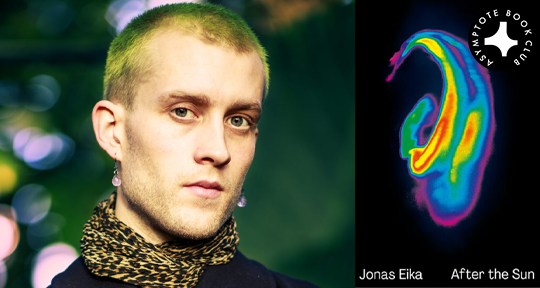

Jonas Eika’s After the Sun is a masterfully realised work of contemporary fiction. In potent combination of the lyrical and the visceral, the five stories that make up the collection span landscapes, relationships, and planes of reality, moving with intensity and poeticism to form characters and worlds which convince us of their reality through their strangeness. After the Sun was featured as our Book Club selection for the month of August, and Blog Editor Xiao Yue Shan spoke live to Jonas Eika and translator Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg about the exceptional qualities of this text—its dream logic, its musicality, and its radicalism. Their conversation is as follows.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): I had approached this collection from the underlying cohesion of dream logic—which seemed to me to be what rounded out all the narratives in this volume. So I was wondering—first of all—do you remember your dreams?

Jonas Eika (JE): I’m really bad at remembering my dreams. I used to be kind of good, but I lost it. One dream that I do remember—which is also relevant to this book—is the end scene of one of the stories called “Rachel, Nevada”, which is in the middle of the book. It ends with this old woman coming home from a concert in this very ecstatic state, telling her husband that the singer from the concert had and came to her and said, So good to see you. We’ve met before, we’ve met on the radio. And that dream is what sort of started the story—I just knew I wanted to find a way to get there, to find out what came before. But I must admit, it’s also rare for me that I use dreams so specifically in writing, or maybe it’s there without me knowing.

Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg (SNH): Actually, I often remember them. But I think my dreams are usually very easily interpretable. I’ve had a dreamscape that’s mapped onto every place that I’ve lived, which is interesting. So I have a Copenhagen scape, and a New York scape—slightly altered landscapes of the places. I grew up on Long Island and in the Long Island scape, there are wolves everywhere—though I’ve never seen a wolf on Long Island. I tend to remember dreams really vividly, actually, and then they kind of dissipate over the course of the day. But the scapes I remember.

XYS: There’s always these associations of dreams with the divine or the primordial, but what actually what related these narratives to dreams for me was the idea that anything could happen at any time, and no matter what was happening at whatever time, it always kind of made sense. There was this cohesion throughout the writing that allowed absurdities to occur without them seeming as absurdities. I mean, this might be just a cultivation of the stories’ surreal circumstances, but I also think it has a lot to do with the innate musicality and the structure of the writing. So I wanted to ask both of you—was this an intentional thing that you were constructing? Or is it something that was more of a stream-of-consciousness ideal?

JE: I really like that description—and I think that the dream logic you talked about is making sense for me now. One of the things I did attempt consciously while writing was to keep it very open in terms of genre and narrative, but with the scenes that seem to break most with the reality of the story, I wanted them to somehow come out of the same logic, or be born out of the same landscape—out of the same objects and emotions that are already in the realist world of the story. So I’m glad you think it feels sort of logical or that it makes sense, even though it’s surprising. And how that came about was actually by finding this musicality in the language. I feel like often when writing works for me, it is like I’m tapping into an underlying rhythm. I will usually have a few sentences, which are often the first sentences of the story that just play around in my mind, and then I really get into that rhythm, and then I start writing when I’m ready or when an energy has sort of build up. So there was something improvisational about it.

SNH: Maybe it’s the dream logic, or the musicality, that ties all of the stories together—because I do think it’s interesting that they are so different. They take place in different places, they have different tones, they’re shifting in perspective, they’re playing with different genres, but there still is something that makes it such a coherent work. Perhaps that does have to do with that specific kind of musicality, that maybe is also in its own way, connected to a logic—or this dream logic.

XYS: I’m always pleasantly surprised when I read prose writers who also kind of have this insistence on continuity of music in their work; we tend to think of fiction as a lattice built architecturally, and then ornaments placed on top of that, but there’s something attractive about the idea that prose writers are paying equal attention to the movement of one sentence to the next—as poets do. Do either of you read or write poetry at all?

JE: Maybe I write a poem now and then, and just hide it in my drawer quickly. But I do read a lot of poetry and I just came to think of the Japanese poet Hiromi Ito, who I really read while writing this book, actually. And, I mean, she writes poetry, but a lot of narrative poetry. I read mostly Wild Grass by the Riverbank, and there’s something about the way she used rhythm and repetition to make even the weirdest things—the scenes where the distinction between life and death or human and non-human totally dissolve—make total sense, because she introduces it by the same patterns and rhythms that constitutes the universe of those poems. So I do read a lot of poetry, and I take that into my prose writing as well.

SNH: One of my guilty pleasures is reading poetry really fast—reading it as if it was prose, because I love that feeling of just being completely overwhelmed by language. And sometimes I’ll go back and read it more slowly, but I think that also has something to do with the way that I translate—a sort of expectation of having this full sensory experience wash over you without thinking too much about it, just letting the craft that’s been put into it do its work. READ MORE…