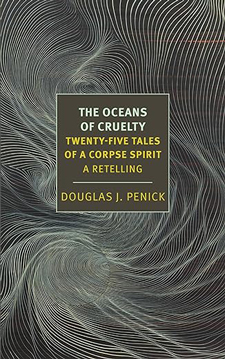

Referred to as “one of the oldest collections of stories in the world,” the Vetāla tales are a narrative puzzle for both the protagonist and reader which questions the spiritual and corporeal nature of being and humanity. The four preambles to the twenty-five main stories describe the Vetāla, or corpse-spirit who was once a man. Having voyeuristically dreamt of the deities Śiva and Pārvāti in the midst of the carnal and literary delights responsible for creating the world, Brahman, the son of an oil merchant, describes the dream to his wife as they indulge his own irrepressible and inevitable needs on waking:

He gazed in awe at their vast coupling. He could not help hearing Śiva’s low rumbling as he delighted Pārvāti, whispering one story, then another, twenty-five in an unbroken stream. In the morning, when he woke, Brahman could not help himself. He made love to his wife and told her these stories as he had heard them.

The anger incurred at a mortal both intruding upon and ruining such divine intimacy with coarse mortal language results in his being turned into a living corpse—the stories so carelessly repeated in passion now interred within his dead flesh.

The corpse-spirit is granted a way to be released from his punishment. He must tell a King the stolen stories he holds. In turn, the King must “respond to each story as if it were real, only if finally, words fail him, only then will you be freed.” This opening, fantastic in both senses of the word, presents the reader with a no less contemporary issue: the ability of perspective and retelling to shape and bend a narrative. In F for Fake, the 1975 Orson Welles docudrama in part about art forger Elmyr de Hory, Welles explores the shifting nature of truth and falsehood by blurring the divide between the two. Sections delve into his own experience of The War of the Worlds (CBS, 1938) broadcast, taken at first as a real event, and the presence of Clifford Irving, de Hory’s biographer, who had also written a (fake) autobiography of Howard Hughes. This idea is echoed in Oceans as the King is forced to consider every point of view presented in the story-riddles, rather than remain in the comfort of a singular narrative.

In the fourth introductory story, “A Tide of Tales: King Vikramāditya,” a golden apple of immortality is passed from lover to lover in a way that recalls the fated diamond earrings of Louise de Vilmorin’s Madame de, where the narrative unfolds through the eyes of the jewels’ subsequent owners. With the apple, what starts as a gesture of spousal love and sacrifice becomes a chain of transactions representing increasing lust and the desire for royal favor. As with the diamond earrings, King Bathari’s gift to his beloved wife makes its way back to him, here via the hands of a scheming courtesan. This results in the dissolution of the kingdom and his brother King Vikramāditya coming back to claim it from a demon.

The unrestrained curiosity, appearing in everything from Greek mythology to Japanese folk tales, is also present here. Vikramāditya’s inability to heed a warning not to speak to the Vetāla results in his being trapped in Síva’s puzzle-like reprieve: an infinite task seeking what appears to be an impossible solution. This is a trope that continues throughout, with each story’s characters facing whose outcomes are so vastly different that they question the ideas of free will and determinism, a conundrum recognised by the stories themselves. “There was no end to all this going and going, and no meaning,” writes Penick in the story “Vows,” “just a cascade of fragments, all incomplete.”

A retelling constructed from multiple existing translations rather than an entirely new translation offers something unique. What Penick (who is also a translator) is doing is twofold: it requires a sensitivity in handling such multiplicity while bearing in mind that any rearranging of details must remain as coherent and lyrical as the works referenced. Lyricism must be stressed as what is being done here is more akin to verbal storytelling; this can and should be considered a vital arm of translation. It functions as a reminder that, after their popularization, any subsequent retelling or editing of works such as Grimm’s fairy tales does as much in terms of remembrance and erasure as direct translation from an original language.

What has passed into popular consciousness in various depictions are stories such as Grimm’s “Cinderella” but without the bloodied glass slippers due to the stepsisters’ slicing off parts of their feet to fit; other stories, such as “The Salad” (also known as “The Donkey Cabbage”)—in which two deceitful women are changed into donkeys and then regularly beaten and starved, one until death—have not. Cruelty is an afterthought in modernizations of “Cinderella”; in the original, it was a constant that showed both its characters and happy ending in sharp relief. It is difficult to imagine a “clean” version of “The Salad,” whose plot necessarily hinges on deceit, violence, and implied sexual submission. In the context of a trend towards sanitization of fairytales, it is thus not surprising that this tale is less well known. However, it was included in a 2012 Penguin edition of Philip Pullman’s retelling of his fifty favorite tales, of which he writes in the introduction, “my main interest has always been in how the tales worked as stories. All I set out to do in the book was tell the best and most interesting of them, clearing out of the way anything that would prevent them from running freely.”

In light of changing societal norms and audience requirements, tales are inevitably changed, and there are valid arguments for doing so. But removing all references to cruelty or deceit also has its downsides. Human nature is frequently ugly, but its presence in fiction offers a distance from ourselves not available elsewhere. The goddess Kali says in “Service,” “life continues by violence and death,” a sentiment echoed later in Penick’s version of “Wise Birds,” “I wish I knew stories of a better, happier world”; the story-cycle, as key to understanding this, is both essential to the narratives of Oceans as well as the reader. The best fictional self-awareness successfully performs an existential sleight of hand: we see ourselves more accurately when presented with alternate selves.

To edit or erase can come across as self-denial despite good intent. Stories can give a sense of moral or societal positioning and the boundaries of conduct; they show when it is acceptable to disregard or manipulate them. Because of their advisory nature, it becomes necessary to reveal everything from lust to venality, violence and deception. Law alone does not give a person the sole sense of who they are in the context of their fellow humans; stories such as the ones in Oceans do by allowing a space to consider our behavior—from desire to violence—and, even if seemingly insignificant, how it forms part of the greater web of our existence. Ultimately, for a story to succeed, a character’s behavior must justify the story’s narrative rather than our biases—this is a seemingly obvious aesthetic statement which is anything but in an era of personal moral justification of art. The lessons at times may be horrifying, but they are necessary as the connection between fantasy and reality.

The long-term cultural coherence of a retelling is dependent in part on the desire of the writer to maintain a legacy true to origin while applying changes. Ideally, there must be a love for the material but also a more pragmatic eye on the story as existing out of time and beyond the reteller, as Pullman intimates. It is immediately apparent in Penick’s foreword there is a near reverence for the fantastic stories from his childhood. Not only does he cite Grimm’s tales and Greek myths, but he also recalls his mother reading the Old and New Testaments to him and his siblings. In an anecdote about his love of Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid,” he admits he has never actually read it. This is another realization suggesting that the passing on of stories is about the intensity of feeling regardless of the medium in which the story itself is encountered.

Penick deftly handles The Oceans of Cruelty with a translator’s eye and a writer’s hand. In doing, so he succeeds in conveying the multiplicities of tone: an earthy, at times brutal matter-of-factness, an elegant sensuality which understands the entwining of violence and the body, and touches of humour. These experiences are entirely human but not limited to us: in “Wise Birds,” an erudite exchange between two caged birds about sex displays much female wisdom:

“Kind Parrot, I regret to say that I have absolutely no desire to have sexual intercourse with any male.” “But why?” The parrot asked. The mynah answered: “Dear Gem-Like Friend, I am sorry, but I have observed that in every species, those of the male sex are always the most deceitful and predatory, the most violent, the most likely to kill their mate. Surely you have noticed this?” The parrot was deeply offended and shook its head.

The body is the carnal heart of the tales. A man is punished for being privy to the pleasure of the gods as well as taking his own; as a direct result, a King must decipher the stories of humanity within the corpse-spirit’s skin in order to free himself and, in turn, it. That the King is unable to stop himself from answering the questions of the Vetāla at the end of each story says much about our continued response to stories and the increasing inability to separate the nuances of reality and fiction in creative work.

Aesthetically, the solution to this problem is not to uphold a rigid boundary between reality and fiction. It can be argued it is necessary to consider the unreality of narrative as real in order to better grapple with its underlying questions. One must immerse oneself in order to realize the depths of the water. The difficulty presents itself when the reader fails to extricate themselves from the fantasy, instead preferring to remain in the false reality of the created narrative as a method for avoiding that which should be confronted. The King, despite his repeated error of answering the corpse-spirit, understands he must find a way beyond it, even as he is held rapt by its stories.

Regarding Ryan Murphy’s recent retelling of the story of Truman Capote and his society Swans in Feud (FX, 2017)—based largely on Capote’s Women by Laurence Leamer with episodes written by Jon Robin Baitz), an NBC article states, “although Feud is grounded in true events, Baitz admitted that the creative team exercised some creative license to tell this “speculative” iteration of Capote’s story.” Baitz adds, “there’s something impressionistic about playing with the life of an artist and his milieu that doesn’t necessarily depend on chronology or fact, that leaves room for impressionism and hallucination in order to explore the inner life of the characters.” Impressionism and hallucination are apt words which get to the heart of both the attraction and the potential issues of interpreting retellings. They suggest the contradiction of distance and immediacy which the viewer or reader is subject to.

Like Capote’s Swans, women here, both mortal and divine, are narratively prominent and active in almost every story. In “True Love,” a princess’s sexual appetite and jealousy becomes the basis for a greater question of how and whether we should fulfil their demands. Surprisingly, for ancient stories, it includes an open reference to menstruation that is understood without judgement by a male character, in contrast to Capote’s infamous sex and menstruation scene in “La Côte Basque, 1965” (Esquire, 1975)—the gauze-thin veiling of the private lives of the Swans that resulted in his ostracization. In “Three Suitors,” the death and later reanimation of a wooed woman allows Penick to bring into focus the cruelty and ineffectiveness of emotional extremity and the body weaponised and/or destroyed.

The body in Oceans is subject to the puzzles and possibilities of everything from magic to biology. The fate of characters is determined by how these are interpreted but to do so opens up yet more complexity. The real curse—or gift—of the corpse-spirit is that within a finite number of stories it reveals the infinite issues of human nature.

This is not unique to the Vetālas: the love, lust, and duty that spring from the body continue to be main themes in the arts because they have no straightforward resolution and are therefore ripe to be narratively manipulated. If we say of Feud that, despite creative liberties taken with the factual narrative, it remains broadly realistic, then it is reductive to say that Oceans is merely a collection of fairy tales; the behavior outside of their fantastic wrappings remains true. the nature of good stories is that they deliberately play with manipulation within and without. It is up to us to recognize that we are an integral part of it.

In the notes at the end of the book, Penick remarks specifically on some of the changes made based on two of the main source translations used. His choice to order the stories in this version comes from The Baitǎl Pachchisi; Or The Twenty-Five Tales of a Sprite by John Platts (Alpha Editions, 2021), translated from the Hindi text of Dr. Duncan Forbes. Names, as they appear in Oceans, are from Chandra Rajan’s Sanskrit translation of Śivadāsa’s The Five and Twenty Tales of the Genie (Penguin Classics, 2006). Full credit is given to the extensive list of other works used in his research.

Part of what makes translation a success for the reader is its rhythm. There is an instinct at work in most readers of translated writing that recognizes this, the cadence and lyricism of what was transformed into what is, despite never truly knowing the former. What is being done here is in its way just as difficult: the combining of multiple voices. Penick is not unlike a conductor bringing together the various instruments of the orchestra. The prose of his retelling flows from one story to the next, capturing the essence of what makes retold stories endure: a love out of time which exists for readers past, present, and future.