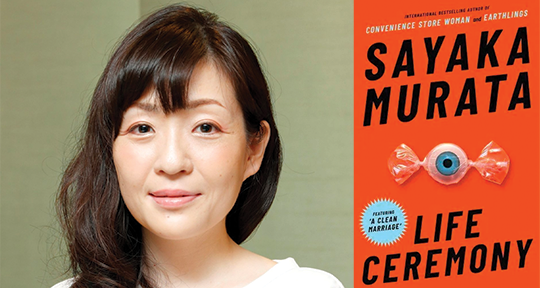

Life Ceremony by Sayaka Murata, translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori, Grove Atlantic/Granta, 2022

From Sayaka Murata, the award-winning author of Convenience Store Woman and Earthlings, comes Life Ceremony, a debut compilation of her short stories. The collection is unsettling, paved with the disturbances of odd people and new customs nestled amidst familiar words and routines;. Instead of burials, human bodies are recycled—a beloved father-in-law’s skin might be used as a bride’s veil, a person’s hair for a cardigan, human bones for chair legs. Instead of funerals, there are life ceremonies, where mourners dress in “skimpy clothing” to partake in eating the body of the deceased before going off in pairs for “insemination.” One woman is convinced that she has been reborn into an ordinary family in contemporary Japan, when in her previous (real) life, she was a warrior with supernatural powers from the magical city of Dundilas. Another woman falls in love with her curtain and feels betrayed when she walks in to find her boyfriend (who somehow has confused it for her) wrapped in its folds on her bed.

Sayaka Murata is a master of delivery, and in Ginny Takemori’s translation, it becomes clear that the way to convey these odd stories in all their philosophical force is to do it deadpan, matter-of-factly, and sometimes, coldly. But—there are breaks, moments that aren’t so much characterized by their coldness but by their sincerity, their characters’ confusion, and their loss. When Naoki, who is ethically opposed to using furniture or clothes made of human corpses, faces his late father’s dying wish to have his skin used in his son’s wedding, he is thrown off balance and says vacantly: “I can’t. . . I don’t. . . I really don’t know what to think anymore. Until this morning, I was confident about how to use words like barbaric and moved, but now it all feels so groundless.” We are made to sympathize with him even amidst bombardments of oppositional, universal ideas, derived from a new ethics that says discarding any part of a human is wasteful—one that asks: how is using human hair any different from using another animal’s?

In “Life Ceremony,” Maho can’t bring herself to partake in the ceremonial eating of the dead following an instance, thirty years ago, when she was bullied for suggesting the very thing that everyone does so casually now. She says to her friend Yamamoto, who also doesn’t eat human meat: “It’s just that thirty years ago, a completely different sense of values was the norm, and I just can’t keep up with the changes. I kind of feel betrayed by the world.” I too felt betrayed by the world in Murata’s novel, suddenly becoming painfully aware of how fast change comes via contemporary mediums—how many of our habits and values are dictated by global capital, and how much effort it takes to resist, even if only for the reprieve of a few moments to think and form opinions. How lonely it is both to belong to a world like this, and to be an outlier. READ MORE…