In this week’s selection of translated literature, we present Hassouna Mosbahi’s expansive, dreaming portrait of Tunisia through the recollections of one man’s life, as well as Nataliya Meshchaninova’s precise, cinematic cult classic of a young girl carving her own way through abuse and neglect in post-Soviet Russia. Read on for our editors’ takes on these extraordinary titles.

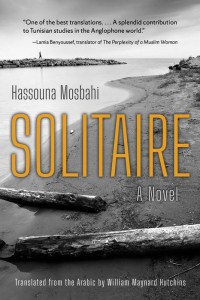

Solitaire by Hassouna Mosbahi, translated from the Arabic by William Maynard Hutchins, Syracuse University Press, 2022

Review by Alex Tan, Assistant Editor

The essential core. The innermost heart. The pupil of the eye. The central pearl of the necklace.

These are epithets lifted from a tenth-century anthology of poetry and artistic prose by the literary connoisseur Abu Mansur al-Tha’alibi—a privileged arbiter of what counted as the era’s innermost heart. Determined to immortalise the remarkable cultural efflorescence of his contemporary Arab-Islamic world, al-Tha’alibi took upon himself the task of gleaning the anecdotes, biographies, epigrams, and panegyrics he deemed exemplary of his epoch: “sift[ing] our enormous rubbish heaps for our tiny pearls”, as Virginia Woolf once wrote.

Not for nothing did al-Tha’alibi name his compilation Yatimat al-Dahr fi Mahasin Ahl al’-Asr: “The Unique Pearl Concerning the Elegant Achievements of Contemporary People.” From the inheritance of this opulent work, the Tunisian writer Hassouna Mosbahi drew inspiration for his own dazzling, shape-shifting novel Yatim al-Dahr—cleverly rendered in English by William Maynard Hutchins as Solitaire. Hutchins contextualises the title in his helpful preface, explaining that “yatimat” refers to both a “unique, precious pearl” and “fate’s orphan.” “Solitaire” reflects these prismatic valences.

Solitaire, also, is a game one plays with oneself; Mosbahi’s book, in many ways, is a puzzle with no straightforward answers. It is encyclopaedic and uneven and oblique. Stories proliferate, nestled within other stories, structurally echoing the classic Thousand and One Nights.

On a first reading, it is easy to sink into the sediment of the novel’s non-linear chronology, before being pulled abruptly out of the seductive illusion and back onto the newly destabilised present. Mosbahi’s work dissolves temporal barriers, saturating the present with echoes of the past. It feels vertiginous to remember that all the action spans a single day, kaleidoscoped through the mind of the eponymous orphan-protagonist Yunus and taking place mostly along the coast, at the threshold of sea and sand. Language arrives on the page like slips of paper curled up in glass bottles: Sufi prayers, journal entries, newspaper articles, quotations of verse, orally transmitted tales, autobiographical monologues—shored up in their rawness. Digressions expand, often without warning, to constitute entire chapters. Hutchins’ translation captures these tonal shifts impeccably. READ MORE…