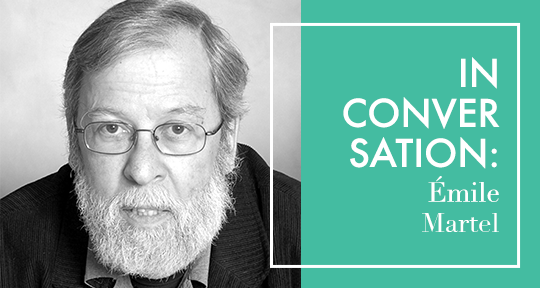

Earlier this year, Sheela Mahadevan had the honour of meeting award-winning Canadian writer and translator Émile Martel in Montréal. In this interview, he provides fascinating insights into his multilingual experiences, the creativity involved in literary translation, and the intersections between translation and creative writing. He also describes the unique experience of familial and collaborative translation in the process of translating the much lauded Life of Pi, written by his son Yann Martel, into French.

Sheela Mahadevan (SM): Émile, you live in Montréal, a city in which code-switching between French and English is commonplace, and you have spent your career writing between various languages: French, English, and Spanish. Could you say a little about your relationship to all these languages, and why you employ French as your literary language?

Émile Martel (EM): Several thousands of us here in Québec are descendants of the first French colonists who came to this region at the start of the seventeenth century. Our collective identity has always been linked to the fact that we speak French; along with the Catholic religion, this is the bond which has enabled us to survive, especially after the English conquest in the middle of the eighteenth century.

I believe that French is the most bountiful of all languages, for it always faithfully provides me with the words I need to describe a particular emotion, object, or location. And I find it musical when it is read aloud. I don’t think I’ve ever begun composing a literary text in English or Spanish spontaneously and unconsciously; not only would my vocabulary be more limited, but I’d feel like I was translating.

My relationship with Spanish is that of an adopted child. When I came to learn Spanish, I was already somewhat competent in English, but I really wanted to read the works of Federico García Lorca in the original language. My professors at Laval University fueled my enthusiasm; I was granted a scholarship to study in Madrid from 1960–1961 at the age of nineteen, and I spent that year entirely immersed in the Spanish language.