In the first month of 2025, the offerings of world literature are as rich as ever. To help you on your year of reading, here are ten titles we’re most excited about—a new translation of a stargazing Greek classic; the latest from China’s most lauded avant-gardist; a rediscovered Chilean novel of queer love and revolution; a soaring, urgent compilation of Palestinian voices; surrealism and absurdism from an Italian short story master—and many more.

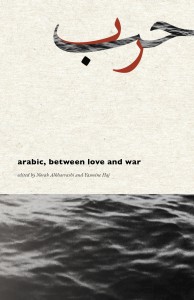

Arabic, Between Love and War, edited by Norah Alkharashi and Yasmine Haj, Trace Press, 2025

Review by Alex Tan

Addressing itself to the subtle but immense interstice between the Arabic words for ‘love’ and ‘war’, which differ by only one letter, Trace Press’s community-centric poetry anthology is as much a testament to beauty and survival under the conditions of catastrophe as it is a refusal to perform or fetishize suffering for a white gaze. The bilingual collection is, further, an intergenerational gathering of voices: canonical luminaries like Fadwa Tuqan are assembled alongside contemporary lodestars like George Abraham.

Throughout the volume, language gives in to its fecundity, at times carried by a voice that “condenses history to the depths of silence”, at others seeded within a word that “alone was enough to wither a tree”. The whispered syllable, across utterance and inscription, temporarily suspends the cruelties of the real: “I love calling you habibi / because then I feel as though they haven’t destroyed our cities.” In shared intimacy, an interregnum emerges, fragile as the stroke of an ر.

But how far can one measure the ruin and the specter of love in sentences? “I write rose and mean nothing,” the poet Qasim Saudi ventures, as if refuting the possibility of romanticism. The surveying ego can also be a trap—“my I wounding me”. Many of the writers here disclose a longing for dissolution, for blunting the edges of the self so that a liquid, collective consciousness might emerge in its stead. In Lena Khalaf Tuffaha’s idiom, “you never saw it coming, this cleansing, / how we have become this ocean”. Nour Balousha’s plangent question echoes, “Who told the wind that we were leaves?” READ MORE…