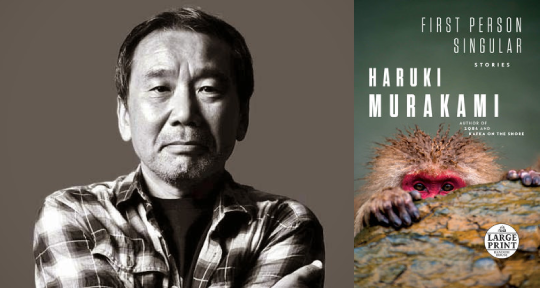

First Person Singular by Haruki Murakami, translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel, Knopf, 2021

In Haruki Murakami’s short story, “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning” (from his 1993 collection The Elephant Vanishes), the archetypal Murakami protagonist—an unreliable, doubtful man—fleetingly encounters an unfamiliar girl on the street and suddenly realizes she is the 100% perfect girl for him, though he has never spoken to her, nor finds her particularly beautiful. Instead, this melancholic, gently absurdist piece concerns itself with what the narrator would have said had he approached the girl. After dismissing a number of ridiculous ideas, the narrator decides on a long fabulist story, in which a young girl and young boy meet, discover they are one hundred percent perfect for each other, and separate to test their feelings. While apart, however, both lose their memories, and when they eventually encounter each other again, both only briefly acknowledge that they are perfect counterparts, but still go on to forever disappear from one another’s lives.

The story, which later served as inspiration for Murakami’s novel 1Q84, employs the author’s recurring narrative device of intermingling reality and unreality in the minds of his narrators, largely applied to the fleeting but transformative romantic encounters between men and women—most famously evident in his early bestselling novel, Norwegian Wood. It also reflects Murakami’s longstanding thematic concerns of loss, estrangement, doomed love, and loneliness. Notably, the young girl and boy not only become estranged from each other, but also from themselves in the loss of their memories; this theme of disconnection unites the stories in the author’s latest release, First Person Singular, fluidly translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel. The collection is his first since the English publication of Men Without Women in 2017, and returns to Murakami’s perennial fixations with jazz music, baseball, and mysterious meetings with women and animals. They are all narrated by an aged writer—resembling Murakami himself—who wistfully reflects on loosely chronological formative experiences. In this way, the stories blur not only dream and reality but also author and narrator, playfully employing the lens of memory to grapple with how we transcend—or fail to transcend— the disconnections that occur between others and ourselves.