriotic War, when war became something always remembered but not necessarily a present reality. It doesn’t sound like metaphors, such as Makhno’s bullet-riddled heart, were included in the poems Savka describes. But Savka’s own poem drops at the end: “What changed, my sister? / Our hot-air balloon / turned into a lead ball. / The metaphor – died.” What sounded like an idyllic romance became real war, sluggish and unmoving in its meaning, which is like the heavy metal out of which bullets are made. The war poetry of Words for War and “poems about love and war” are very different things.

Each instance of “force” appears to need its own specific response. The current invasion of and war against Ukraine is, like the two world wars, different to any previous war since it’s the first time the two largest Slavic, formerly Soviet, countries in Europe are fighting against one another. It’s the first time that many on the battlefield speak the same or a very similar language, curse with the same words. Like Weil’s “force,” this war is destroying Ukraine’s people and structures while also destroying Russia’s military, economy, society, and culture.

It’s also likely many of today’s fighters hadn’t yet been born when the Soviet Union ended. Poems in Words for War reflect that the current war has engaged the children and grandchildren of the post-Great Patriotic War generation. Ukraine’s contemporary poets reflect on this young generation’s experience, as discussed in Kaminsky’s introduction to Words for War, where he mentions Kalytko’s use of a child as a metaphor for war. Indeed, one of the most striking and heartrending aspects of this war is how closely related the two sides are. The way “force” can dehumanize people is its worst effect. It is the absolute opposite of poetry’s heightening of meaning, reducing even children to things. For Kalytko, the process of re-humanization could begin by giving human meaning to war itself.

Similarly, Marianna Kiyanovska, translated by Oksana Maksymchuk, Max Rosochinsky, and Kevin Vaughn, uses the metaphor of a fledgling for death. The speaker feeds death with her own blood. “Don’t go, she pleads, / There’s nothing there. / I too have a soul, she says.” The metaphor of mothering death, of death as childlike and innocent, reminds the reader of what “force” can and does take from us. Parents must explain terms and phrases such as “tanks,” “invasion,” and “nuclear weapons,” all while feeding and putting children to bed. The everyday tasks of the caretaker are perhaps another way of resisting what “force” does.

The Ukrainian word for “death,” “смерть,” (smert), is feminine. In a poem in which the speaker converses with Death, Halyna Kruk, translated by Sibelan Forrester, writes, “[ . . . ] my son, I can’t picture the war even to myself.” The mother herself doesn’t know war. It’s as if she asks the reader, “How could we have let this happen to our children, much less ourselves?”

In another of Kruk’s poems, translated by Sibelan Forrester and Mary Kalyna with Bodhan Pechenyak, this strategy of using metonymy for “force” introduces a bullet as a child. In this case, the bullet is like the one the soldier keeps on the battlefield “for his own temple.” The first line of the poem quotes a common Ukrainian expression, “The Lord saves those who save themselves.” Kruk introduces the metaphor of a pregnant mother, like “the living soil,” who believes that she will have to send her son to war. Already many children have been born in the war zone. Life demands to go on, even while it is being ended all too quickly at the very same time and place. And who can blame parents for thinking at this time that their children will be caught up in this war or another? In Kruk’s poem, the child is like the bullet that will save a life by ending it the way the mother, instead of the soldier, wants. That is, the child will work against what “force” can and does do to a person. But “force” can turn even a person who is giving life into a person incapable of caring about other life.

Does this poetry’s redirection of what “force” does, of death itself, create a form of resistance? Oksana Lutsyshyna, translated by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky, gives voice to a man “at the end of life” who says, “last night it hurt so bad/ that I forgot everything, even who I was.” There’s what “force” can do, make a thinking person into mere matter. But there is redemption in the man’s request when it appears again at the end of the poem: “don’t come to help me / help those who still want to // make children.” While he may have forgotten himself, he still gives meaning to life in general, still respects its continuation beyond himself.

Perhaps the idea at work here is to think of meaning that is beyond our everyday reality. Later, in “I Dream of Explosions,” Lutsyshyna also invokes the theme of the heightened sense of reality poetry can give a person: “you fall out of the world as out of a sieve / and you see: it’s not there, / it’s an illusion // so why does it still hurt / so bad.” Harsh reality would seem to be on the side of “force” and would remind us that we’re (in Weil’s words) “no more than matter.” Yet depicting human pain and suffering, even death, may work against the depletion and reduction of human beings into mere matter. So we need surrealism, we need poetry, not only to breathe and be animate, but to continue to assign meaning in order to resist succumbing to “force.”

But this task must be acknowledged as difficult, as impossible. Only a kind of blind or absurd, surreal faith in poetry can withstand what “force” does. One of the most cited poems in Words for War is Lyuba Yakimchuk’s “Decomposition,” translated by Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky. Yakimchuk writes, “there’s no poetry about war / just decomposition / only letters remain/ and they all make a single sound—rrr.” That “rrr” sound is the last sound many hear.

Nonetheless, there is still sound in these fragments of words and names that Yakimchuk describes. In the last stanza, she writes, “I have gotten so very old / no longer Lyuba / just a -ba.” In Ukrainian, “ba” could be an abbreviation of баба, baba, a woman, usually an older woman such as Lyuba says she has become. However, the interjection “ba” can also be a defiant response to what has just been said. The ending of “Decomposition” is quieter than a typical instance of the interjection “Ba!” But there is still sound, the last of the poem. Fragments of language can still have meaning. Perhaps, after fragmentation and decomposition and reduction, mere sound is a way of keeping meaning alive.