This month, we’re delighted to present eleven titles from eleven countries, including a lyrical litany of dreams from a Nobel laureate, a psychologically thrilling fiction-study of domestic violence and complicity, a rollicking novel on poverty and police repression in a Brazilian favela, a sharp and surrealistic collection that deeply probes the connection between death and poetry, and much, much more. . .

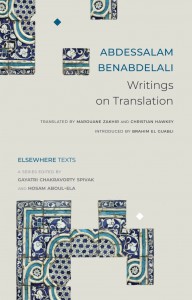

Writings on Translation by Abdessalam Benabdelali, translated from the Arabic by Marouane Zakhir and Christian Hawkey, Seagull Books, 2025

Review by Jordan Silversmith

“What is at stake in translation,” Moroccan philosopher Abdessalam Benabdelali writes, “is the strangeness of the other.” In Writings on Translation, a slim but resonant volume translated with clarity and philosophical sensitivity by Marouane Zakhir and Christian Hawkey, Benabdelali argues not only that translation is foundational to the development of Arabic and European thought, but that it constitutes a mode of ethical relation—a hosting of the stranger.

Composed of essays selected from two earlier Arabic-language works, this collection positions translation not as the failed transfer of meaning between stable tongues, but as a generative rupture in the myth of linguistic purity. Echoing Derrida and drawing on classical Arabic poetics, Benabdelali deftly critiques the nationalist drive to see language as a closed identity. “The instrument of translation is a living language,” he writes, “and its mirror is condemned to be broken.” It is in this shattering that thought is permitted to migrate.

What emerges then is a meditation on translation as both inheritance and resistance. Benabdelali revisits the Abbasid-era Bayt al-Hikma, critiques 18th-century French Orientalism, and confronts the ambivalence of Arabic literary modernity, where some authors write in expectation of translation while others fear its erasure. His essays resist binary framings of colonizer and colonized, instead advocating for a polyglossic hospitality in which meaning is always provisional and always in motion. READ MORE…