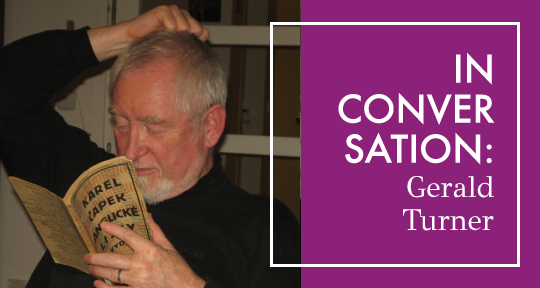

Gerald Turner started translating works by banned Czech authors in the 1980s, a period evoked in vivid detail by one of the leading dissidents and publisher of samizdat in A Czech Dreambook. An inverted roman à clef, this work by Ludvík Vaculík is “a unique mixture of diary, dream journal, and outright fiction—in which the author, his family, his mistresses, the secret police, and leading figures of the Czech underground play major roles.” While in London in February 2020 to launch A Czech Dreambook at the Free Word Centre, Gerald Turner, who is now based in the Czech Republic, talked to Julia Sherwood, Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Slovakia, about grappling with Vaculík’s unique, earthy style and his formidable new project, Jaroslav Hašek’s comic masterpiece The Good Soldier Švejk.

Julia Sherwood (JS): You have been described as Václav Havel’s “court translator”: that is quite an accolade.

Gerald Turner (GS): I haven’t translated any of Havel’s plays but it’s a fair description as I worked closely with him during the last term of his presidency. I translated his articles for the international press and I was translating his correspondence, as well as video messages to various conferences and meetings around the world. In a sense, I was his private translator in this period.

JS: Your most recent translation, of Ludvík Vaculík’s A Czech Dreambook, appeared in 2019, although you completed it much earlier. When did you start working on the translation?

GT: I translated the first excerpt around 1987. Over the years, I spent a lot of time working on it—whenever I had a spare moment, I would take the manuscript out and by the time it was published, I had reworked it many, many times, honing and tweaking it.

JS: Why do you think that, despite the great delay in publication, it is still relevant and has something to say to Anglophone readers?

GT: As for the book’s relevance, Václav Havel certainly believed that it spoke to people around the world. In the conclusion to his essay on the Dreambook, “Responsibility and Fate,” he says:

“With this book Prague sends an important message to the world, one that concerns not just itself and the Czech lands but whose meaning also transcends the present. Will people abroad understand the message and its meaning? Will they understand it straight away? Will they understand it in time? Or will they understand it when it is too late?”

To me, A Czech Dreambook is a great piece of authentic writing and the passage of time should have no effect on it whatsoever.

Jonathan Bolton, the academic who wrote the afterword, sees it more in historical terms, as a portrayal of the politics of the time. Havel, by contrast, regarded it as “a great novel about modern life in general and the crisis of contemporary humanity, as well as about the heroism and tragedy of a man trying to challenge this general crisis.” I believe that the political aspect was secondary, and this is borne out by the fact that after 1989, when Vaculík had a chance to get involved in politics, he turned it down. And the greatest moments in the novel are, as Havel rightly says, his observations on what is happening to the planet, to the environment. READ MORE…