A decisive break came in 1987, when Ribeyro, who by that point had worked as a cultural attaché and been an ambassador to UNESCO, spoke with the Agence-France Presse about his support for a proposal to nationalize the banks in Peru. He also took the opportunity to say that Vargas Llosa’s vocal objections to such a plan meant he was a conservative opposed to “the overwhelming eruption of the popular classes who fight for their well-being.” Some retaliation came in 1993, in the autobiographical El pez en el agua (later translated as A Fish in the Water), when Vargas Llosa suggested that Ribeyro was always subject to an “instinct of diplomatic survival” and that he subsequently retracted his criticisms in private correspondence. The implication of these remarks was clear: unlike the steady rightward shift of Vargas Llosa, Ribeyro was content to go wherever the political winds would take him. Ribeyro, according to this reading, was therefore an apolitical figure quite unlike the author of The Time of the Hero and Conversation in the Cathedral, whose presidential run on a center-right ticket in 1990 had failed.

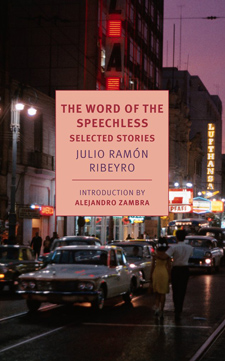

But Ribeyro’s short fiction, some of which has been translated by Katherine Silver and is now collected in The Word of the Speechless, tells a rather different story. As the title of this volume indicates, there is in fact a politics at play here even if it is one that consists of expanding perspectives rather than articulating clear positions. “In most of my stories those who are deprived of words in life find expression,” Riberyo explained in a 1973 letter to his editor. “I have restored to them the breath they’ve been denied, and I’ve allowed them to modulate their own longings, outbursts, and distress.” Although that effort to incorporate new voices is not always obvious throughout this career-spanning anthology (which also uses the letter excerpt as a sort of epigraph), there is unfailingly a space for studying the sentiments he identified.

One of the stories that effectively combines an emphasis on the under-represented with attention to affect is “At the Foot of the Cliff,” which dates from 1959. An impoverished father recalls how he and his two sons set out to create a home for themselves on a beach that sits below the city atop the rocks and that is supposedly a space where the state will not intervene. But this story about claiming land is also one about confronting loss. After one of his sons dies, the father utters a line that underscores his despondency and his disempowerment: “To lose a son who works is like losing a leg or like a bird losing a wing. I was like a cripple for many days. But life reclaimed me because there was a lot to do.” Everyday struggles leave little time for mourning, but things worsen when urban development later accelerates and guarantees the destruction of all their hard work. When the crew tasked with tearing everything down decides to give him one last night in his humble home, he remembers that it left him “humiliated though still master of my meager belongings.” Ribeyro powerfully captures this mixture of shame and a strange sense of diminished yet still definable power, which is to say a feeling of holding onto one thing in order to avoid acknowledging how another slowly slips away.

He strikes a similar tone in a devastating exploration of the ineluctable ties between indebtedness and embarrassment. Although the premise of “Meeting of Creditors” might suggest a plethora of pathos—Don Roberto, whose grocery store has gone bankrupt, must face the group of creditors who have assembled to determine a solution amenable to them but not necessarily to him—Ribeyro instead offers a stirring reflection on the relationship between distress and dignity. For Don Roberto, the latter is perhaps the only thing that the creditors cannot put a price on, but even as it ameliorates the effects of the former it still does not help pay off what he owes. Ribeyro captures these interior conflicts through understated yet penetrating descriptions, pointing to the way the shopkeeper “preferred to remain immutable and dignified, with the demeanor of a man who deserves an explanation rather than must give one.” The tragedy, of course, is that he does merit an explanation, but not for why a nearby competitor had succeeded where he could not. Instead, he wonders about the way language leaves indelible scars: “It was horrible, he thought, that words that had come into being to refer to objects could be applied to people. You can break a glass, you can break a chair, but you can’t break a human being, not like that, through an act of will. But those four gentlemen had delicately broken him.” Or to put it in other terms that Ribeyro would surely approve of: why does a concept like self-worth, which already has its pecuniary overtones, sometimes seem so inseparable from net worth?

*

That distinctive story of the creditors belongs to one of Ribeyro’s earlier collections, some of which also contain stories that recall those of precursors who were also contemporaries. There are, for instance, Borgesian-tinged trips and intrigue in “Doubled” and “The Insignia” as well as echoes elsewhere of Cortázar. While both competent and confident, these pieces are admittedly less captivating than those where Ribeyro commands a voice that is distinctly his, and one expects to encounter such vicissitudes in a survey of four decades’ worth of work. Thanks to this expansive scope, this volume provides a different view of Ribeyro than previous efforts to bring him into English, including translations of the short story collection Silvio in the Rose Garden and his first novel, Chronicle of San Gabriel. And while there has been one previous selection of his stories, titled Marginal Voices, that also culled from the same four-volume compilation known in Spanish as La palabra del mudo, this recent anthology from New York Review Books offers little overlap.

These new texts also crucially feature a new English voice for Ribeyro. If, as Alejandro Zambra argues in an introduction (translated by Megan McDowell), “Ribeyro’s sentences tend to brush up against the intensity of good poetry,” then we can certainly say that Katherine Silver captures that same force. She not only irons out the occasionally inelegant syntax in previous versions of Ribeyro’s sometimes sinuous prose but also consistently locates a rich sonority within it. Whereas a previous translator renders a description of the fruits of an orchard as being “a delight to the touch before becoming a gift for the mouth,” for instance, Silver instead furnishes the phrase “a delight to the touch before being a gift to the tongue.” Despite the identical beginning, the subtle shifts at the end ultimately allow for a lightness that makes the whole sentence resonate. In much the same way, she deftly incorporates explanatory phrases into a story with some untranslatable wordplay rather than relegating them to footnotes, thereby ensuring that readers remain ensconced in Ribeyro’s careful construction instead of slipping out into an extra-textual apparatus.

*

In the collection of fragmentary observations known as Prosas apátridas (Stateless Prose) since they belong to no recognizable genre, Ribeyro proposes there are two things we cannot really retain: pain and pleasure. “We can, at most, have the memory of those sensations,” he writes, “but not the sensations of those memories. If it were possible to relive the pleasure that a woman gave us or the pain that a sickness caused us, our life would become impossible. In the first case it would begin to be repetitive, in the second tortuous. Because we are imperfect, our memory is imperfect and all that returns to us is that which cannot destroy us.” One of the most moving pieces from The Word of the Speechless is a searing self-portrait of something that delivered such suffering and satisfaction to Ribeyro in seemingly equal doses: the cigarette.

Perhaps the most unexpected attribute of “For Smokers Only” is that it makes cigarette consumption both appealing and appalling, simultaneously resplendent and repulsive. As Ribeyro acknowledges, writing and smoking intertwine like the tendrils emerging from a cancerous cylinder’s flickering end—and not only because the hand tapping off the ash can be the same one tapping typewriter keys. Smoking also introduced him to characters who, as the piece readily reveals, bring out the best of his prose. In Spain, for instance, he meets a veteran of the civil war who sells individual cigarettes out of a basket and who is surprised that it takes Ribeyro so long to ask if he might buy a handful on credit. And in Paris he befriends Panchito, a fellow Peruvian who gives him his first Pall Mall and who, as Ribeyro later discovers, was wanted by Interpol.

Yet despite the allure of the cigarette and the connections it allows him to develop, Ribeyro recognizes that he must also account for the toll it inevitably takes. There are hospitalizations that begin to be more serious and more frequent. (At one point, he remembers, “it could be said that the ambulance had become my most common form of transportation.”) And then there are the ingenious yet devious strategies to leave the hospital to light up once again, including one that involves smuggling silverware into socks to feign weight gain. But a certain despair also surfaces as he struggles to recall what exactly explains this fixation with smoking. An opacity lies behind the obsession that makes it into a misunderstood obligation. As a result, Ribeyro, like so many of his characters, confronts a set of circumstances that he only accepts but never truly changes.

Ribeyro once described those consistent thematic concerns of his stories as the process of creating a “climate of frustration, failure, and despondency.” What had varied across his considerable output, he said, were “the technique and the place; a good number of them take place in France and Italy.” This collection contains some of these continent-crossing transpositions. “Nuit caprense cirius illuminata,” for example, narrates the fleeting possibility of rediscovering a lost love, and even though it dates from 1993 it ends with a moment of doubt not unlike those in some of his earliest stories. Similarly, disappointing encounters with literary idols appear in both “Ridder and the Paperweight,” which is set in Belgium, and “A Literary Tea Party,” which portrays the frustrated expectations of a group eagerly anticipating a visit from a Peruvian writer who has briefly returned from Paris. These variations on a form demonstrate how Ribeyro masters it by considering all possible permutations, and we even glimpse parts of this process in “The Solution,” where an author walks his friends through an array of options for finishing a story about infidelity and carefully charts the effects of each choice. But the same could not be said of Ribeyro and his health: he died of cancer in 1994, at the age of sixty-five.

*

In his last year alive, Ribeyro decided to permanently return to Peru, where he acquired a habit that occasionally left others speechless. In the karaoke bars of Lima, he would request old boleros whose lyrics no one else knew and enjoy belting out verses like “I am a prisoner of the sea’s rhythm, of an infinite desire to love, and of your heart” in a deep and raspy voice. One of his characters could have easily sung such a line, and two stories in this collection show how Ribeyro put other wordless forms music to use on the page.

In “Silvio in El Rosedal,” a forty-year-old man inherits a country estate that his father had acquired just three months before dying. Although he considers selling it in order to live off the profits, Silvio eventually settles into a rural life thanks to inertia more than any clear intention to do so. It is therefore a story of searching for meaning and trying too hard to locate it in unexpected places, including in a pattern in the estate’s rose garden. One day, as a distraction, he picks up his childhood violin and, taking advantage of his life of leisure, devotes himself to polishing his skills. Along with a traveling musician, he even plays Bach’s Concerto for Two Violins at a performance for local landowners whose failure to appreciate it leads him to return the instrument to its case. This disappointment is later doubled when, at the story’s end, he pulls out the violin once more and plays better than ever before. The only problem is that he alone constitutes the audience for this performance, making it another of Ribeyro’s arrangements of contrapuntal frustration and isolation.

Closing out the collection is “Music, Maestro Berenson, and Yours Truly,” which recounts a young man’s rediscovery of classical music thanks to a friend and to the arrival in Lima of an Austrian exile who revitalizes the National Symphony. But as the two fans meet the maestro on different occasions over the years their admiration is diminished and a sense of disillusionment emerges. The decline of the once-great conductor then reaches a nadir by the final section, when, many years later, the narrator reencounters his early idol in Cuzco at the home of an army officer. There, however, his baton leads no musicians but only accompanies a cassette recording of Beethoven’s Fifth, and the narrator is dismayed to discover this star of his youth now reduced to mere spectacle.

As he relentlessly brings such letdowns and setbacks into view, Ribeyro changes how we perceive the world by alerting us to the obstacles it presents. This, too, is a form of practicing politics, or at the very least contributing to conversations about it. But it is also, according to one section of the Prosas apátridas, the sign of a true artist. Ribeyro suggests that this figure “does not change reality; what he changes is our gaze. Reality continues to be the same, but we view it through his work, which is to say through a different lens. This lens allows us to access degrees of complexity, meaning, subtlety or splendor that were already there in reality but that we had not seen.” Although the author of The Word of the Speechless was not writing about himself, he might as well have been.