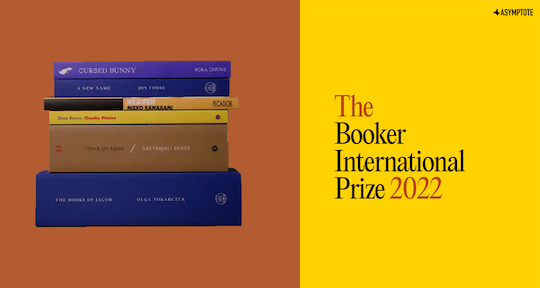

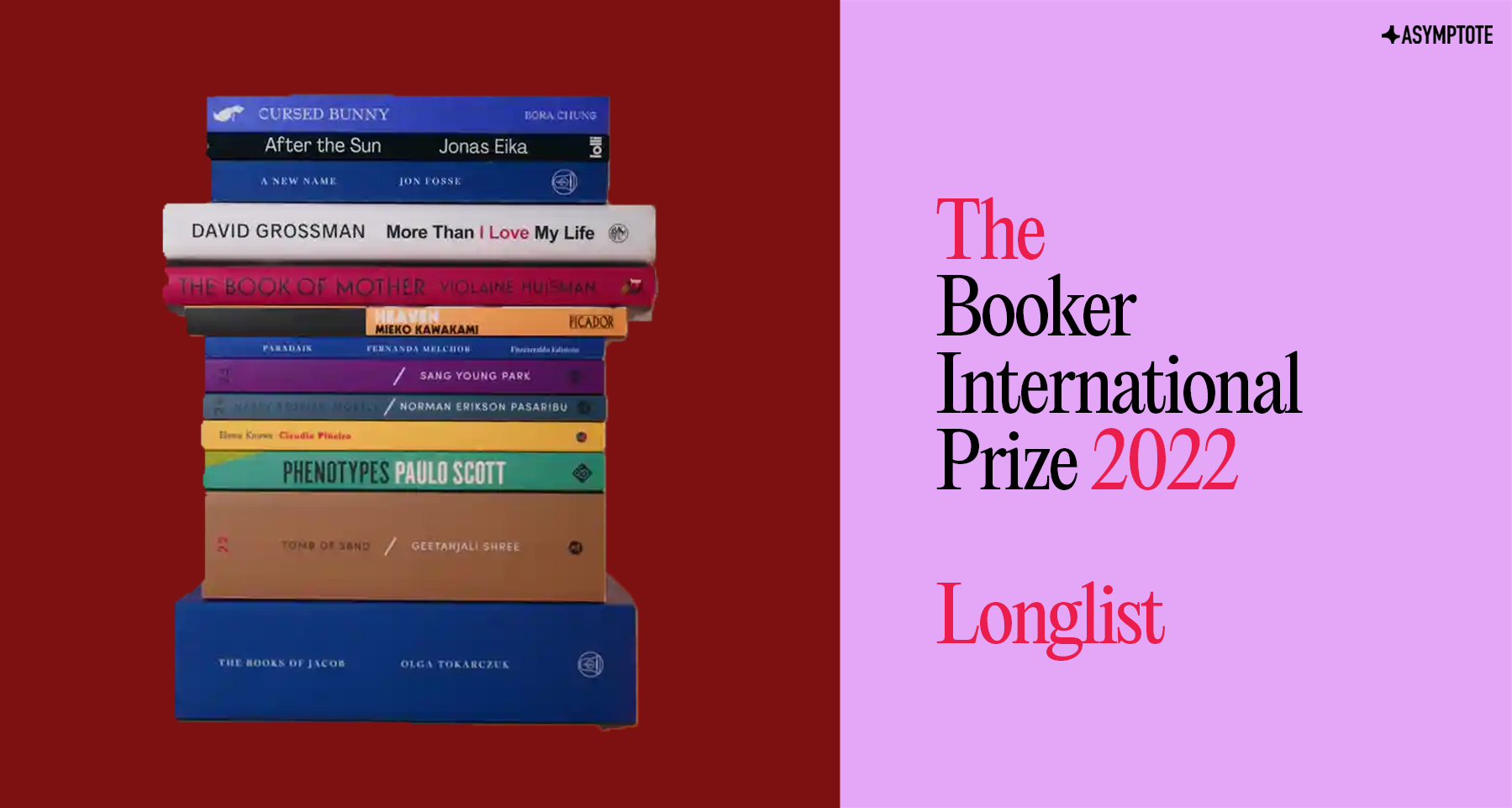

As we countdown to the 2022 Booker International Prize announcement on May 26, the contenders for the award offer new indications and perspectives by which to think about the world of literature and translation. In the following essay, our resident Booker expert Barbara Halla considers the digressive and variegated realm of “women’s writing”—that five out of the six titles on the shortlist were works by women authors is both evidence of the work’s scope and diversity, and also an overwhelming rejection of that old and tired idea: that women’s writing is simply of any gender-specific experience.

Since 2019, I have been relentlessly punished by the memory of this essay by an Albanian critic who argued in favor of the inherent superiority of men’s writing. His reasoning went like this: men write to triumph over life, whereas women write to survive. And for that very reason, the author claimed, men’s literature has universal appeal, as men are able to overcome the limitations of their own lived experiences and perspectives, while women’s writing focuses only on their painfully limited (i.e., domestic) existence.

My frustration with this article was compounded by finding its logic replicated elsewhere, in other books about the history of women in literature, and even during a conversation with another Albanian male writer a few months after reading that article. In the ensuing Q&A, the writer in question issued a complacent mea culpa about his lack of interest in women writers—he simply found their writing too limited and introspective. Of course, this is understandable. After all, it is easier to relate to Tolstoy’s Prince Andrei or Goethe’s Faust when one spends their days in the battlefield before making a deal with the devil and are whisked away for a night of debauchery with witches. After all, this is what “real” life is actually about, and it’s not like men ever write about minor concerns like marriage or childcare.

I’m being facetious, but this understanding of literature is pernicious—this desire to determine artistic value along essentialist gender lines. It also seeks to explain the existence of global and local literary canons as meritocratic, rather than the result of conscious policy decisions that have contributed to the erasure and devaluing of women’s writing. I was wondering about this argument as I made my way through the six books shortlisted for the Booker International 2022—five of which were written by women and published in the past fifteen years in South Korea, India, Poland, and Argentina. To be straightforward to the point of being trite: these five books undermine the notion that there is anything akin to a universal “women’s writing.” READ MORE…