Guatemalan scholar Rita M. Palacios’ body of work reexamines the hegemonies that mediate literary, cultural, and knowledge production, particularly in Maya oral storytelling, literature, and material culture. In the book she co-authored with Asymptote’s former editor-at-large for Mexico, Paul M. Worley, Unwriting Maya Literature: Ts’íib as Recorded Knowledge (University of Arizona Press, 2019), they argued for a decentering from the Euro-American critical vocabulary of literary theory and arts criticism through the lens of ts’íib—”an understanding of Maya artistic and cultural production that includes and exceeds the written word.” Drawing from Maya artists and authors such as Calixta Gabriel Xiquín, Waldemar Noh Tzec, and Humberto Ak’abal, whose œuvre range from murals to textiles, from cha’anil (‘performatic’) to ceramics, from monuments to poetry, Palacios and Worley make the case for the ts’íib as one of the various Indigenous-centric departures from and unlearnings of our colonial worldviews on literary production and knowledge systems.

In this interview, I conversed with Dr. Palacios on ts’íib as a form of autohistorical knowledge production that is beyond the Western imaginary, the Maya and non-Ladino writers and writings within Guatemalan and Central American literatures, and the rightful refusals against translation.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): In a conversation on Mexican and Guatemalan literatures with Paul M. Worley, you said

[T]he many challenges (structural racism, censorship, a lack of government funding, to name a few) that writers in countries in the Majority World face directly impact how and what is written, how it’s published, and who it reaches, and so we, readers and critics, would do well to pay attention.

Can you speak more about these gaps and dissimilarities in terms of knowledge production, especially in literature, in the Global Majority versus the North Atlantic?

Rita M. Palacios (RMP): Given the way Western political and economic powers have shaped our world, the anglophone North Atlantic enjoys a certain monopoly over the manner in which we think and write about each other, privileging certain modes of artistic production over others, as well as creators, reading publics, and even the critics. This is not to say that we are helpless or that we are wholly bound by a system that privileges and rewards those who uphold it. It does mean that things are much more challenging for those who live, think, and create outside those parameters.

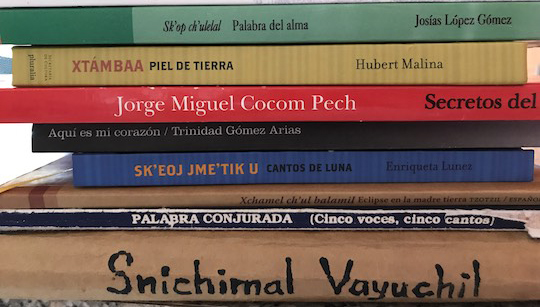

Generally, when it comes to literature, that which is written, packaged, and sold by the millions is not a literature that aims to represent us all, but a literature that affirms the places (real and imagined) we already occupy and the systems built around them so that we continue to inhabit these spaces, sustaining those big great powers. Despite the challenges their authors face, the literatures of the Global Majority are rich, diverse, and challenging; they are multilingual, multivocal, and multiversal. Rarely are these literatures sold in the same manner as blockbuster novels because of the threat they pose. And these authors recognize the danger of being subsumed into “national” or canonical literatures, as is the case with Mikel Ruíz (Tsotsil) who notes the tokenization of Indigenous literatures in Mexico (2019). READ MORE…