Finding the language to communicate trauma and its aftereffects—the task “to put disaster into words”—emerges as one of the book’s central concerns. In therapy, in conversations with other survivors, and ultimately in a courtroom, where Bon is brought into an encounter with her attacker decades on, readers witness women striving to put words to unspeakable experiences. “It’s important to me that what happened to me is given a name,” Bon notes, while at the same time highlighting language’s inability to communicate the full horror of her traumatic experience: “There are no words, when you’re nine, to talk about something like this.” By problematising the power and limits of language, Bon’s memoir creates another layer of responsibility for the translator of the book: each word in English must be selected with the same precision and scepticism that Bon devotes to its French equivalent. Diver notes that in translating the text, her main aim was to evoke the “same immediacy, depth and emotional response” as the original—and all of this hinges on the ability to arrive at the mot juste in a memoir concerned with the immense difficulties thereof.

The violence with which language is used and abused in Bon’s life contributes to many of the darkest manifestations of “immediacy” found in the book. Passages full of profanities occur frequently—typically delivered by men at women—and Diver handles such moments with great skill, retaining the force of the original through considered, contemporary vernacular choices in English. During the trial, for instance, Bon and other witnesses are subjected to the vitriol of their assailant in diatribes directing blame at others for his crimes: “That child, you’re the one who raped her, arsehole! You’re the child rapist, you scum!” In another example, during Bon’s train commute, a drunken group of rugby fans sing obscene songs extolling rape and violence against women: “The ramparts of cunt / it hardens, and discharges, / And shoots cum up your cunt.” The memoir highlights the shocking, wounding effects of violent language, and its lasting damage is shown most acutely through Bon’s inner monologues. Intrusive thoughts, destructive impulses, and distressing flashbacks to the events of her youth recur throughout, and Diver’s English version effectively retains many of the sounds, rhythms, and imagery that create the distressing “immediacy” of Bon’s internal world:

between her thighs

a big rough hand bashing her vulva bashing

fingers forcing and going inside

the pain of a fingernail on the vagina walls

He is inside me he put his fingers inside it’s him

Terror, hate, violence, contempt, disgust,

pain, power, perversion.

All mixed up. All confused

But while words are shown to inflict great harm, they also equip Bon with the ability to reframe the experiences in her past, and better navigate their lasting effects in the present. Significant breakthroughs in Bon’s life are demarcated by her discovery of precise medical and legal terms to apply to her experiences. Her disordered eating, she learns, can be referred to as “bulimic hyperphagia,” and she remarks: “I wish she had said those words to me back then.” And when she first uses the term “rape” to refer to her experience, she reflects: “What if the key she has been searching for all these years, all these years of seeking in vain, what if the key was that word?” Bon levels sharp criticism at societal and institutional ignorance around sexual assault: “How is it, in our over-informed society, that this information is not freely circulating?” The lengthy exchanges between Bon and psychiatrists, detailed expositions on current legislation, and accounts of traumatic amnesia and PTSD worked into the memoir all appear an attempt to tackle such ignorance head on. Diver works with unerring precision across the book’s many lexical fields, carefully rendering the medical, psychiatric, and legal terms found in Bon’s French. For this, Diver draws on the expertise of criminal barristers and other experts to verify technicalities, and acknowledges the importance of “collaborative” translation in the process. Her resulting English version is accurate and informative, as Bon evidently intended.

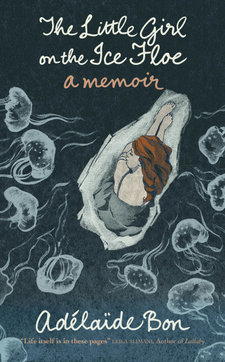

With striking creativity and flair, Bon also works around the quest to articulate the unfamiliar experiences of PTSD by devising an allusive, lyrical language all of her own. She achieves this through a series of recurrent motifs in the book, particularly the image of “jellyfish,” deployed throughout to encapsulate the distressing flurry of traumatic memories, repressions, and impulses she experiences, years after the attack she suffered. “The jellyfish spread their umbrellas wide and let their silky filaments dance in the icy waters,” she notes when speaking of her inability to recall and relate her trauma. However, there’s an unfortunate, if inevitable, loss in Diver’s translation here. In translating the French word “méduse” into the English “jellyfish,” Diver’s version diminishes the potency evoked through a central allusion in Bon’s original—that of the Medusa of classical mythology, who was raped by Zeus in the temple of Athena. An important, climactic passage in the book therefore loses much of its impact, when Bon declares: “I am Medusa, granddaughter of the Earth and Sea [ . . . ] I am what is left of a woman after she has been raped. And writing reassembles me, reconnects me, restores me.” Nonetheless, for the most part, Diver replicates Bon’s elegant, elliptical phrasing seamlessly, and works in some neat flourishes of her own that afford Bon’s French original new life and resonances in English—“le cours du rêve” becomes “the unfolding of a dream”; elsewhere, during an encounter between women in a psychiatrist’s waiting room, Diver translates: “the words ‘me too’ float with tenderness in some of the eyes.”

The past few years have seen several cases of childhood sexual assault make international news, while women across the world have found catharsis and collective solidarity in saying “Me Too.” It’s perhaps surprising to note that research in the field of trauma is only a relatively recent phenomenon: the term PTSD only came into use in the 1970s, while the academic field of literary trauma studies emerged in the decades that followed, as theorists such as Cathy Caruth and Shoshana Felman advanced ideas around the links between trauma and creativity. The proliferation of sophisticated writing in more recent years on the subject of childhood sexual abuse, from Roxane Gay’s Hunger, to Emma Glass’s Peach—and now Adélaïde Bon’s work, lend credence to such theories, as writers find new ways to stretch language and literary genres in a quest to give voice to their most harrowing experiences. When asked for her view on the necessary components to produce a good translation, Diver states: “first, you need a good book—and this is a great book.” In her resourceful, creative translation, Diver has found a means of giving Bon’s accomplished memoir a new life, and a new audience in English, navigating its ethical, technical, and creative complexities with skill and care.