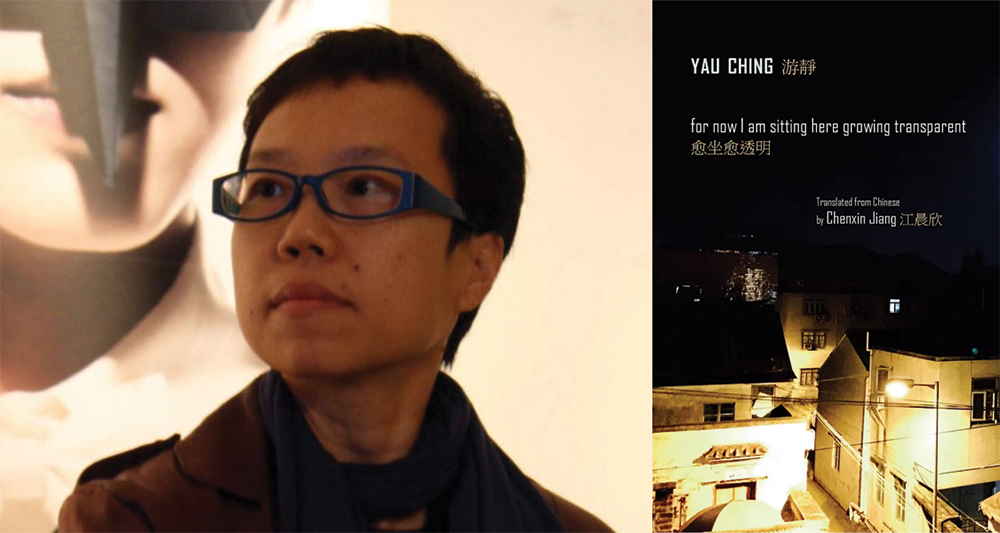

for now I am sitting here growing transparent by Yau Ching, translated from the Chinese by Chenxin Jiang, Zephyr Press, 2025

In the poems of Yau Ching’s For now I am sitting here growing transparent, there is a longing, on the part of the poet, to engage with literature for its own sake. She declares that: “I’ve always liked the idea of reading in bed, a life spent / falling asleep reading waking up / and reading more . . . / I only ever write on assignment / my life is ten cents per word no pay no words.” Exemplifying how Yau uses softness and vulnerability in the stead of impassioned critique, readers are likely to find themselves entranced by these poems, their fiercely gentle existence outside of social hierarchy. The resulting text is both relatable and transformative.

Translated from Chinese and published by Zephyr Press, For now I am sitting here growing transparent is Yau’s fifteenth book, and her first to be translated into English. Gathering work from Yau’s other collections, this text is a kind of mid-career retrospective, making Yau’s work accessible to English-speaking audiences while also curating the most resonant and crafted poems from her corpus. These poems have been gathered and treated with great care by translator Chenxin Jiang, whose introduction foregrounds the reader in both the social and political context of Yau’s subtle poems, as well as their linguistic deftness and adventurousness, showcasing the enduring relationship between these two creatives. Admitting that Yau’s poetry provides a challenge due to its “wordplay and playfulness with form,” Jiang nevertheless comes up with solutions that match the idiosyncrasy of the originals. READ MORE…