In this three-part series, Asymptote has asked the 2023 PEN/Heim grantees to talk about their work in progress; their responses, brimming with excitement, conviction, and connection, are a testament to how much translators put themselves into their labor. Through the varied approaches and languages, they share the important commonality of surety: that the work they’ve been entrusted with has an immense potential to illuminate our reality, enlarge our world, and enrich our experiences of literature.

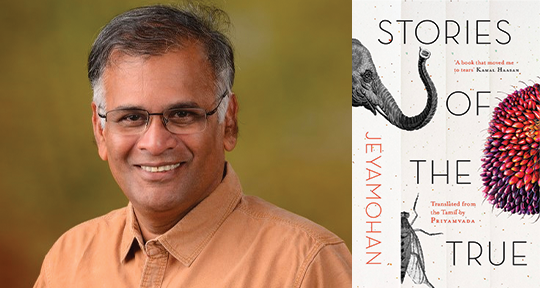

For this final instalment, Margaret Litvin is moved by the living mind behind the words; Priyamvada Ramkumar renders a vivid polyphony of suffering and survival; and co-translators Noor Habib and Zara Khadeeja Majoka work together on poems that both gather and transcend meaning.

Margaret Litvin on Khalil Alrez:

At first it was the rhythm of his sentences: polished and wry, leisurely but not ornamented, like no Arabic prose style I had seen. Next it was the Russianisms: what were all these references to Chekhov, Turgenev, and Bondarchuk doing in contemporary Damascus, as if tailor-made for my research on the literary legacies of Arab-Soviet ties? Finally, it was the personality of Syrian novelist Khalil Alrez himself, glimpsed through every gleaming line. Who else could write such a lovable and quirky novel while escaping from bombed-out Damascus suburbs through Turkey and Greece, eventually completing it in a refugee shelter in Brussels? Who else, well aware of Russia’s role in the war, would set that novel in a fictional zoo run by a Russian former journalist named Victor Ivanitch, and furnish it with a wall newspaper, two wolves, three eagles, a hyena, an Afghan hound, and her friend the poodle Moustache? Khalil and I spoke over Zoom, and for a while I told myself I was just asking questions, not preparing to translate the book. But who was I kidding? The Russian Quarter had captivated me; I needed to share it.

Keeping the Syrian civil war in the background for most of the novel, The Russian Quarter reads nothing like a news dispatch. The action stays close to the unnamed narrator and his Russian-speaking girlfriend Nonna, who live in a rooftop room inside the zoo, next to rebel-held Ghouta. The book’s moral center is a giraffe. Time plays Proustian games, uncoiling spirals of memory. The virtuosic opening paragraph sets up the tension between the narrator’s mounting anxiety (his girlfriend is late in a war zone) and his cool descriptive eye:

On the roof of the zoo in the Russian Quarter, my 14-inch television, balanced on its table near the giraffe’s snout, was showing an archival soccer match between Spain and Uruguay. The rumble of nearby mortar fire had not stopped since early morning; my tea had gone cold waiting for the apple fritters baked by Denis Petrovitch, the clarinet teacher at the Higher Institute of Music, as I sprawled next to the giraffe watching tiny black-and-white goals filmed in Madrid fifty years ago. The artillery was shelling neighboring Ghouta from the orchards of the Russian Quarter. But my ears were trained on the long, still-empty staircase behind the couch on which I lay, expecting it to fill with the sound of Nonna’s elegant footsteps at any moment. She had gone to the cultural center in downtown Damascus to visit her dad. The full moon shone on me, and the screen’s silver light reflected brightly in the giraffe’s wide black eyes and flowed over her thick-fuzzed lips, which nearly touched the long-vanished players, the long-vanished spectators, and the long-vanished grass of the soccer pitch. READ MORE…