It’s been a fantastic year for literature and, consequently, not such a stellar year for my bank balance as all these purchases have begun taking over my apartment. I recently discovered that there is a word for this condition in Japanese, “tsundoku”; letting books pile up unread as you buy new ones to add to the literary Tower of Babel rising ever higher in your apartment. But sometimes there are books that you leave the store reading and can’t put down, and there have been quite a few of those this year.

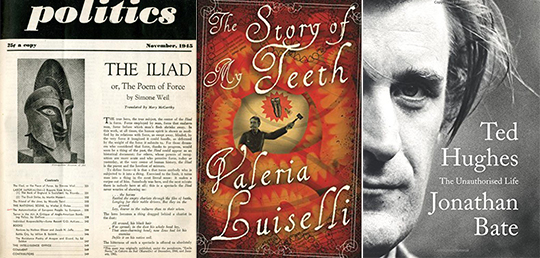

Jonathan Bate’s Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life was one such book, a lucid and meticulously researched biography of the late poet, who also acted as a champion of translation and literary internationalism through Modern Poetry in Translation (MPT), the magazine he co-founded in 1965 with Daniel Weissbort, through the founding of Poetry International in 1967, and through his own efforts at translation. Most notable of these efforts were his translations of Hungarian poets during the 1960s and 1970s, living in ‘the Other Europe’ of the Cold War era.

In what might well be a q-memory, I recall coming across Ted Hughes’ poem ‘The Thought Fox’ at an early age within an anthology of British poetry owned by my great-granddad. Though I wasn’t to know it at the time, The Hawk in the Rain would later become a touchstone during my teenage years in rural North Yorkshire. Coming from a similarly unremarkable background, Hughes was someone who didn’t forget his countryside roots, but was in fact sustained by them; in short, he was one of us. Though there has been a huge amount of press around the book for its more scurrilous content, an unavoidable consequence of the ever-profitable ‘Plath industry’, Bate successfully puts Hughes over as someone who lived and breathed for his art; contained it within the marrow of his bones, and pursued an unwavering, unforgiving dedication to his art that brought terrible costs to his life off the page.

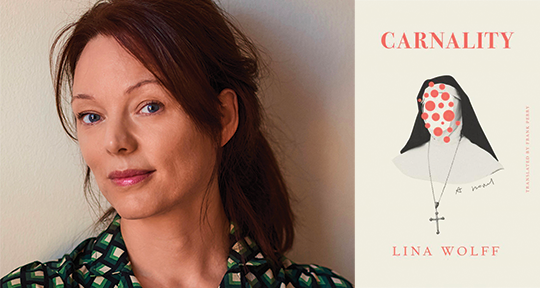

After featuring in our summer issue, I quickly snatched up a copy of Valeria Luiselli’s The Story of My Teeth when Christine MacSweeney’s wonderful translation hit the shelves of my local bookstore in September. Shortly after beginning the novel, it becomes obvious that Luiselli is sitting comfortably on the edge of greatness; uproariously funny and scathing in its critique of the absurdities and banalities of modern life, the book was just a delight to read from beginning to end. For lovers of the adroit wordplay of Joyce and the ironic farces of Ionesco, this book will make a perfect stocking filler.

Another translated work that has stuck with me throughout the year, particularly in light of the refugee crisis in Syria and the ongoing debates around military action against the self-styled Islamic State, has been Mary McCarthy’s translation of Simone Weil’s seminal essay, ‘The Iliad, or the Poem of Force’. A meditation on the nature of war and violence, it shows, on the one hand, why the classics are still relevant to our understanding and navigation of the issues thrown at us in the modern world. On the other, it reaffirms warfare and violence as a dehumanising force that strips both victim and aggressor of all humanity. Written on the eve of war in 1939, it remains one of the most moving literary essays ever written.

David Maclean is a freelance journalist and writer based in Manchester, United Kingdom. He is a Marketing Manager for Asymptote and Editor of Angle Grinder Magazine. Their inaugural issue, “North,” will be released in January 2016.