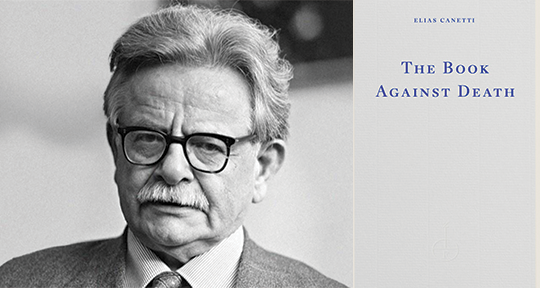

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, translated from the German by Peter Filkins, Fitzcarraldo/New Directions, 2024

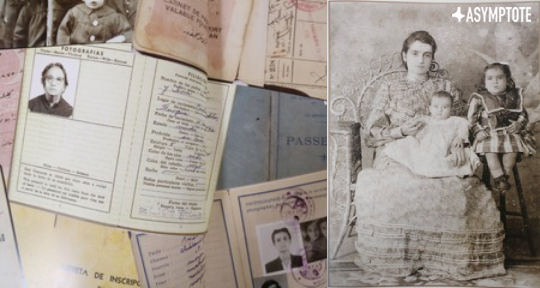

The fact that the twentieth century saw the greatest number of conflict-related deaths in human history might be considered fundamental in explaining the over two-thousand pages Elias Canetti wrote in preparation for his book against death. However, reading the abridged version—published by Fitzcarraldo (UK) and New Directions (US)—one will find that Canetti would object strenuously to this causal explanation. This relation between factuality and literature, Canetti would say, concedes far too much to death in two ways. Firstly, it allows death quantity: by remarking on the sheer numbers, we suggest that the tragedy of death is quantifiable; that the more death there is, the greater the tragedy. Secondly, it allows death quality: by remarking on the specific kind of death—those caused by conflict—we suggest that its calamity is measured in part by the nature of the dying. To Canetti, a lone Don Quixote who ceaselessly struggled for life in a century of death, all death is singular and its tragedy is infinite. In order to better understand this, we must turn to one death: his mother’s.

June 15, 1942

Five years ago today my mother died. Since then my world has turned inside out. To me it is as if it happened just yesterday. Have I really lived five years, and she knows nothing of it? I want to undo each screw of her coffin’s lid with my lips and haul her out. . . I need to find every person whom she knew. I need to retrieve every word she ever said. I need to walk in her steps and smell the flowers she smelled, the great-grandchild of every blossom that she held up to her powerful nostrils. I need to piece back together the mirrors that once reflected her image. I want to know every syllable she could have possibly said in any language.